| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

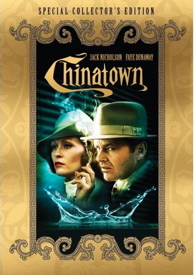

Chinatown |

|

Chinatown Special Collector's Edition Paramount 1974 / Color / 2:35 anamorphic widescreen / 131 min. / Street Date November 6, 2007 / 14.99 Starring Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston, Perry Lopez, John Hillerman, Darrell Zwerling, Diane Ladd, Roy Jenson, Roman Polanski, Richard Bakalyan, Joe Mantell, Bruce Glover, James Hong Cinematography John A. Alonzo Production Design Richard Sylbert Art Direction W. Stewart Campbell Film Editor Sam O'Steen Original Music Jerry Goldsmith Written by Robert Towne Produced by Robert Evans Directed by Roman Polanski |

The American style called Film Noir came to an unofficial end in 1958 with Orson Welles' Touch of Evil. Everything made thereafter is technically a neo-noir. Plenty of 1960s films exhibit aspects of the same style, like Burt Kennedy's 1965 B&W The Money Trap. The James Garner vehicle Marlowe clearly shows the influence even as it pursues other agendas. Along with interesting nostalgia pieces like John Flynn's The Outfit, Roman Polanski's 1974 Chinatown was one of the first films that the UCLA critical studies crowd recognized as a bona fide Neo-Noir.

Writer Robert Towne's drama of 1930s Los Angeles is much more than a look back at old romantic thriller conventions. Following in the footsteps of classic noirs that yearned for lost hopes and ideals, Chinatown constructs a noir metaphor for the Garden of Eden. In this case, the Garden has been overrun by the Devil. The water to make it grow has been stolen by political powers intent on 'owning' the future, in perpetuity.

Chinatown captures the sense of a sick and disillusioned Los Angeles, a sleepy town with big secrets to hide. A private dick in the classic Raymond Chandler tradition, Jake Gittes claims that he's an ethical businessman and even starts a fistfight over his reputation. But Jake also nurses a fatal streak of idealism. He hides it from the man who really knows him, Lieutenant Lou Escobar of the L.A.P.D.. Something happened a number of years ago in Chinatown that resulted in Jake's ignominious departure from the force. All of Jake's snappy dialogue and feigned sophistication can't hide the fact that he's traumatized over the fate of a woman he wanted to protect. Gittes thinks he can redeem himself by not repeating his mistakes with the mysterious, potentially dangerous Evelyn Mulwray. He's smarter now, and has little trouble uncovering Noah Cross's diabolical real estate conspiracy. But Gittes tells the police too many lies and makes critical mistakes. His bigotry is a weakness: he can snap out curses in Chinese, but fumbles a clue offered by a 'jabbering' Japanese gardener. Worse still, Gittes foolishly underestimates his enemy's deadly reach.

They say that only foreigners can really nail the American ambience, and Roman Polanski finds the essence of 1930s Los Angeles on every street corner. For some scenes designer Richard Sylbert had only to drop some television aerials and make sure the curbs were correctly painted. A compact apartment building serving as the home of sometime actress Ida Sessions (Diane Ladd) resembles the Alvarado courtyard address where William Desmond Taylor was murdered. A dry wash and an orange grove represent the San Fernando Valley. Just as 'foretold' in Chinatown, the Valley has now become an endless residential development. Mulwray's Beverly Hills (or Los Feliz) estate, Echo Park, various reservoirs and Avalon Bay haven't substantially changed, but Polanski evokes the past with even better signifiers, like the sight of a boiling radiator through a barbershop window and the chi-chi cars in the valet lot of the Downtown Biltmore. As if acknowledging the jest that L.A. is some kind of unplanned, unconscious urban mistake, a hideaway motel carries the name Macondo, a lift from Gabriel Gárcia Márquez' novel of "realismo mágico", 100 Years of Solitude.

Jack Nicholson was already a movie star but earned full credibility in Chinatown; for the first time we saw his range and felt the full gravity behind his boyish features and short-sighted gaze. Jake Gittes isn't quite as smart as he thinks he is. We don't blame him for not catching all the twists laid before him and he would have done much better if he were less cocky about his ability to snooker people. He tries to snooker Lt. Escobar one time too many.

Jake receives a knightly battle scar in the form of a slit nostril. He wears his bandage proudly, not realizing that the gash is really the Mark of Cain. The nervous, imperious Evelyn Mulwray also has a flaw, a discolored spot in the iris of one of her eyes. The 'flaw' is more than an excuse not to look Jake in the eye. Eye color is hereditary, and Evelyn's psychological disturbance has everything to do with shameful hereditary secrets. Los Angeles is a primitive land where the powerful break taboos, letting succeeding generations deal with the unspeakable consequences.

The cost of idealism and innocence always runs high in Polanski films, and Chinatown is no exception. Jake Gittes is 'nosy', a lesson he's taught with a switchblade knife. The flaw in Evelyn's eye becomes a horrible, perverse punishment.

John Huston's charming monster Noah Cross is the true face behind the powerful 'Big Daddy' cliché. Robert Towne fudges the details and the decade but the designers of Los Angeles did indeed conspire to steal the water supply of a far-off county and then withhold it until the drought-plagued San Fernando Valley was 'under new ownership.' Then the Valley was miraculously incorporated into the City proper, and all that water was suddenly available for agriculture at bargain rates. Cross calls this 'buying the future' but Chinatown compares it to a rape, after which the rapist is allowed to profit from the misery of his victims. Our history books taught us about Father Serra, John Sutter and the gold rush, but Chinatown's message is that the real history can be found swept under the rug.

John Alonzo's wonderful cinematography resurrects the allure of Venetian blinds and also finds beauty in the textured plaster walls of Evelyn's 'Spanish Colonial' house. He evokes an even older California in a brief glimpse of Old Mexico parade riders practicing on Noah Cross's Catalina ranch. Polanski begins the movie with a noir joke: The Academy-ratio sepia-toned main titles float in the center of the Panavision frame, and then dissolve to the film's first color shot, a close-up of a B&W photo.

DVD fans were vocal in their displeasure with Paramount's previous disc of Chinatown. This new enhanced transfer looks much more solid and detailed, with fewer mushy greens. Audio tracks are available in a 5.1 stereo remix, the better to appreciate Jerry Goldsmith's sublime score, with additional original mono mixes in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese. Subtitles are in Eng/Fr/Spanish.

The killer extra is a relaxed, authoritative new Laurent Bouzereau documentary, broken up into four chapters. Jack Nicholson is an enthusiastic participant and producer Robert Evans clearly thinks Chinatown is his best film. Roman Polanski is interviewed in Paris about the 'ordinary job' that turned into one of his favorites. Especially well handled is the dispute between Polanski and author Robert Towne over the film's ending. Towne wanted a finish similar to his beginning, a replay of The Maltese Falcon. Polanski felt the finale needed something even darker. Chinatown follows the Polanski rule that, no matter how badly we think one of his films will end, the ending is even worse.

The Chinatown posters always looked strange, but the disc's cover design is exceptionally ugly.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Chinatown Special Collector's Edition rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Four part Laurent Bouzereau docu, trailer

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: November 6, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |