| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Adult All Male Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk The Blue Room DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Battleship Potemkin |

|

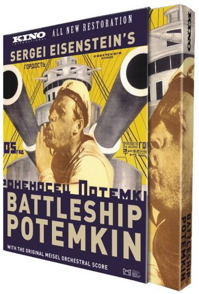

Battleship Potemkin Kino 1925 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 69 min. / Street Date October 23, 2007 / 29.95 Starring Vladimir Barsky, A. Antonov, M. Gomorov, Levchenko, Repnikova, Marusov Cinematography Edward Tissé The "Iron Five" (Eisenstein's assistants) Maxim Shtraukh, M. Gomorov, A Levhsin, A. Antonov, Gregory Alexandrov Art Direction Vasili Rakhals Film Editor Sergei Eisenstein Original Music Edmund Meisel Written by Nina Gadzhanova-Shutko, Sergei Eisenstein Produced by Jakob Bliokh, for the First Studio Goskino, Moskow Directed by Sergei Eisenstein |

Battleship Potemkin is the first Soviet classic most film students were exposed to, and for good reason. It convinced a lot of doubters that cinema was an art form and in terms of film language is arguably the most influential title before Orson Welles' Citizen Kane. Initially embraced more strongly in Germany than in the Soviet Union, Potemkin made the rounds of 1920s film societies and cinema clubs, earning plenty of superlatives. Douglas Fairbanks thought it was the most artistic thing he'd ever seen. A New York reviewer said that although nobody who attended his screening wanted to become a Bolshevik, they found a new belief in the power of movies.

The film put Sergei Eisenstein on the map as the greatest of Soviet filmmakers. Although some of Eisenstein's best-known contemporaries criticized the acting styles employed, all admitted that he'd harnessed the power of montage -- editing images to create a cumulative effect -- as no filmmaker had before. Kino's 2 DVD boxed set of Battleship Potemkin presents the masterpiece in an impressive new restoration with extras that tell the interesting story of a national treasure that underwent forty years of political censorship and revision. Even 'film school' versions shown up until the last few years were censored copies that changed or deleted inter-titles and violent shots. This new copy very closely replicates Eisenstein's original cut.

Synopsis: Conditions are intolerable on board the Prince Potemkin of Taurida, a Czarist battle dreadnaught. When the ship's doctor tells crewmen that the maggots infesting their meat supply are harmless, the men protest. The officers threaten to shoot the mutineers but a firing squad refuses to follow through, and the men riot and take over the ship. The Potemkin pulls into the Black Sea port of Odessa, where a wake is held on shore for the mutiny's spiritual leader, Vakulinchuk (A. Antonov). Huge crowds of sympathetic citizens stand in line to honor the fallen hero, and soon the people of Odessa are contributing foodstuffs. But the rest of the Russian fleet is on its way to punish the mutinous sailors. A thousand well-wishers wave to the Potemkin from the Odessa steps, unaware that Czarist Cossack troops have been dispatched to punish them.

Battleship Potemkin was one of a series of 1925 'festival' films commissioned to celebrate the 1905 uprising, a violent and tragic precursor to Russia's 1917 Revolution. Running out of time, Eisenstein and the group of helpers he called "The Iron Five" dropped plans for an epic about all the events of 1905 and concentrated instead on the Potemkin mutiny. As the original ship had years before been broken up for scrap, a sister ship called The Twelve Apostles served as the filming set. It had been partially dismantled and was being used as storage for old mines. Missing deck sections were carefully rebuilt in plywood, and the ship was pivoted on its mooring to face out into the Black Sea. Even in the riot episode, the crew and actors had to minimize vibration in fear of setting off the mines below decks.

Reviewers didn't know how to describe the effect of the completed Battleship Potemkin, often referring to its stylized simulation of the attack on the Odessa Steps as a documentary. The film has no central characters, preferring to use cinematic technique to mold twenty or so individual 'actors' into a communal character, the 'awakened masses'. Everyone recognized the film as Soviet propaganda; what impressed them was its efficacy. Some Soviet epics about the revolution had hammered away with simplistic stories while hectoring the viewer with title cards assigning roles to its characters. Capitalists were always Evil, while the 'masses' were inspired by collective ideals. Potemkin sticks mostly with specifics. A cowardly priest conspires with the ship's officers against the men; he plays possum during the mutiny. We're revolted by the idea that the sailors would be forced to eat rancid meat overrun with maggots, and concerned when a group of protesting sailors are covered with canvas so as to make it easier for the firing squad to shoot them. Eisenstein would later have to defend the idea of historical embellishment when he was sued by a man who claimed to have been one of the sailors under the canvas. As it turned out, the canvas business was entirely made up for the movie, and the man's claim was thrown out of court.

The show has several main movements. The mutiny on the ship is followed by a slow passage as the citizens mourn the dead Vakulinchuk. A happy celebration on shore is interrupted (title card: "Suddenly ...") with the violent set piece on the Odessa Steps. This mostly self-contained sequence is probably the most celebrated of its kind in movie history. Building around one solid idea -- the craven Czarist troops are willing to massacre innocent civilians -- Eisenstein uses multiple montage techniques to tell several overlapping 'event stories' within the larger continuity of the sequence. A happy widow is terrorized by the marching, firing troops. Sympathizers crowd behind whatever cover they can find. A peasant mother's little boy is shot, and then trampled by the panicked crowd; she picks up the body and marches defiantly toward the advancing troops. A young mother collapses, knocking her baby's perambulator so that it bounces down the steps. A young student watches from the side. As the fleeing crowd reaches the bottom of the steps, mounted Cossacks appear with sabers to cut them down.

Eisenstein treats the sequence as a musical construction, with a rhythm of cuts that reinforces the marching gait of the troops. Many shots represent the viewpoints of the 'characters' in the scene -- the fallen boy, the student, a legless beggar who came to cheer the ship in the harbor. While the happy citizens applaud the Potemkin's raising of the Red flag (stencil-tinted red, as in original prints) the troops open fire. The moral outrage of the massacre is answered by the battleship's big guns, which fire upon the White Russian headquarters. By this time most filmgoers were surely ready to take up arms themselves.

Eisenstein wrote about Battleship Potemkin many times, and his revolutionary ideas of editing are now prime film school texts. A sailor reacts to an ironic message on a ship's plate by hurling it down, and Eisenstein repeats the action three times in a flurry of cuts. He repeats this cutting pattern with a scary saber-stroke to the camera at the end of the Steps sequence. But more impressive are Eisenstein's powerful compositions and control of movement within the frame. Mourners crowd a curving seawall, creating a rainbow-like arc of compassion stretching across the Odessa harbor. On the ship, the camera favors rigid symmetrical shots toward the ship's bow. Powerful trucking shots follow the running mass of citizens as they flee down the steps. The shadows of the troops and their rifles stretch forward, covering the mother carrying her son.

The ship's gun's first two shots at the White Russian palace bracket three fast images of lion-statues in front of a museum. The first is asleep, the second wakening and the third alert. The graphic message is immediately understood by any viewer: the sleeping proletariat has awakened, and is angry!

Kino's DVD of Battleship Potemkin comes with extras that rival Criterion for quality. The film is a new German restoration, and in a 24-minute documentary extra, Enno Palatas explains the film's strange history. In 1926 the original negative for Potemkin was exported to Berlin, where it was presumed that superior German labs could make better prints, even for Soviet use. This is where Edmund Meisel's excellent score was composed; this disc carries a new (2005) recording made in Germany. The film was repeatedly censored over the years, first by the Germans for violent content, and then by Stalin-era censors uncomfortable with depictions of citizens rising against authority ... left wing essentially became right wing. For the film's tenth anniversary Eisenstein had to limit his essays to what the authorities would allow to be printed, as his standing with the Communist Party was not secure. Not only were no uncut prints to be found, Stalin's revisionists had replaced a Leon Trotsky quote that began the film with one from Lenin. Even more sobering, one of Eisenstein's closest associates at the official Moscow film studio had just been arrested and executed, on vague charges of disloyalty.

We're told that our film-school copies of Potemkin came from a 1956 'restoration' that lacked a number of key missing shots, and I indeed remember being struck by odd continuity problems when I saw the film in the early 1970s. 1 Someone had even moved the execution-style killing of Vakulinchuk to the middle of the mutiny, making it just another violent event instead of a nasty act by a vindictive officer.

The disc set contains two full feature encodings. The first translates the inter-titles into English and the second leaves them in the original Russian with removable English subs. The shots are less cropped and more balanced than I've ever seen them. Overall contrast is good, although plenty of wear and fine scratches remain. Bruce Bennet provides a lengthy essay on the film and its restoration for an insert booklet. The clever packaging (designed by Bret Wood) uses original Soviet poster art. When unfolded, the disc holder reveals a wide original poster concept for the film. 2

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Battleship Potemkin rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Docu, Tracing Battleship Potemkin, photo gallery

Packaging: two discs in card and plastic disc holder in card sleeve

Reviewed: November 2, 2007

Footnotes:

1. The old Vagabond near MacArthur Park was a tiny revival film house whose interior was decorated with hi-con blow-ups of famous frames from Potemkin. I can't see the film without thinking of the pictures I saw for the first time in that theater!

Return

Not only is the "sailors under the sheet" made up, but also the whole Odessa steps massacre.

(photo: The Odessa Steps today)

Looking at a picture of the cover, it is the same poster I have by Anton Lavinsky. The cover of the booklet has the poster by the leading Russian artist of the time Alexander Rodchenko. The Stenberg Brothers (the greatest Russian poster artists) also did a couple of posters for the film. Which hopefully are included.

Alexandrov went on to make some of those Russian musicals that are in Eastside Story, notably Volga, Volga.

The fog sequence began as an accident. When heavy fog overtook Odessa, the crew decided that they would sleep in, as nothing had ever been shot under such conditions. Tisse insisted that the shots would be spectacular, even against Eisenstein's objections. The results were one of Eisenstein's favorite scenes in the movie.

The 1950 version is what you saw in film school. It was the hatchet job by Alexandrov and is absolutely terrible!!!!! The entire pacing of the film was ruined by the editing, yet film professors taught that it was Eisenstein's genius. The version that was restored by Sergei Yukevitch and Naum Kleiman (who I met in Moscow and who invited me to speak at the Sergei Eisenstein Masterclass at the Moscow film festival) in 1976 was the decent version that followed Eisenstein's basic plan. It is longer than the new version, because of the stretch printing used to bring the film to silent speed projection.

There have been complaints that the new version is from a Pal original and is badly interlaced. Was this noticeable?

If this has not already gone to press, you might mention Eisenstein's influence on directors like Hitchcock. The overlapped montage of the "Give us our bread" sequence deeply affected Hitchcock ( he wrote about it in the Encyclopedia Britanica article he authored) , and he used it most famously in the shower sequence of Psycho. I would not have used the word cartoonish for the lion scene, it was revolutionary for its time. Again, look at The Birds, where Tippi Hedren sees the man light the cigarette near the gasoline. Hitch uses three frozen shots of Hedren that animate as she turns her head in shock. Woody Allen and Brian De Palma also borrowed from the steps scene in their films. Allen reverses the lion sequence in Love and Death to show impotence. De Palma of course borrows for The Untouchables. Alain Resnais uses overlapping montage in Marienbad. The list is pretty long, if I put my mind to it.

Take a look at the earlier Ballet Mechanique by Leger, for some scenes that may have influenced S.M. Especially, the marching boots. Allan

Return

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |