| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

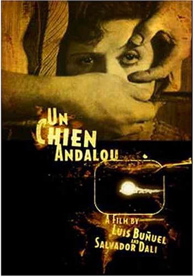

Un chien Andalou

|

||||

Luis Buñuel's Un chien andalou (An Andalusian Dog) is the key surrealist film from the 1920s, a masterpiece of promotion as much as it is a milestone in cinematic art. Filmmaker Luis Buñuel teamed with the painter Salvador Dalí to drop an artistic hand grenade into the bourgeois culture, and guaranteed the continuation of surrealism as one of the strongest art movements of the century. The impish Buñuel takes the central ideas of the Surrealist Manifesto to heart. The seventeen-minute film is purposely anarchic, shockingly impudent and willfully irrational. Rejecting the notion that art leads us calmly to a humanistic set of ideals, Un chien andalou opens with a razor-wielding man (Buñuel himself) observing a thin cloud 'slicing' across the face of the moon. The man then turns his razor on a young woman with staring eyes. The rest of the film continues with strange and often indefinable symbolic scenes and events. An odd man in the street rides a bicycle; he wears various aprons and frills associated with Catholic priests. He carries a striped box, which later becomes a repository for a severed hand. A concerned crowd gathers when the odd man falls onto the curb, but nobody pays attention when a young woman is run over a few moments later. The film was reportedly collected from dreams remembered by Buñuel and Dalí, and images like a nest of ants living in the palm of a man's hand come straight from the famous artist. Sex is a major theme. As a libidinous young man rubs the breasts of a young woman, we dissolve from her clothed to her naked, and then to the man fondling her buttocks instead. A comic pursuit has disturbing moments, as when the man's mouth disappears, to be replaced by the woman's armpit hair! As if making fun of symbolism for its own sake, Buñuel shows the man struggling to pull two ropes across the room. The ropes are attached to two priests, who calmly allow themselves to be dragged across the floor. They in turn are tied to a pair of grand pianos, each with a dead, bleeding mule lying on top! Other mysterious visuals are linked to nature. A sea urchin is associated with a woman's armpit, and we see Buñuel's first obsessive screen image of an insect, none other than a death's head moth. The professed reason for the shocks is to shake up bourgeois sensibilities, undercutting the viewer's attachment to the givens of film in predigested commercial cinema. Buñuel would continue to explore the surreal for much of the rest of his career, as if in search of an elusive truth behind the 'false' respectability of civilized values. Although the film begs for interpretation it should be first acknowledged as purposeful provocation without object: just by disturbing us, Buñuel has done his job. Much of what passes for surreal influence can be seen in Buñuel's images. Actions are displaced from their 'appropriate' emotions, and vice-versa. A man dies longing for love, and as he reaches for the object of his desire, a matched cut places him in a grassy field, touching the naked back of a woman as he falls. Titles nonsensically reject cause and effect: "EIGHT YEARS LATER"; "SIXTEEN YEARS EARLIER." The little bits of melodrama that peek through the choppy continuity remind of the early surrealists' proposed pattern of proper film-going. André Breton claimed that he and his friends would go to a movie district, enter a picture in the middle, stay only a short while, and then rush to the next theater. The result was a surreal accident, a series of cinematic effects liberated from narrative logic. 1 It can be argued that simple film flashbacks often achieve this kind of narrative dislocation, at least until the story rights itself again. Oddball pictures like The Locket nest flashbacks inside flashbacks, effectively re-creating the old novels (like the one on which The Saragossa Manuscript is based) that helped inspire surrealism in the first place. Buster Keaton's crazy film tricks in Sherlock Jr. are at heart part of the surreal experience, as is much of the anarchic comedy of The Marx Brothers. 2 I've only seen one really good print of Un chien andalou. Transflux Films' DVD copy is better than many but still not particularly distinguished. The film is intact but the framing is tight on the top, and the contrast is rather high. Some shots momentarily wash out to white, harming dissolves and occasionally making it difficult to identify details ... Had I not already been aware of the 'dead mules on the pianos' scene, I'm not certain I'd know what I was looking at. The print on view has a soundtrack of tangos and Wagner (Tristan und Isolde: Liebestod) that was synchronized with the film in 1960. Author Stephen Barber contributes a careful commentary, quoting liberally from important surrealist writings. He gets to the heart of Un chien andalou by relating it to the initial concept of film as a conduit to pure ideas, before movies became entertainment. Exclusive to Transflux's DVD are two interviews with Buñuel's son Juan-Luis, who speaks perfect American English. Juan-Luis begins by talking about the director's background in a tiny Spanish town. He gives a good account of the process by which his father would develop dream images into potent filmic scenes. He describes the film's premiere and the violent reactionary reception given Buñuel's next film, L'Age d'Or. Juan-Luis's later stories of Buñuel in Hollywood and New York are also very interesting. The second intereview is about Luis Buñuel's rocky relationship with Salvador Dalí. A text extra called Mystery of Cinema is an abridged transcript of a speech Buñuel gave in 1953.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Un chien Andalou rates:

Footnotes:

1. It's easy to do this now. Bored cable TV watchers do it all the time, just by clicking through channels sampling and searching for interesting content. By flipping between a few soap operas playing at the same time, one can create all kinds of 'accidental' harmonies.

2. Even the vaguely subversive TV cartoon show The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle has a subversive streak, challenging basic ideas about politics and reality. One of the show's commercial break bumpers shows Bullwinkle the Moose and Rocket J. Squirrel sprouting from the ground like plants, along with the rest of a patch of sunflowers ... looking remarkably similar to the final image of Un chien andalou.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |