| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

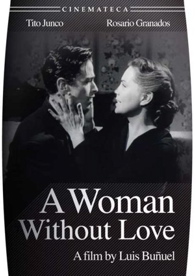

A Woman Without Love |

|

A Woman Without Love Facets/Cinemateca 1951 / B&W / 1:37 flat full frame / 85 min. / Una mujer sin amor / Street Date September 25, 2007 / 24.95 Starring Rosario Granados, Tito Junco, Julio Villarreal, Joaqu�n Cordero, Javier Loyá Cinematography Raú Martinez Solares Production Design Gunther Gerzso Film Editor Jorge Bustos Original Music Raúl Lavista Written by Luis Buñuel, Jaime Salvador, Rodolfo Usigli from a novel by Guy de Maupassant Produced by Sergio Kogan Directed by Luis Buñuel |

Luis Buñuel has been quoted as calling his 1951 A Woman without Love (Una mujer sin amor) his worst film, which can be taken as a warning never to trust film directors when they assess their own work. Following Buñuel's celebrated Los Olvidados, the resolutely non-surrealistic soap opera was surely a conceptual step backward for the Spanish director working in exile in Mexico. The story adapts a novel by Guy de Maupassant to serve as a vehicle for a female star. In Buñuel's more celebrated fantasies, we're accustomed to seeing his subversive subtext leap to the forefront. The disturbing undercurrent in A Woman without Love is the whole concept. Not quite a straight soap opera, the film is a stealthy examination of the institutions of marriage and motherhood, and social compact that requires women to sacrifice themselves to the demands of others.

If the heroine of A Woman without Love really thought about her predicament, she might re-title her tale "The Stifled Cry of the Bourgeois Housewife." Luis Buñuel's critique of society is just as strong here as it is in his more overtly fantastic films. The dictatorial Don Carlos shuts his wife out of man-to-man conversations and locks his presumed-guilty son in a room with the admonition, "Incarceration and hunger would be good for revolutionaries, too." In the very first scene Buñuel shows Don Carlos banishing a customer from his exclusive store for trying to barter down a price. That low-class behavior is for flea markets and peasants.

Rosario is in a prison of imposed obligations. Her parents were poor so she married the wealthy Don Carlos, a man who doesn't respect her. The only love she feels is for her son. The strongest family ties In Latin America are said to be between mothers and sons; daughters leave and husbands lose interest, but a son's love is forever. Rosario hasn't experienced romantic love until her affair with Julio. Don Carlos' sickness brings her back to reality, and her chance for fulfillment goes away.

Twenty years later, it looks as though Rosario will be martyred yet again. Her two sons are feuding over their desire for the same woman (a beautiful female doctor, so presumably not a fortune hunter). The more serious Carlos resents his father for refusing to bankroll his idea for a clinic until young Miguel has graduated. Then Don Carlos lets the plan fall through because it prevents him from a maximum killing in a real estate deal. When Miguel suddenly inherits millions from a family friend he never met, Carlos is furious. The younger, less dedicated brother has the girl, the money and the luck, and Carlos is expected to be quietly grateful for a secondary position in the new clinic. Carlos shares his father's harsh attitude toward women, romancing his head nurse (Eva Calvo) and then snubbing her to her face. Because Miguel follows his heart and has a positive attitude, Carlos thinks him a frivolous playboy.

(spoiler) When the truth comes out about Julio and Rosario, the conflict becomes a matter between mother and sons. Rosario makes a strong verbal defense of her choices in life and asks her sons to consider who besides her has suffered: her love was not shameful, only impossible. The relatively subdued ending is chillingly appropriate.

At this point in his career Luis Buñuel was committed to establishing a commercial career. His assignment in A Woman without Love was to remake an earlier French version, shot for shot if possible. Viewers expecting weird dream sequences and surrealistic visuals are bound to be disappointed, but the show is a solid entry in his filmography. Buñuel sublimates his themes in a way comparable to the melodramas churned out by Douglas Sirk later in the 1950s. Sirk's overheated symbolism and forced dramatics now seem more flamboyant than radical, while Buñuel's little drama simply sets the dilemma of an upper-class Mexican housewife in relief. Is she living her own life, or living in self-denial? If quiet obedience to family obligations is its own reward, why is she resentful?

Rosario Granados (repeating from Luis Buñuel's La gran calavera) does well pretending to be 25, and then 45. In some scenes she looks a bit like a sad Donna Reed, or Jean Brooks of The Seventh Victim. Handsome Tito Junco would return in Buñuel's later The Exterminating Angel. Julio Villareal appeared in many golden-age Mexican movies as well as Buñuel's Gran Casino and Pedro Armendariz's The Torch. Joaquín Cordero was in the director's later El rio y la muerte as well as various Mexican horror classics, such as Orlak, el infierno de Frankenstein.

Facets and Cinemateca's disc of A Woman without Love presents this elusive Luis Buñuel film in a good transfer with clear Spanish audio and English subtitles. It was reviewed from a check disc, making any quality assessment inconclusive. No extras are included. Subtitled versions of the film were once so scarce that critic Raymond Durgnat had to finish his career book on Luis Buñuel without seeing this title. Facets is also releasing Buñuel's El Bruto and the relatively unknown, wickedly subversive Susana. An imprisoned young woman prays to be allowed to avenge herself on the male sex, and is answered by a lightning bolt that blows down the wall of her cell, setting her free.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

A Woman Without Love (Una mujer sin amor) rates:

Movie: Very Good

Video: Good ?

Sound: Very Good

Supplements: None

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: October 8, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |