| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volumes One and Two

The Criterion Collection // Unrated // May 25, 2010

List Price: $79.95 [Buy now and save at Amazon]

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

To a point, I feel as if I've failed. My familiarity with Stan Brakhage was limited largely to his reputation: the name more closely associated with experimental film than any other and a man responsible for producing several hundred of them over the course of nearly a half-century. Like most anyone who'd taken a film class at one time or another, I'd seen Brakhage's Mothlight, but those few minutes represented the entirety of my direct knowledge of his work. My true introduction to Brakhage came through this Blu-ray release of fifty-six of his many films, and I'll admit that a review of such a sprawling, challenging collection with a deadline bearing down is far from an ideal way to first experience his work.

Brakhage had an appreciation for traditional dramatic narrative but didn't feel that it represented art...didn't believe there had been any new ground broken on that front since the time of the Greeks, let alone since the dawn of cinema. Brakhage tested the outermost boundaries of what film is capable of producing. Using the medium to advance his concept of "moving visual thinking", the imagery in Brakhage's work is often shapeless...nameless. You aren't meant to recognize or immediately, consciously comprehend what's being splashed across the screen...it's there to evoke a certain emotion. Inspired by the pioneering work of Sergei Eisenstein, Brakhage also explored the concept of montage -- cutting between multiple images that combine into a single truth -- and further built upon this foundation by superimposing layers of images on top of one another. Frequently throughout this collection, Brakhage doesn't give the viewer the opportunity to fully process an image at first glance; propelled by the rhythm of his visual poetry, the filmmaker is ready to move onto the next image at times within a fraction of a second, well before the

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

There is no longer a comfortable point of reference. There is no clearly structured narrative. There is no dialogue and rarely any people to speak of in the frame. There are frequently no recognizable shapes, and the overwhelming majority of Brakhage's films are entirely silent. Everything you know is wrong. Brakhage's work demands an entirely new way of seeing...of processing information... and this is why I feel as if I've failed. Brakhage assaults with one barrage of strange and wonderful imagery after another. The visuals are all there is because to Brakhage, all that is, is visual...we're all light. With reviewing comes a deadline, and the uninitiated can't expect to come close to comprehending and appreciating Brakhage in a tightly compressed period of time. Work this challenging and unique demands more than I unfortunately had to offer.

Brakhage's films can be grueling for those without the proper perspective, and I'll confess to being among them. I could marvel at the interplay of light and shadow throughout 1959's Wedlock House: An Intercourse, for instance: a film in which negative footage of Brakhage making love to his wife is intercut with the two of them quarreling...blanketed in darkness. My first time through, though, I couldn't comprehend what I was seeing; nearly the entirety of the frame remained black to best isolate its lovers, and the imagery changed so frantically that my untrained eyes were unable to properly adjust. It's difficult viewing, and this is one of the more accessible films in the entire collection. The Act of Seeing with one's own eyes is a half-hour of graphic autopsy footage, reflecting Brakhage's obsession with death as men in white smocks carve apart the remains of the dead as a butcher would a side of beef. The deeply influential Window Water Baby Moving does not flinch at any point, documenting in perhaps uncomfortably graphic detail the birth of Brakhage's first child, alternating between tender

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

I've been writing reviews and criticism for eleven years now, and never have I felt as ill-prepared as I do here. I could marvel at the striking use of light throughout Duplicity III, the gorgeous photography and fascination with the sun in Star Garden, and the most breathtaking of Brakhage's painted films, "..." Reel Five and the three-part Persian Series. Still, I struggled desperately to make sense of what I was seeing, but it was somewhat of a futile effort. The sensory...the emotional response outweighs critical thought when it comes to Brakhage. I failed to realize this until it was too late. My true fascination with Brakhage didn't begin until I started to explore the many hours of extras throughout this boxed set. A remarkably engaging speaker, Brakhage's passion proved to be infectious. Rewatching some of his films with my mind better aligned, I found that I had a far greater appreciation for them, and I only wish I had the time to experience more of them again before writing this review.

I couldn't be more impressed with the spectacular work that Criterion has invested into this collection of Brakhage's work. There's nothing the least bit accessible or commercial about it, and yet it's immediately apparent that no effort has been spared in the assembly of this set. I'd venture that a very large percentage of those reading this review will find Brakhage's films incredibly difficult to watch. As much as I admire and respect what Brakhage accomplished throughout his long and prolific career, I'm still uncertain about how I feel about it as well; my mind is too deeply rooted in the conventional. That's rather not the point, though. These are significant and deeply influential works of art, and the care and consideration lavished upon Brakhage's films is nothing short of exceptional, even by the already dizzyingly high standards of the Criterion Collection. Though I wouldn't blindly recommend By Brakhage to the uninitiated due to the extraordinarily challenging nature of the material, this colossal effort is nonetheless well-deserving of DVD Talk's highest recommendation. DVD Talk Collectors' Series.

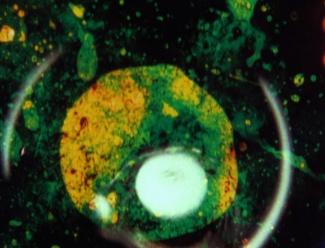

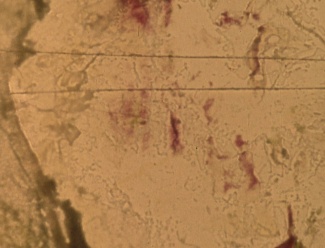

Video

The expected goal with a Blu-ray release is perfection. Stan Brakhage, on the other hand, enjoyed the sense that his films were crafted by a man...that the imagery splashed across the screen is celluloid once touched by human hands...that it wasn't an invisible process achieved by whirring gears, distant chemicals, or digital sorcery. This high definition release of more than fifty of Brakhage's films reflects this. Clumsy splices are left intact. Negative dust that had been burned into every print of one film or another has not been removed. Speckling and assorted wear are

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

Not having had the opportunity to watch the films featured throughout By Brakhage on DVD, I can't comment on how this Blu-ray release compares. The nature of the material certainly doesn't lend itself to a traditional high definition experience, of course. Nearly all of these films were captured on whatever 16mm stock Brakhage could get his hands on, and a handful of 8mm films are featured throughout the second half of the collection. The photography can be rather soft and grainy, and with as frantically as the imagery changes, whatever fine detail it offers can be difficult to resolve. The difference is certainly there, though. The grain structure is at times strikingly tight and well-defined, such as in the first two black-and-white films and Visions in Meditation. There are undoubtedly moments when I feel as if the level of detail before me is more than DVD as a format is capable of reproducing. The most vivid explosions of colors throughout Brakhage's painted films too suggest something more robust than I'd expect to see in standard definition. Without the ability to a direct comparison, I wouldn't think that this would be an altogether startling improvement over Criterion's DVD release...that the difference would be perhaps slighter than most but still noticeable.

Criterion sets out to strike a flawless balance between authenticity and perfection, and this is reflected in their release of By Brakhage. I'm sure it goes without saying that a 56-year-old film shot on gun camera stock from WWII isn't going to rival the high definition experience of Watchmen, or that a 16mm experiment originated by applying moth wings and grass to strips of tape doesn't take advantage of a $4,000 television in quite the same way as Avatar. These are still visually striking films, however, mirroring Brakhage's original intent and no doubt his preferences for their presentation.

With one exception, all of Brakhage's films are presented on Blu-ray at their original aspect ratio of 1.37:1 or so. Chinese Series, the last film in the set and the lone widescreen entry, is windowboxed to 1.85:1. Each film has been encoded with AVC, and these three discs take full advantage of the capacity a BD-50 has to offer. Brakhage's films are no doubt nightmarish to compress, with each frame of much of his work being entirely different than the last, but the expansive capacity of these dual-layer Blu-ray discs coupled with Criterion's skilled craftsmanship ensures that this is never a concern. I did notice some blocking in particularly dark moments throughout The Dead when I was assembling the screen captures for this review, but I could not see them from a traditional viewing distance on my home theater.

Audio

Stan Brakhage believed the rhythm of his visual poetry would only be disrupted by the addition of sound. It follows then that of the fifty-six films in this collection, only nine have an accompanying soundtrack. The overwhelming majority are entirely silent. (It may be worth noting that Scenes from Under Childhood, Section One is presented both ways, reflecting Brakhage's mixed feelings in this particular case.)

The flipside of the package states that uncompressed audio is offered for those few films with a soundtrack. As best I can tell, this is incorrect. Criterion hasn't provided PCM audio but a set of Dolby Digital soundtracks encoded at a bitrate of 192kbps. I'd expect that the difference would be negligible, though. The fidelity of the original audio tends to be rather limited, and there's no shortage of hiss or crackling throughout a number of them. The music featured in Desistfilm is deliberately harsh and distorted, and the few minimalist scores of the films that follow don't cry out for the expansive sound of a lossless soundtrack. Despite the limited bitrate, however, the jagged, stabbing piano keys throughout "..." Reel Five -- the lone stereo audio in this otherwise silent or monaural collection -- sound terrific. Overall, this collection of Brakhage's films makes very sparing use of sound, but when it does, it's effective, despite the lack of lossless or uncompressed audio that likely wouldn't have amounted to much of a difference regardless.

No alternate soundtracks or subtitles have been provided, but due to the nature of the material, neither are necessary.

Extras

This

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

Disc One

The first disc in the set offers four 'Brakhage on Brakhage' conversations, each running approximately nine minutes. In the first, Brakhage reads from decades-old writings of his before refuting the concept of "chance operations" as it applies to himself and such artists as Jackson Pollack and John Cage. He goes onto explain the origin of his trademark scratched titles and the importance of the rhythm of the project...of conveying a sense of the surface of the film itself. We are also given the opportunity to see all of the strips of film that comprise his shortest work, the nine second Eye Myth.Disc Two

'Brakhage on Brakhage II' is the first of Brakhage's explorations into the concept of "moving visual thinking" in this boxed set. He speaks of the gulf between what his own physical eyes can perceive versus his mind's eye. Also discussed here are Brakhage's disinterest in video as opposed to experiencing films in a proper theater, his correspondances with various poets, and how he appreciates mainstream cinema but doesn't believe it warrants the sort of thought and consideration it so often receives.

The third 'Brakhage on Brakhage' turns its focus largely to the camera as an instrument, particularly the filmmaker's embrace of 8mm after his 16mm equipment was stolen. Brakhage marvels at the effectiveness of the even smaller, more lightweight 8mm camera in capturing daily life...in beating with the pulse of the person holding it...in empowering Brakhage, as he puts it, to be a "writer of movement". Brakhage also delves into the sort of trance state he'd fall into during the production of his films, one in which his actions are better described as reflexive rather than deliberate.

Finally, 'Brakhage on Brakhage IV' explores the topics that most deeply fascinate the filmmaker: birth, sex, death, and the search for God. Brakhage shows off a framed strip of 70mm film that went unused in The Dante Quartet, likens his willingness to abandon extravagance and return to basics to that of Whistler's painted cigar box tops, and his self-diagnosis that his painting of film strips would ultimately be responsible for the virulent form of bladder cancer that so deeply ravaged his body.

Brakhage doesn't offer audio commentary for his films, but nineteen of the twenty-six works showcased in this first volume are accompanied by remarks that serve much the same function. There are 49 minutes' worth of these remarks, recorded between 1996 and 2002. While discussing Desistfilm, for instance, Brakhage delves into his cinematic influences, noting the same fascination with French surrealism and Italian neo-realism that shaped the work of Fellini while also making apparent the impact Eisenstein's concept of montage had. Brakhage does a marvelous job exploring the backdrop that led him to filmmaking, challenging the notion that film was inaccessible to artists. We learn aboutthe feature-length Dog Star Man as an attempt to produce a visual epic, one that features the "inner cellular dreams" that would suggest to the Woodman what was to come in the day that follows. Brakhage's comments on Window Water Baby Moving put the drive to capture childbirth in context and the enormous hurdles that had to be overcome to have a home delivery to document at all. An audio commentary for the nine second Eye Myth would've been challenging, to say the least, and these remarks give Brakhage the opportunity to discuss the film at slightly more length. Among the many, many other highlights are Brakhage discussing the world creation myths he'd invent every night that would go on to shape The Stars are Beautiful, the intrusion of sound and the possible negative influence of a title on his visual poetry in The Wold-Shadow, how it's to The Dante Quartet's benefit that Brakhage's grand mixed format ambitions didn't quite come to pass, Delicacies of Molten Horror Synapse marking the first of Brakhage's mentions of hypnagogic vision in this collection, Mothlight drawing inspiration from Brakhage's struggles as a filmmaker feeling so much like a moth flying into a candle and becoming consumed by its flames, and bleakly laughing at how Commingled Containers would've been a marvelous final statement if indeed he'd died on the operating table the day after it was filmed.

[click on the thumbnail to enlarge]

Brakhage held weekly salons in which he'd screen -- and at times debut -- films by himself and other artists he admired, and this would be followed by a group discussion. Three excerpts from these salons, recorded between 1993 and 2002, have been included as part of this collection. With 23rd Psalm Branch, Brakhage notes the profound impact that Freud had on his life, particularly the concept that the most ordinary, mundane moments we experience day in and day out can be so charged in the proper context that they resound with meaning. He explores the often unrecognized darker side of being a child in Scenes from Under Childhood, Section One, while still trying to be fair and include the sense of awe and adventure that's also an integral part of childhood. Finally, Brakhage notes the three day fit of rage and horror following a matricidal nightmare that inspired Murder Psalm.Disc Three

Brakhage is featured again in a 37 minute interview conducted in 1990, and the emphasis is predominantly on the philosophies of the artist; I don't believe Brakhage once mentions a single of his films by name. Brakhage debates the concept of the artist serving as a litmus for society, discusses The Muse as a very real entity rather than an intangible concept, and explores the spiritual truth of the visually abstract. Brakhage doesn't overinflate his own skill or importance, noting that he fails in every film he's made to some extent. From there, Brakhage addresses whether or not he's evolved as an artist and touches on ceasing his photography of his own life.

The last of the extras on this second disc is a fifty minute lecture from 1996, presented here without any accompanying video. It's here that Brakhage's concepts of moving visual thinking...of hypnagogic vision...are most thoroughly explored. His comments address the arts as a whole -- a medium for the private person to be exposed and to erupt in public as he can in no other form -- and how he believes film can one day be an art itself as far off on the horizon though that may be. Brakhage describes himself as a midwife for whatever cinematic impulses come through his nervous system and that his greatest achievement is simply survivng, especially in a climate this hostile towards the arts. Many of Brakhage's philosophies are explored in detail here: drawing inspiration from music though he prefers that his films be silent, painting offering a way to present that which cannot be photographed, the many challenges inherent to meticulously painting directly on a negative, the nature of collaboration, and his fascination with the purity of a fetus' dreams. Brakhage is an endlessly fascinating speaker, and part of this is owed to a marvelous sense of humor, smirking at the idea that the public can't stomach abstract art but will watch the O.J. Simpson car chase for hours on end when it's nothing more than one tiny box slowly being followed by four other boxes.

An additional pair ofexcerpts from Brakhage's salon discussions are featured here as well. In Boulder Blues and Pearls and..., Brakhage notes how he wanted to stay true to his presentation of the city of Boulder, pointing out some of the specific landmarks featured in his film and how he attempted to compose with that which might be caught in people's peripheral vision. Again, his sense of humor is appreciated, noting that Boulder is one of the few cities on these shores in which the sight a coffin in someone's yard doesn't seem the least bit out of place. Afterwards, Brakhage discusses how The Cat of the Worm's Green Realm is an entirely visual story, one that would be as gripping as reading text from a book but without ever spelling out what the premise is, exactly.

[click on the thumbnail to enlarge]

Three more 'Brakhage on Brakhage' conversations are offered on this disc, running just over twenty minutes in total. Among the topics here are the many eccentricities of Joseph Cornell that Brakhage was subjected to when tasked to film The Wonder Ring, debating the semantics of such terms as "experimental film", "underground", and "avant-garde", the infinite possibilities of painting on film, and Brakhage's incorporation of chemotherapy and his surgeries into the filmmaking process.

Another lecture from 1996 has been included with this disc, but intriguingly, Brakhage mentions his own films only in passing. The lecture does begin by charting the early years of his career and the plays he staged in San Francisco, but the subject is ultimately not himself but Gertrude Stein, who Brakhage argues is the greatest writer of the 20th Century. This lecture serves at least in part as a biography of Stein, charting her life and movements as well as the influence this had on her work. Despite Brakhage's deep admiration for Stein, so impressed with her exacting use of language in which changing one word unravels all that follows, he's unabashedly critical of her lesser works. The inclusion of this lecture seems entirely appropriate: Brakhage's discussion largely centers on how Stein pushed the English language to its outermost extremes, and the filmmaker does much the same with the concept of film in his own work. Brakhage also discusses his dissatisfaction with the word "abstract" when applied to his films, though he doesn't argue the point when it's directed towards him, and he again notes how drama is the least changing of all the arts.

The last of the extras is Marilyn Brakhage's For Stan, a sixteen minute collection of footage of her husband working on Visions in Meditation in 1988. Shot on film, this is the only of the extras to be transferred and presented in 1080p24, and appropriate given its subject, For Stan is silent.

Packaged inside By Brakhage is a nearly hundred page booklet penned by those closet to Brakhage and his work. Illustrated with strips of films and series of superimpositions, we learn more about the process in selecting the fifty-six works featured here from a body of some 350, a spectacular introduction to Brakhage's mindset and creative process, and detailed notes about the hurdles associated with the preservation of such challenging films.

The Final Word

It's impossible not

|

| [click on the thumbnail to enlarge] |

Brakhage's films exist in a realm beyond convention. There is no narrative nor any traditionally rendered characters to latch onto here. The imagery is elliptical as it is, and it changes so frantically that there's often only the tiniest fraction of a second to process what's being splashed across the screen. Quite a number of these films were produced without the aid of a camera, and the overwhelming majority of this nearly eleven hour collection has no accompanying sound. I say this only as fair warning. For the uninitiated, which I'll confess to being myself, exploring this collection can be a grueling experience. Brakhage challenges traditional conventions, and for those of us whose only point of reference is, more or less, the conventional, many of these films can be very difficult to watch. It's an experience that's ultimately rewarding, however. I feel as if I have a much greater appreciation for the language of cinema now than I did a week ago, and especially after devouring the some five hours of extras in this collection, I'm eager to watch these films of Brakhage's again with more informed eyes.

By Brakhage is not the sort of collection I'd blindly recommend. I'll admit that I'm still processing much of what I'd watched, and given the deeply challenging nature of the material, those unfamiliar with Brakhage's work may wish to seek out this collection as a rental or explore some of his films online before deciding on a purchase. By any measure, however, By Brakhage is an extraordinary and startlingly thorough cross-section of many dozens of Stan Brakhage's most seminal works, and it's bolstered further by an exceptional selection of extras to put these films in a more readily appreciated context. Despite its inaccessibility, the significance...the passion and consideration...the sheer enormity of the time and effort that clearly went into realizing this collection cannot possibly be met with anything less than DVD Talk's highest recommendation. DVD Talk Collectors' Series.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||