| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

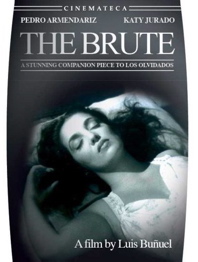

The Brute |

|

The Brute Facets / Cinemateca 1953 / B&W / 1:37 flat full frame / 83 min. / El Bruto / Street Date October 23, 2007 / 24.95 Starring Pedro Armendáriz, Katy Jurado, Rosa Arenas, Andrés Soler, Roberto Meyer Cinematography Augustin Jiménez Art Direction Guenther Gerszo, Roberto Silva Film Editor Jorge Bustos Original Music Raúl Lavista Written by Luis Buñuel, Luis Alcoriza Produced by Gabriel Castro, Óscar Dancigers, Sergio Kogan Directed by Luis Buñuel |

Luis Buñuel's El Bruto is such an effective drama, we're surprised to learn that its famous director considered it a compromise. One of the bigger successes of his Mexican period, this unblinking criticism of class differences has two great performances by Pedro Armendáriz and Katy Jurado. She won a best supporting actress Ariel award in Mexico for her portrayal of a fiery seductress -- the real thing, not the Hollywood 'Mexican spitfire' cliché.

The script by Buñuel and his frequent collaborator Luis Alcoriza pits rebellious tenants against a pitiless landlord,. It is more concerned with social dynamics than political advocacy: when pressured by uncertainty and fear, the working-class poor are just as brutal as the selfish businessman.

El Bruto's immediate attraction is its star chemistry. Pedro Armendáriz and Katy Jurado heat up the screen. Jurado's Paloma is obviously frustrated; she amuses herself by feeding her father-in-law wine by dipping her finger and letting him suck it. Paloma perks up immediately upon seeing Pedro's muscular arms. When he uses his elbow as a nutcracker, she knows he's her kind of man. Pedro cleaved whole cows in two at the slaughterhouse, a skill that needs to be refined if he's to carve steaks and ribs for the customers. The script finds numerous ways to smuggle scenes of sexual excitement past the Mexican censors.

In the postwar period, scripts that perceived flaws in the American way of doing things were often tagged as suspicious. But our so-called subversive writers never came up with anything as blatant as El Bruto. A cruel landlord arrives with cops to announce imminent evictions and is almost stoned by his outraged tenants. When the landlord's lawyer says that their grievances belong in the courts, the tenants angrily respond that the law and justice are only for the rich. The landlord hires a thug, who kills one 'agitator' and threatens to dash a woman's baby against a wall. Up to a certain point, El Bruto clearly represents the struggle between management and labor, or the haves and have-nots.

But Buñuel's character complications point the story in more interesting directions. As in all of his Mexican movies (especially Los Olvidados), Buñuel refuses to idealize the poor or even to accept them as a class capable of political unity. Pedro lives with an impoverished girlfriend and her family of greedy freeloaders. The mother sits in bed smoking as she claims to have no money, and when Andrés gives her some, her brother and sons steal it. The apartment dwellers swear to stick together to defeat Andrés, but fall apart as soon as they are threatened. The men waste their time trying to catch Pedro, when their real enemy is their landlord. They cruelly ostracize Meche, just for being seen in Pedro's company. "The system" is bad, but Buñuel sees no solution to its injustices, which are based in human nature.

Yet the ultimate malice is still attributed to the ruling class. Andrés Cabrera wields unjust power over his household and the city around him. He's eventually revealed to be dishonest in his relationship with Pedro, who is more than just a kid he befriended in the streets. When Pedro finally learns the score, Andrés has a lot to answer for.

According to Raymond Durgnat, Buñuel was forced to rewrite El Bruto to add the uplifting romance between Meche and Pedro. This perhaps explains Pedro's fluctuating IQ; in early scenes he's a dumbbell's dumbbell, but with Meche he becomes much more articulate and sensitive. The Meche-Pedro connection is a tired cliché (sweet innocent redeems violent lout) but it would still seem essential to the working-out of the story. Meche's presence motivates Paloma's rage and cues the ferocity of the final scenes, when Pedro discovers that his boss's kindness masks a different kind of contempt. After a supremely violent killing, Pedro ends up facing Buñuel's idea of a real enemy, the faceless cops.

It's easy to rush to judgment when interpreting Buñuel's odd touches. The landlord's feeble father steals candy, wears an Iberian beret and speaks with a Castilian accent. Is he meant to represent the corrupt Franco Spain, or did Buñuel just like the particular actor, who may have been a fellow exile from Fascism? At one point in the film Pedro hides from the murderous tenants in Meche's yard, and kills a hen to keep it quiet. Grateful for her protection, he then replaces the hen, beginning their relationship. At the end, the horrified Paloma comes face to face with a rooster, that stares (accusingly?) back at her. It's the final note in the story, and difficult to read. What is this chicken business all about? Have deleted scenes obscured its meaning, or does the rooster simply represent, 'Chickens come home to roost'?

Facets and Cinemateca's DVD of The Brute (El Bruto) is an acceptable transfer of this fine Buñuel picture and a great opportunity to enjoy yet another Katy Jurado performance -- she's been remarkable in every film I've seen her in. The print isn't perfect but the transfer appears to be from quality elements. Raúl Lavista's score also comes across well. No extras are included. Savant reviewed Buñuel's A Woman Without Love a couple of months back, and is eagerly awaiting hiss Susana, a much more overtly surreal and subversive fantasy-soap opera.

I don't know of any critic or reference book that refers to El Bruto as The Brute, but that's how Cinemateca and Facets have chosen to list this Mexican classic.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

The Brute (El Bruto) rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Good

Sound: Good

Supplements: None

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: January 12, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © 1999-2007 DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |