| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

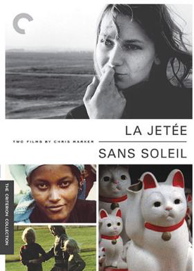

La Jetée / Sans Soleil |

|

La Jetée / Sans Soleil Criterion 387 1962 / 1983 / B&W & Color / 1:78 anamorphic widescreen / 27 & 103 min. / Street Date June 26, 2007 / 39.95 Directed by Chris Marker |

Intellectually oriented art filmmakers have their own idols, and one most revered by his peers is the enigmatic Chris Marker. While maintaining an aura of personal secrecy, Marker has by turns investigated poetry, filmmaking, novels, photography and multimedia work. Criterion's release of two of Marker's most influential films, La Jetée and Sans soleil offers a weighty package for our perusal. Every film student eventually discovers that movies can be more complicated than simply 'blurring the line between fantasy and reality.' Higher up the brain chain we have the movies of Alain Resnais that plumb the concepts of memory and obsession by altering the cinematic form itself. Somewhere beyond are the supremely intelligent films of Chris Marker. His minimalist La Jetée encompasses an entire subgenre of Science Fiction while making the elaborate Last Year at Marienbad seem like it's working too hard. Resnais was so blown away by La Jetée that he suggested that the elusive Chris Marker must be an alien!

The 1963 La Jetée is a fast-moving B&W Science Fiction time travel tale composed of still images, sound effects and a calm narration. Post-apocalyptic Parisians are confined underground to avoid radiation. Scientists have found a way to send a man back in time by honing his ability to concentrate on a single event in the past. Our hero (Davis Hanich) remembers a fleeting glimpse of the face of a woman (Hélène Chatelain) from an airport viewing platform where a man was shot to death, just before the nuclear war. Blindfolded and wired to a monitoring device, the hero is drugged to facilitate his 'entry' into his own memories, where he accosts the woman and falls in love with her. They visit a museum of natural history where 'memories' of extinct animals are kept. The grainy, evocative stills depict their relationship, and the screen turns to live action for just a second or two. The hero uses his newfound skill to go into the future, where the survivors of humanity are eager to help. But he insists on returning to the fateful day on the airport observation platform ...

Although the concept doubtlessly pre-existed in a multitude of stories from H.G. Wells, Luis Borges, Philip K. Dick and Ambrose Bierce, the story is most familiar from low grade Sci-Fi films like the 1958 Terror from the Year 5000 where researchers use a time chamber to trade artifacts with future humans. Marker also expresses the 'time paradox' concept that began with 'The Silent Man' in Wells' The Time Machine and figures in most time travel stories right up through the Back to the Future movies. Marker's film is truly influential. Alain Resnais' 1968 J'taime, j'taime concerns another lovesick time traveler 'remembering' his way into the past to prevent a long-ago tragedy. Brian DePalma's Obsession is also about a man desperate to change his past, and concludes with a similar extended dash across an airport lounge to face an unexpected fate. In the somewhat lazy Somewhere in Time, Richard Matheson's lover needs only to dream to meet his lover in a bygone age. The trite Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind invents an entire memory-managing technology just to help two lovers sort out their petty differences. The beauty of La Jetée is its simplicity. Everything is clear; the complex concept unfolds for the viewer in perfect harmony.

Pop surreal romanticism blooms in a film like Portrait of Jennie, where a painter's need for a muse is all that is required to defy time and space. La Jetée's acknowledged inspiration is Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, another tale of a man forcing reality to bend to his romantic will, and inadvertently repeating a cycle of tragedy. The time traveler is much like moviegoer Marker, who wishes to return to the 'reality' of a film to make love to its heroine.

The link between Chris Marker and Vertigo is cemented in his 1983 Sans soleil, a deceptive documentary that at first seems a ramble of images from Japan, Africa and other countries. The narration purports to be the text of a cameraman's letters, which begin with random observations but soon are deep into philosophical thoughts about ... well, about most everything. The film announces its free-form nature by opening with a shot of three Icelandic children walking down a road, while the disembodied narrator wonders where it will fit in the film.

Sans soleil is neither glib nor flip. "Memory is not the opposite of forgetting but its lining" is a potent mouthful that requires some thought. Using his twice-removed author's voice (the reading of a fictitious cameraman's letters), Marker constantly questions the nature of truth on film, wondering at the meaning of the looks that random Africans give his staring camera lens. His ideas about travel and foreign cultures ignore notions of good taste without stooping to the Mondo Cane level of exploitation: we see Japanese exhibits of strange phallic statuary and a weird museum where stuffed wild animals copulate in graphic detail. He also borrows footage from other films, like those shots of Iceland and a disturbing sequence covering the killing of a graceful giraffe by high-powered rifle. Fountains of blood spurt from the animal's wounds before it crashes to the ground.

Most of Marker's themes defy easy explanation -- the film is probably their clearest expression. The movie finishes in San Francisco with Marker's attempt to return to Vertigo by tracing its key filming locations. The associations between recorded film and human memory pile up, with the idea that for many of us, un-lived film fantasies are more real and obsessive than anything that happens in our lives. That may be the price of living with an (illusory?) intellectual consciousness. It's too bad that Marker didn't make a film called My Dinner with Kim Novak, but then again, he's exploring the phenomenon of abstracted obsessions, not the real experience.

Sans soleil showcases the video images of Hayao Yamaneko, solarized feedback distortions that seem to represent memories scattered or partially dissolved in the mind. Electronically rendered dream imagery found expression in psychedelic light shows but is best used in Wim Wenders' 1991 Until the End of the World where it expresses the very Chris Marker concept of decayed memories pulled from the brain. When a person is exposed to these intimate psychic mementos, they almost immediately become obsessed ...

Criterion's DVD of La Jetée and Sans soleil are in flawless condition. I've seen poor copies of La Jetée and one fairly good release on an early DVD 'magazine' of artistic films (Short Cinema Journal), but the enhanced B&W transfer here is the first that allows one to savor Marker's foto-roman handiwork at its full effect.

Jean-Pierre Gorin appears in interviews on both titles. For La Jetée his speaking topics are scattered across a menu page, like the bits of memory-reality to be orchestrated in Spielberg's Minority Report. Video featurettes and excerpts examine Marker and compare his films to Vertigo and a David Bowie music video -- with the added irony being that for an early stage persona Bowie took the identity of an alien from another world. Disc producer Kim Hendrickson must have had a stiff task finding good extras, but the fat insert booklet contains a masterful essay by Catherine Lupton, as well as a collection of intriguing notes and mini-essays by Chris Marker himself.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

La Jetée / Sans Soleil rates:

Movie: Both Excellent

Video: Both Excellent

Sound: Both Excellent

Supplements: Interviews with Jean-Pierre Gorin, Chris Darke's short film Chris on Chris, French TV show excerpts on David Bowie music video, and Hitchcock's Vertigo; booklet essay by Catherine Lupton, interview with Marker, filmmaking notes by Marker

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: July 9, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |