| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

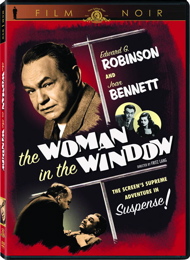

The Woman in the Window |

|

The Woman in the Window MGM / Fox 1944 / B&W / 1:37 flat full frame / 99 min. / Street Date July 10, 2007 / 19.98 Starring Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett, Raymond Massey, Dan Duryea Cinematography Milton Krasner Art Direction Duncan Cramer Film Editors Gene Fowler Jr., Marjorie Fowler Original Music Arthur Lange Written by Nunnally Johnson from a novel by J.H. Wallis Produced by Nunnally Johnson Directed by Fritz Lang |

Considered a top noir and one of Fritz Lang's very best American films, The Woman in the Window is a dreamlike meditation on crime and guilt, distilled to its essence by screenwriter and producer Nunnally Johnson. Lang's clean and simple graphic sense amplifies the story's sense of oneiric clarity. Yielding briefly to temptation, a saintly professor quickly finds himself caught in a maelstrom of crime and murder.

The Woman in the Window was so successful that Lang and his stars Joan Bennett and Dan Duryea came back the next year with the somewhat similar Scarlet Street, and even darker and creepier tale of a meek man destroyed by his secret inner needs. This earlier film is still considered Lang's most pure investigation of the nature of guilt and conscience.

The words Sigmund Freud are written on Prof. Wanley's blackboard as he explains that culpability in murder is a relative concept. The then says a rather platonic goodbye to his wife and kids at the train station, just in Billy Wilder's later comedy The Seven-Year Itch. Perhaps inspired by a reading of Solomon's Song of Songs Wanley stops to stare at the beautiful portrait, and his fantasy of middle-aged adventure comes to life. The flesh and blood Alice Reed finds him interesting and invites him first for a drink and then to her apartment, to see more pictures of her.

It's all too good to resist, and too good to be real. Alice's angry lover Claude Mazard (Arthur Loft) bursts in, and in a few seconds is on the floor, stabbed to death. Wanley decides that he doesn't want to throw his life away and agrees to dispose of the body. But Alice retains his monogrammed pen as insurance, and Wanley doesn't realize that his best friend, the D.A. Frank Lalor (Raymond Massey) will find so much evidence when the body is discovered out in the country (by a chubby Boy Scout, seen in a Fury- like newsreel). Everything Wanley does seems to point to a psychological desire to be arrested. He acts guilty in front of two policemen and a tollgate clerk, and practically flaunts the idea that he's a possible crime suspect in front of Lalor and the detective. Lalor even jokes that Wanley is trying to be caught. The D.A. notes at least five clues linking Wanley to the scene of the crime, but never thinks to connect them. An important plot point eventually explains why all of these psychological ideas are operating on the surface of the film, but revealing it would be a terrible spoiler, so we won't dig further. Nunnally Johnson and Fritz Lang use logic and cause-and-effect to sketch out complications that slowly convince Wanley that his fate has taken an unexplainable, fatalistic turn. The murdered man has an unscrupulous bodyguard named Heidt (Dan Duryea, in his second noir role), who immediately blackmails Alice for money and sexual favors. Wanley gives Alice $5,000 in a vain attempt to silence Heidt, but blackmailers never know when enough's enough. Perhaps an overdose of Wanley's sleeping pills will do the job ....

Not since Peter Ibbetson had a movie so beautifully described a dream state. From the moment that Wanley meets Alice, his life becomes a dream. The professor had idly spoken to his friends of his wistful idylls of sexual adventure and he's clearly inspired by the beautiful erotic poetry of the Biblical Song of Songs. He's a sweet soul uninterested in the burlesque houses that even the stuffy D.A. finds amusing. Wanley considers himself middle-aged and broken-down, and not attracted to his wife even though he loves her. Alice appears as almost a hallucination, and is unaccountably attracted to the pleasant but far from handsome Wanley. For Wanley, she's a clear case of wish fulfillment. We immediately suspect that Alice is luring him to her flat -- to see her 'etchings', no less. Yet she remains true to Wanley in that she doesn't try to blackmail him. As Wanley never sees the malicious Heidt, he has only the information from Lalor that he actually exists.

Fritz Lang's American crime films became increasingly less ornate, and not simply because their budgets were low. The scripts zeroed in on a finite set of characters and didn't worry too much about backgrounds or realism. Although only a late title like Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is truly minimalist, even the studio-bound The Woman in the Window carefully controls every person on screen and every setting. Modern viewers may not think Wanley is guilty of anything more than staying late at a woman's apartment and drinking champagne, but in this universe, forbidden desires are as compromising as forbidden acts. A seemingly predetermined web draws Wanley toward shame, dishonor and death -- the fatalistic noir trap at the center of this classic femme fatale tale.

Lang pulls off a clever transition in The Woman in the Window that became part of its word-of-mouth. It's so well done that we cannot see exactly where the switcheroo takes place: you'll understand when you see it. In interviews Lang talked about a breakaway wardrobe trick, but we don't see the change take place. Is there a dissolve somewhere in the shot, or a split screen? I'm no longer sure.

Robinson is terrific as the kindly Wanley, a switch from his extroverted Keyes in Double Indemnity which came out earlier in the year and apparently opened the Production Code doors to screen stories of sordid domestic murders. The Woman in the Window is able to cheat a bit with the code, by avoiding a direct violation ... but explaining would be risking another spoiler.

Joan Bennett is appropriately dreamy as Wanley's unattainable sex object. For the next year's Scarlet Street she'd add a nasty streak to the character. Dan Duryea's crude slimeball rifles through Alice's lingerie drawers and hiding places as a substitute for simply raping her; we're quickly convinced that killing him would be a great idea. Unlike Alfred Hitchcock, Fritz Lang does not mock us for finding vicarious thrills in the murders. He's more interested in colder intellectual traps.

MGM's The Woman in the Window will look like eyewash to the noir fan accustomed to 5th-generation graymarket dupes; Milton Krasner's rich cinematography adds new levels of detail and allows us to analyze Lang's effects in depth. For instance, a crucial meeting between Alice and Heidt plays out in front of a mirror that doubles the images as in Scarlet Street, an effect that Lang would never create accidentally.

The sound is also clear and free of the hiss that previously masked the faint choral effect heard at the appearances of Ms. Bennett. The feature has alternate tracks in French and Spanish and subtitles in English and Spanish. But no extras appear, which is a true shame. Many another minor noir has benefited greatly from a good commentary (noir commentaries tend to be very illuminating) and The Woman in the Window has a million points worthy of discussion. For starters, Professor Wanley finds his dream girl by literally window shopping ... Alice Reed shows up almost like a pricey commodity, ready for purchase.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

The Woman in the Window rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: none

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: July 7, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |