| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Killer of Sheep: |

|

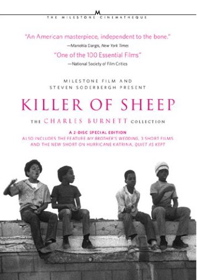

Killer of Sheep: The Charles Burnett Collection Milestone / New Yorker 1977 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 83 min. / Street Date November 20, 2007 / 39.95 Starring Henry G. Sanders, Kaycee Moore, Charles Bracy, Angela Burnett, Eugene Cherry, Jack Drummond Cinematography Charles Burnett Film Editor Charles Burnett Written by Charles Burnett Produced by Charles Burnett Directed by Charles Burnett |

The U.S. Library of Congress started its National Film Registry in 1989. Among the first fifty films chosen was a 1977 independent production that had yet to be given an official release. Killer of Sheep has always 'made lists' but saw relatively few showings. Its writer and director Charles Burnett appears in countless scholarly footnotes, yet few critics knew that he made other films as well. Killer of Sheep: The Charles Burnett Collection is a labor of love from Milestone, an independent distributor that supports its releases; for the past year or so they've been re-premiering Burnett's films on museum and repertory screens across the country.

Killer of Sheep plays out in Los Angeles' Watts ghetto and is loosely centered on Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders), a family man with a job slaughtering livestock in a meat packing company. Stan loves his wife and children but is becoming emotionally numb; when he isn't sitting silent at the dinner table, he lectures his nervous young son about becoming a man. Stan's wife (Kaycee Moore) can't get him to open up about his problems, which are all too obvious. They're stuck in poverty, the neighborhood is depressing and options are non-existent. Stan's friends are mostly unemployed; during the week they drink in the alleys and frighten the small children. Stan's only other visitors are a pair of criminals looking for a third partner. Stan is unresponsive to their challenge to join them in a robbery. His wife ends up chasing them away.

The film has no formal narrative. Burnett's camera observes life in Watts in fine detail, making dramatic speeches unnecessary. Watts is not a healthy place to grow up. Stan's small daughter makes her mother smile when singing along with the radio, but any kid over the age of five must deal with a hostile world. As if acknowledging how little their lives are worth, groups of little boys throw rocks at passing trains and play dangerous games in junk-strewn vacant lots. Smaller kids watch as their older brothers show how tough they are; Stan's son has fallen into the habit of crying for attention whenever he thinks things are unfair. At one point Stan sees some boys leaping across a rooftop gap between two second-story apartments, pretty much asking for a fatal accident. Stan doesn't intervene.

A measured pace lets us contemplate Stan's situation and his sense of self-worth. He's too mature to openly despair over things that are nobody's fault. At one point he buys a car engine from a man in an apartment, in an attempt to get his buddy's car running. They pay the money and haul the engine block down several flights of stairs, only to ruin it through a careless mistake. The incident is a perfect expression of pathetic hopelessness. Of course he'll waste his money. Of course the effort will end in useless humiliation.

Stan's wife cannot inspire him to relax or get out of the house, but she understands him too well to lose her temper. When she's alone in the house, she feels like a prisoner as well. In one scene they dance slowly to music from the radio, just taking quiet pleasure in being together. The moment is sublime.

In the 1970s almost all films with African-Americans in major roles were in the blaxploitation genre. Killer of Sheep distinguishes itself by ignoring commercial trends; it's also not an idealized family film like the popular Sounder. The comparison to the Italian neorealist films of De Sica and Zavattini only goes so far as Burnett does not impose irony or sentiment on the fitful, day-by-day lives of his characters. The acting is good where it counts, with Henry Gayle Sanders particularly good; the experience of two tours of duty in Vietnam shows in his eyes. Burnett filmed with friends and acquaintances and his players make up in authenticity what they sometimes lack in naturalness. The camera catches some great moments with the children as they mirror the self-destructive behavior of their parents. Some boys throw dirt at the freshly wash hung on a clothesline, laughing at the young girl whose day they've just ruined. Her reaction is a proud stare of contempt, refusing to give them the pleasure of seeing her upset.

Charles Burnett is one of the most acclaimed filmmakers to come from UCLA in the 1970s. UCLA had its share of pretenders and hustlers and fiery politicos, but Burnett is an accomplished cinematographer with serious artistic ambitions. Killer of Sheep is an intimate social document.

Milestone's Killer of Sheep: The Charles Burnett Collection contains the main B&W feature in an excellent transfer made from a full film restoration by the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Charles Burnett appears on a director commentary accompanied by Richard Peña of The Lincoln Center. The glitch that blocked an earlier theatrical release was the film's eclectic needle-drop soundtrack, with its songs by Paul Robeson, George Gershwin, Dinah Washington, Earth Wind & Fire and Faye Adams, to name just a few. Although the film restoration was extensive, the proper licensing of the music was Killer of Sheep's biggest hurdle.

The two-disc set contains an entire second feature and four of Burnett's short films, all restored and remastered. My Brother's Wedding is livelier, less experimental and more accessible than Killer of Sheep. Burnett's tone this time around shifts between comedy and darker concerns. Working in his parents' tailor shop, young Pierce (Everett Silas) comes into contact with everyone in the neighborhood. Pierce argues with his brother's upscale fiancée and is pressured into serving as his brother's best man. He has difficulty living up to other people's expectations. Some of his friends are in prison or already dead; he's constantly lectured by relatives, even when he helps the older folks by reading to them from the Bible. Pierce kids a pregnant customer and receives a chastizing for being 29 and unmarried. My Brother's Wedding is presented in two versions. A 118-minute cut from 1983 was screened only a few times before being shelved. The second encoding is much shorter.

The four shorts total about an hour's running time and are similar dramas about domestic situations. Several Friends is a promising early effort that includes a fight, a washing machine that needs installing and somebody's white girlfriend (future director Donna Deitch). The Horse (1973) is a moody color piece with a mostly white cast and a short-story ambience. When It Rains is from 1995; I believe we at one point glimpse the Watts Towers, behind restoration scaffolding. The new Quiet as Kept (2007) has a New Orleans/Katrina theme.

In another extra, the actors reunite for the first time in decades at Santa Monica's Dolores caf&e;. A new trailer is also included.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Killer of Sheep: The Charles Burnett Collection rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Commentary, Trailer, cast reunion; additional feature My Brother's Wedding (two versions and four short subjects.

Packaging: folding card case in card sleeve

Reviewed: November 8, 2007

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |