|

|

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

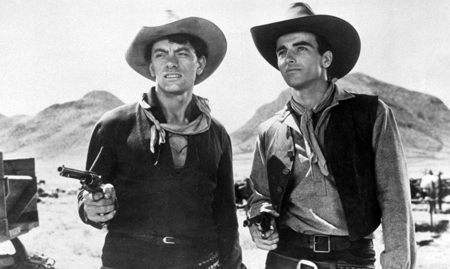

One can't get any closer to the center of the western genre than Howard Hawks' 1948 Red River, a film so good that practically everyone likes it. It's one of the first film appearances of Montgomery Clift, who never again played a western hero. It's the picture where John Wayne showed that he could hold his own on a screen with any other actor. Borden Chase's primal story of a cattle drive still compels despite Chase's low opinion of Charles Schnee's contribution to the shooting script. Hawks produced the film for United Artists release, gambling that his instincts would deliver another hit, and earn profit for him instead of one of the studio moguls. Hawks had a bit of a rough go getting Red River into the theaters - a story that led to two versions of the movie contending for place of primacy.

Borden Chase's tale is almost a multi-generational saga in the vein of Edna Ferber. In search of a future on a ranch of his own, ambitious & charismatic Thomas Dunson leaves his love-struck girlfriend Fen (Coleen Gray) behind on a wagon train, and with his sidekick Nadine Groot (Walter Brennan) uses force to take a huge plot of Texas border land away from a Mexican landlord. He 'adopts' orphan Matt Garth (as an adult, Montgomery Clift), who becomes a deadly gunfighter and goes to fight in the Civil War. Defeat finds Dunson with a lot of cattle and no local market in Texas, so in desperation he rounds up all the steers he can find for a risky trail drive to Missouri. But Dunson has problems running his outfit. He soon threatens to kill, and then kills, cowboys that try to quit the drive. The more reasonable Matt defies his boss / father figure when he takes the herd away from Dunson, promising to deliver it to a rumored new rail-head at Abilene, Kansas. The furious Dunson promises in return to catch up with Matt and kill him.

Red River gives us characters so vivid that they became archetypes for a decade's worth of westerns to follow. There's Walter Brennan's Groot, a cantankerous chuck wagon jockey who loses his false teeth in a poker game, and can only borrow them back for meals. There's Cherry Valance, a narcissistic gunfighter who engages in a 'friendly' quick-draw competition with Matt. The rest of the cowboys on the drive are a thick slice of western types, interesting men that Hawks arrays in 'stand and watch' compositions with ten or twelve distinct personalities in the frame. They form yet another Hawks 'professional unit' that appeals to male viewers, a gregarious association of mutual respect. For over two hours we watch 'real men' doing a 'real job': Hawks spent weeks on location driving 1500 steers up hills and across rivers.

As western film authority Robert S. Birchard used to maintain, inspired direction in Red River transcends a patchy script. There are only two women in this predominantly male show. Coleen Gray's Fen carries such a powerful sexual charge that her aura hangs over the whole picture, and is not even touched by the late introduction of Joanne Dru's character. Dru's "Tess Milay" is a terrible 'author's construction,' a woman who verbalizes (constantly, redundantly, annoyingly) all the character tensions between Dunson and Matthew that shouldn't need verbalizing. Dru's Milay makes a mockery of the final showdown. Resolving the film's heavy-duty father/son conflict through the intervention of a dame in screwball comedy mode is not Howard Hawks' best idea. Although the ending is funny, the jolting tonal shift makes Red River finish like a TV sitcom. It's as if Lucille Ball intervened between Ahab and Moby Dick, arguing that their big-deal feud doesn't amount to a hill of blubber in this crazy world. Red River is so good that this miscalculation doesn't cripple the experience. We concede that Borden Chase's elegiac, unnecessarily morbid original ending sounds far less appealing. As for Joanne Dru, she has one of the best "tough babe" moments in all of Hawks, courtesy of a convincing stage illusion with an Indian arrow.

Red River introduces a slippery time-lapse trick that was a big source of amusement in film school, where we students thought we were experts in the analysis of cinematic flashbacks and time-shift gimmicks. Dunson talks to fourteen year-old Matt Garth, explaining how in just ten years he plans to build his two cows into a big cattle empire. As Dunson talks we see the growing ranch, the new buildings and corrals, etc. When he's finished, Matt is suddenly ten years older and Dunson has gray sideburns. "Well, here we are ten years later", he whines, "and we have more damn cows than you can shake a stick at. Now we gotta take 'em to Missouri." 1

If only life were like that. Following the unwritten rule that a flashback or flash-forward should always return the film to the "real" present tense, it would be amusing to have Dunson finish talking as the image dissolves back to the three of them back where they started, standing around their wagon with two cows and the dead vaquero Dunson just shot. Dunson stares a bit and then throws a dirt clod down, as would a deadpan Bill Murray. "Yep, that's what we gotta do alright. Maybe."

Borden Chase used the exact same construction in Anthony Mann's Bend of the River, with a settler explaining how his new community will be established before winter comes. Hawks himself re-used the device in a movie that's essentially a remake of Red River in ancient Egypt, 1955's Land of the Pharaohs. The head architect explains how the great piddamid pyramid of Cheops will be built and we see a montage of its construction, as ten years telescopes into four minutes. Meanwhile, young Dewey Martin grows to manhood, just as did Montgomery Clift.

Red River has a bona fide classic moment every ten minutes or so, from the yip-yip-yahoo launch of the cattle drive, to the stampede caused by 'sweet tooth Bunk Kenneally', to Tom Dunson's murders of his own men, committed with the dubious justification that the leader of a cattle drive is akin to a captain at sea. Then there's the rescue of a wagon train of gamblers and entertainers, and the happy arrival in Abiliene, greeted by the 19th century's symbol of business success, a mighty steam engine. Composer Dimitri Tiomkin had assembled a rather crazy, psychologically jumbled Big Western music score for David O. Selznick's earlier Duel in the Sun. Tiomkin's music for Red River is arguably his first iconic "Big Sky" western opera. Tiomkin's work would soon define the '50s western, pushing an ambitious, aggressive All-American vibe. That's pretty impressive for a musician born in the Ukraine more than twenty years before the Russian Revolution.

Howard Hawks' filming style never looked better, with single close-ups reserved only for very privileged moments. Hawks' unity of time makes scenes fold into each other perfectly. A lot is happening, but we're never given a chance to become restless. Coming out of the ten-year time jump, the discussion of economics, the meeting with the other rancher, and the competition between Matthew Garth and Cherry Valance are all really one unbroken scene. Despite its postwar psychological angle, the emotional message imparted is, to coin a phrase, as positive and robust as the great outdoors itself. Red River is a tough act to follow, one of Howard Hawks' very best films and one of the great American movies.

The Criterion Collection's Dual-Format Blu-ray + DVD of Red River is a marvelous deluxe presentation. Two versions of the film are encoded on two Blu-rays and two DVD discs. The B&W show is literally one beautiful Russell Harlan shot after another. Criterion has brushed up MGM's well-preserved long version of the movie, which is referred to here as the preview version.

The long version is the one that has survived in tip-top shape, unlike many another film favorite including Hawks' own sublime The Big Sky. We had heard early rumors that Peter Bogdanovich, who knew Hawks as a close friend, might insist that Criterion only use a shorter cut referred to here as the theatrical version. Bogdanovich's concise and rational video piece puts our worries to rest. The theatrical version lops about six minutes out of the movie. It tightens the pace, introducing new opticals to hurry some transitions. The frequent 'diary entry' milestone graphics are replaced by Walter Brennan's voice, conveying the same information in words. To these eyes it seems clear that Hawks was trimming the film down to make it more 'exhibition friendly', to allow time for more showings per day, or a second feature. Booking films in 1949 wasn't easy for small distributors like United Artists, as the majors controlled the majority of the country's theaters.

The theatrical version also changes the final scene, dropping some of the suspenseful musical accompaniment to Dunson's march into Abilene and editing out quite a bit of dynamic "showdown business" before he fires his gun.

As it turns out, the theatrical cut is not what Howard Hawks wanted, either. Peter Bogdanovich explains that Howard Hughes sued because this final scene was too similar to the finish of Hughes' earlier The Outlaw. Editorial changes were negotiated. That's why the superbly directed lead-in to the final confrontation is so mangled in the theatrical cut. Bogdanovich says that the real cut of Red River should be the theatrical, with the ending from the preview version. I say let's forget about the theatrical version altogether. To me it looks like Hawks chopped his movie up in the fear that it would flop and he'd never see a profit. Perhaps United Artists advised him to shorten the film, or else. The preview cut plays beautifully and also looks much better. But blessings upon Mr. Bogdanovich for his honest explanation of the versions. 2

Red River came to TV in both versions. Long before I read that two distinct cuts existed, I wondered why I was misremembering details in the show. The long version is preferable in every way. There's enough Walter Brennan geezer-speak in the movie itself, making his extra narration too much of a good thing. Did Hawks decide that his audience of school kids couldn't read? The constant editorial tightening also mucks up the pleasing rhythms of Hawks' direction. The long cut allows a shot to play every once in a while, accompanied only by music. I also like the 'ride to the rescue' cutting in the wagon train sequence, which has a string of artificial 'hero' medium close-ups of the cowboys riding and shooting. For a brief second these wonderful shots bring back the 'ride 'em cowboy' spirit of serial westerns. The theatrical version skips all of this, and further up-cuts rush us into the next dialogue exchange.

That's only one extra on this packed disc set. Boganovich's taped interview with Hawks is fascinating, as is my old professor Jim Kitses' excellent interview with writer Borden Chase, whose work easily dominated class-act '50s westerns. Molly Haskell's take on Red River comes across well in her interview. A broader overview of the western genre is seen in Lee Clark Mitchell's interview piece.

Back in the realm of standard extras, we have a radio adaptation of the movie, a trailer and a booklet with a Geoffrey O'Brien essay and Ric Gentry's text interview with Hawks' trusted editor Christian Nyby. Nyby lets slip that the ending was reshot, which is interesting -- wasn't it staged on location? Nyby also says that a detail in that confrontation is still missing, where Dunson shoots off part of Matt's hat -- and part of his ear as well.

Topping things off is a fat paperback edition of Borden Chase's source novel, Blazing Guns on the Chisolm Trail. Criterion's disc producer Curtis Tsui has brought this herd to market in fine shape. Even with all these discs and extras, the western is still being sold at Criterion's standard price point.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Red River Blu-ray + DVD

rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Two versions -- theatrical and pre-release/standard TV version; interviews with Peter Bogdanovich, Lee Clark Mitchell and Molly Haskell; audio conversation twixt Bogdanovich and director Howard Hawks, audio interview with western authority Jim Kitses and Borden Chase; radio adaptation, trailer; booklet with essay by Geoffrey O'Brien and interview with Christian Nyby; paperback of Borden Chase's source novel Blazing Guns on the Chisolm Trail.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly?

YES; Subtitles: English

Packaging: Two Blu-rays and two DVDs in folding card and plastic disc holder with booklet and paper back book in card sleeve.

Reviewed: May 14, 2014

Republished by permission of Turner Classic Movies.

Footnote:

1. What? You mean that's not an accurate dialogue quote?

Return

2. Most people first saw the complete preview cut of Red River when it showed on TV, and slowly supplanted 16mm prints of the shorter theatrical version. It's very likely that the Red River you know, is the preview version presented here as an alternate cut. The other time I think this exact same thing happened is with Frank Capra's It's a Wonderful Life. That film's 'final' wide release version was a cut-down that trimmed away two major sections. UCLA's first 35mm prints were shortened in this way. But the 16mm prints circulated to TV (when not cut by TV stations) were full-length. The restoration of Capra's film involved a lot of work by UCLA and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, while the 'restoration' of Red River just came down to the choice of a printing element. And how marvelous it is that element was prime-quality film source.

Return

Text © Copyright 2014 Glenn Erickson

See more exclusive reviews on the Savant Main Page.

The version of this review on the Savant main site has additional images, footnotes and credits information, and may be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Return to Top of Page

|