| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

El Cid |

|

El Cid Weinstein 1961 / Color / 2:35 anamorphic widescreen / 188 min. / Street Date January 29, 2008 / 2-Disc Deluxe Edition = 24:95; Limited Collector's Edition = 39.95 Starring Charlton Heston, Sophia Loren, Raf Vallone, Geneviève Page, John Fraser, Gary Raymond, Hurd Hatfield, Massimo Serato, Frank Thring, Michael Hordern, Andrew Cruickshank, Douglas Wilmer Cinematography Robert Krasker Production Design Veniero Colasanti, John Moore Film Editor Robert Lawrence Original Music Miklos Rozsa Written by Fredric M. Frank, Philip Yordan, Ben Barzman Produced by Samuel Bronston Directed by Anthony Mann |

El Cid has been waiting a long time for release, along with three other Samuel Bronston 'super-epics' of the 1960s. When Bronston's film empire came crashing down barely six years after it started, the films themselves were scattered to various owners, most of whom simply circulated 16mm pan-scan prints for television use. Although nothing can substitute for seeing a monster Road Show epic in its original 70mm format, the DVD image is clear enough to appreciate Bronston's works in their wide screen glory. The Weinstein Company has finally begun to restore and release these pictures for home video, under a branded line called The Miriam Collection. El Cid is the first to arrive, and will be followed by The Fall of the Roman Empire on April 20. It's presumed that 55 Days at Peking will appear later in the year. Weinstein's Limited Collector's Edition packages El Cid with plenty of extras including a commentary and featurettes with eye-opening insights into the Bronston filmmaking Empire.

El Cid is Bronston's most successful attraction and the one that made Hollywood believe that the 70mm Road Show epic was the class-act movie format of the future. The outwardly modest but impressively overachieving Bronston outpaced Hollywood by conceiving of filmmaking in global terms, with investors and partners on a political as well as financial level. Other producers might find their niche under the protection of a studio head, or by pursuing a splinter of the market untouched by the majors. Bronston instead re-imagined the entire game plan. Other companies and his own King of Kings units had found that locations and resources could be rented cheaply in Spain. Leveraging huge sums of money from private investors (notably one of the DuPonts), Bronston negotiated directly with the Spanish government. In exchange for enormous facilities and manpower at bargain rates, Bronston worked out an international finance deal with the Spaniards, helping the country earn foreign currencies. In addition to this legal money laundering, Bronston's deals also involved Spain's oil imports. Finally, and most controversially, Bronston's films provided a huge PR mechanism for Spain, a showcase of movie glamour that stimulated tourism and softened the image of fascist dictator Generalissimo Franco's repressive regime. 1

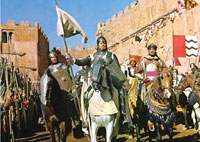

Grandiosity (in the non-pejorative sense) was the key to Bronston's success. Audiences seemed to have an unlimited interest in screens filled with thousands of extras, and his pictures were bigger than anybody else's. El Cid isn't as 'big' as the films that followed it, but the quality of its physical production far outdistances spectacles filmed in Culver City or North Hollywood. Even the costumes for the extras are authentic, and everything made of fine leather, carved wood or Toledo steel is the genuine article. In Europe Bronston found old world designers and craftspeople that made MGM's plaster and canvas approach look like the work of amateurs.

Bronston hired the best of the best of talent that had worked on previous Italian epics like Ben-Hur, men like stunt arranger Yakima Canutt and editor Robert Lawrence. Editorial maven Verna Fields handled the film's exemplary 6-track audio editing. On King of Kings Bronston used the 'sensitive' director Nicholas Ray for the character scenes and farmed out the action to second unit experts. For El Cid he secured the services of Anthony Mann, a director of highly physical westerns, and whose career had faltered with the failure of Cimarron (an epic remake crippled by studio interference) and the ignominy of being fired from Kirk Douglas' Spartacus. Ambitious and motivated, Mann would take firm control of El Cid and infuse it with his own dynamic visual sensibility.

Add highly paid superstars Charlton Heston and Sophia Loren, and El Cid is a knockout. Modern attempts at epic grandeur pale against the real thing: El Cid has blood, passion and a grand theme.

El Cid thinks BIG all the way through, and maintains its strong storyline by constantly reinforcing its simple but serious theme. Rodrigo de Vivar chooses 'destiny' over domesticity, giving us three hours of pageantry and flying broadswords, interspersed with some nicely-framed scenes of Charlton Heston cuddling up to Sophia Loren. Ace blacklisted writer Ben Barzman (of the pro-communist drama Give Us This Day (Christ in Concrete)) apparently re-wrote the script at the last minute, securing Loren's commitment and giving El Cid its clean thematic lines. He also sneaks in an interesting incestuous relationship between Prince Alfonso and his sister Urraca. Geneviève Page plays the duplicitous princess as a troubled, sly schemer.

Epics are known for klunker dialogue, which is conspicuously absent from El Cid. Only a few moments inspire unintended smiles, in particular a big laugh of agreement when a mother superior tells the va-voom Loren that she belongs in the outside world instead of a convent. Ms. Loren's eye makeup is perhaps the only anachronism in the whole film. Everything else is museum-grade authentic, with the input of respected historical expert Dr. Ramon Menendez Pidal silencing potential claims of inaccuracy. Real castles and walled cities are in every scene, in some cases with add-on fake architecture to hide details wrong for the period. Even more impressive are the many wide angles that show clean landscapes all the way to the horizon, with nary a radio station or high power transmission line in sight. Away from the big cities, Franco's Spain was still back in the 19th century.

The energetic sword fights were overseen by expert Enzo Musumci Greco (of Harryhausen skeleton fame). The mayhem looks entirely convincing, with big chunks of leather flying off the saddle that Heston must use as an improvised shield. Rodrigo's first joust-battle is easily the best of its kind, narrowly upstaging the set-to between Robert Taylor and George Sanders in Ivanhoe: in a startling but typical bit of Anthony Mann violence, Christopher Rhodes's horse runs Heston over as if it were a Mack truck. 2

Heston and Loren provide the film's jolt of star power. The Italian beauty earns most of her million-dollar fee just by being there, while Heston carries the show on his broad shoulders. Heston is the physical equal of any bigger-than-life character, and in 1961 was at the top of his game, exuding the raw authority that brings idealistic and noble characters to life. Rodrigo has the commitment and force of will to play a man motivated by his King and his God; we believe that an entire nation would rise up and beg him to lead them.

But the key to El Cid's success is Anthony Mann. In his westerns Mann had developed the visual skill to create drama through dynamic compositions, arranging characters in ways that expressed their relationship to one another. Man of the West has a nearly perfect three-way stalking scene in a ghost town that forces us to share Gary Cooper's entrapment. Cimarron turns the merely big land rush scene from the original into a tour-de-force. In El Cid Mann contrasts compositions from formal paintings with huge close-ups, and paces the action so that we appreciate every visual set before us. Many films have impressive production design; in El Cid we inhabit it along with the characters.

Mann's westerns by and large were not myth-making efforts in the John Ford mold. The failure of Cimarron probably stems from the fact that its hero becomes a wandering, largely absent bum, making the choral song on the soundtrack seem facetious. But most of Mann's western heroes are embroiled in solemn vendettas, which segues perfectly into the world of El Cid where chivalry is threatened by treacherous ambition. All of Mann's tortured gunslingers find personal redemption except for Gary Cooper's Link Jones, who looks beyond the bleak horizon and sees nothingness. El Cid does the same and sees his Destiny: God, Spain and King Alfonso. 3

El Cid gives Spain's hero the deluxe treatment, as the modest Rodrigo transforms himself into a living legend. Mann conjures a classic ending that compares Rodrigo with Christ, defying death itself. The sun strikes Rodrigo's armor, Miklos Rozsa's score hits a chilling organ note, and the leader who expelled the Moors from Spain rides off to his destiny. 4

As Rodrigo's father, Michael Hordern gets one really powerful moment, defending his good name in court. Raf Vallone is a soulful traitor and Douglas Wilmer is a 'good' Arab, the kind who allies with Christians against his own people. Hurd Hatfield and Massimo Serato make lesser impressions while Herbert Lom commands the screen with just his eyes. A decade later, director John Milius would swipe a number of castles and motifs from this picture for his The Wind and the Lion, including the iconic image of Lom's Moorish chieftain, with his face wrapped in black cloth, staring down the camera like a Riffian Bela Lugosi. That image is the main graphic on the Milius film's poster!

Weinstein's Limited Collector's Edition of El Cid looks stunning in a new enhanced transfer. Savant saw the film in its 1993 70mm restoration, and while DVD can't match 70mm for detail, the colors overall have been smoothed out considerably. Criterion released a pricey laserdisc in the middle 1990s. Even it showed considerable dirt and damage, but this new release seems to have corrected most of it. In only a few shots are the colors flat, and a couple of slightly out-of-focus angles may have always been that way. 5

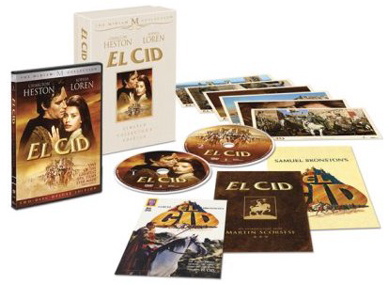

The Weinstein Brothers have dedicated El Cid to their mother by inaugurating "The Miriam Collection", a branded line given prominence in logos and on the disc cover. The disc extras are definitely worth bringing home to mother. The Limited Collector's Edition comes in a handsome beige box. In it one finds the Two Disc Deluxe Edition, which contains the following attractions:

The commentary is with Samuel Bronston's son William, and Neal Rosendorf, a historian and author of a Bronston biography. It's naturally very long and discusses much more than the movie at hand. After a while, we do tire of the pair's endless superlatives for the movie, which is an excellent epic but not the pinnacle of 20th century art. The discussion keeps coming back to Bronston's dealings with Franco and DuPont, hinting at darker doings without connecting the dots. 6

Radio promo interviews from 1961 present Charlton Heston, Sophia Loren and Heston's wife Lydia answering questions about the historical background of the characters and their approach to their roles. Disc one finishes with text filmographies and a still gallery.

Disc two has the long-form featurettes, all of which are new. Hollywood Conquers Spain: The Making of An Epic (23:56) uses behind-the-scenes stills and film (much of it from other Bronston epics) to chart the massive production, described by C. O. Doc Erickson as 'leaking money in all directions.' The testimony pretty much indicts writer-dealmaker Philip Yordan and Associate Producer Michal Waszynski as using the Bronston shows to line their own pockets. Samuel Bronston: The Epic Journey of a Dreamer (52:20) retraces the producer's entire life, with input from his biographers Neal Rosendorf and Mel Martin, as well as Bronston's son, other relatives and Ben Barzman's widow Norma. The producer comes off as a sort of benign wheeler-dealer, dealing in huge amounts of money and never using his position to amass riches -- something that cannot be said about some of his closest confederates.

Behind The Camera: Anthony Mann and El Cid (17:22) is an okay look at a career that began in the cheapest studios in Hollywood and eventually led to two of the biggest productions ever assembled. Anthony Mann's previous work is only lightly sketched but viewers already familiar with the director will enjoy seeing excerpts from a rare TV interview made not long before his sudden death in 1967. Miklos Rozsa: Maestro of the Movies (30:11) presents an overview of one of the most respected film composers. It concludes with several inspirational and touching memories from John Mauceri about the elderly Rozsa. Preserving Our Legacy: Gerry Byrne on Film Preservation and Restoration (7:38) is less easy to pin down, as the charming Gerald Byrne isn't sufficiently identified. Besides describing his job of going through thousands of cans of film, we aren't even sure when he was doing this work -- for the 1993 restoration? Now? The DVD lists separate credits, which I believe are for these featurettes: Produced by Shannon McIntosh, Issa Mizrahi, David Rodriguez; Edited by Adam Bernardi.

The disc 2 features end with 1961 and 1993 trailers for El Cid. The only audio track is English Dolby 5.1 and the menus give a choice of subtitles in Spanish and English for the hearing-impaired.

The only paper extra for the 2-Disc Deluxe Edition is a heartfelt text intro by Martin Scorsese. The Limited Collector's Edition adds a handsomely published reproduction of the original souvenir program, a repro of the original Dell comic book (15 cents!) and a packet of six color stills printed on card stock.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

El Cid (Limited Collector's Edition) rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Many. See above

Packaging: Keep case in heavy bound box with booklets and still inserts.

Reviewed: January 13, 2008

Footnotes:

1. The commentators on El Cid assert that the PR glorification of Franco's Spain went even further, with El Cid standing in for Franco himself, defending his Catholic faith and reuniting his nation against hostile outsiders -- 'Evil' Moors = "Evil" Communists. Beyond lamenting the fact that Bronston's production benefited a fascist dictatorship (a few millions and all political crimes are forgotten) it's fairly pointless to carry this thread further. It's not the same as if Halliburton started making movies with Iran, or making the Bin Laden bio into a hit miniseries. Franco's ministers were reportedly delighted to support a super-epic deifying their national hero El Cid. Bronston can't be faulted for not suggesting alternates like "The Guernica Story", "The Siege of Barcelona" or the heartwarming "Meet Federico García Lorca."

The commentators allude to but do not pursue the odd mutual aid alliance between Bronston, Fascist Spain, Big Oil and The DuPont Corporation. Conspiracy theorists and Marxists would surely jump all over this one.

Return

2. Mann always made career capital from explicit/implied violence. In Raw Deal John Ireland tries to impale Dennis O'Keefe's eye on the sharp points of a mounted deer's antlers, and in Border Incident George Murphy is grotesquely dismembered by a giant farm cultivator. In his westerns, James Stewart suffers rope burns, is dragged through a fire and is held down while a bad guy shoots a .45 caliber hole in his hand (The Man from Laramie). Mann was reportedly fired from Spartacus but the choreography of the combat in the gladiator school may have been heavily influenced by his preparations. Unlike most movies, when somebody is wounded in a Mann film, the audience feels it.

Return

3. Actually, the closest Mann film to El Cid is probably Devil's Doorway. Native American Robert Taylor returns from fighting in the Civil War to see his rights and property stripped away by opportunists stealing Indian lands. He's forced to fight his own country, and loses. Mann's The Furies posits a perverse Ponderosa where a cattle baron turns an entire territory into his personal kingdom, oppressing Mexican Americans and even issuing his own currency. I'm surprised that these 'subversive' pictures didn't put Mann on the blacklist; perhaps his success and his association with James Stewart spared him that.

Return

4. El Cid's righteous expulsion of the Moors now comes off as an odd jest worthy of Monty Python's 'whatever did the Romans do for us?' gag in The Life of Brian. The Muslims (Mohammedans?) brought little things like architecture, science, mathematics, civic waterworks, healthy eating and basic hygiene to one of the most backward corners of Europe -- the joke was that the Moors smelled good while the Spanish nobles used perfume instead of bathing. In general terms, the Moorish administration of Spain tolerated Christians and Jews, while the Christians tended toward bloody ethnic cleansing.

Return

5. Reader John Wilson has the old Criterion laserdisc and tipped Savant off thusly: "The first place to look for evidence of further restoration of the Scorsese print is just before the intermission. A crane shot shows Loren and the nuns walking toward a wall at the convent to watch Heston and his army ride away. Across this shot is a really bad, ugly tear in the print." In the new transfer, this flaw has been repaired.

Return

6. Correspondent Ed Sullivan has found a well-researched paper by Samuel Bronston biographer Neal Rosendorf that sheds new light on the producer's Spanish productions including El Cid. It's called Hollywood in Madrid: American Film Producers and the Franco Regime, 1950-1970 and can be found at this URL.

Return

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © 1999-2007 DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |