| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

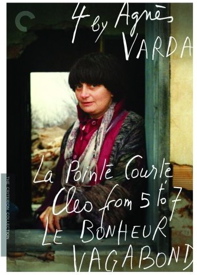

4 by Agnés Varda |

|

4 by Agnés Varda Criterion Street Date January 22, 2008 / 99.95 Written and Directed by Agnés Varda |

Criterion's four-disc set includes a full roster of extras, with Ms. Varda talking about her work in interviews both vintage and new. The collection gathers a few of her rarely-screen short films as well.

La Pointe Courte

Criterion 419

1954 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 80 min.

Starring Silvia Monfort, Philippe Noiret

Cinematography Paul Soulignac, Louis Stein

Film Editor Alain Resnais

Agnés Varda's claim that she was untouched by prior film-going experiences may be true, if we consider that she started as a photojournalist. But her first film La Pointe Courte suggests an eclectic range of sources. Varda switches back and forth between two separate narratives, using an 'alternating chapter' format that she says was inspired by William Faulkner. An almost ethnographic story follows the fishermen of a small French village as they resist a government ban on fish from specific waters; the locals ignore the official claims that the waters are polluted. The villagers are observed as a communal whole, whether gossiping about local tragedies, watching one of their own go to jail or celebrating with amusing games of jousting with boats (this has to be seen to be believed).

Running parallel with this narrative is the story of a married Parisian couple. Lui (a rather slim Philippe Noiret in his 5th film) has invited his wife Elle (Silvia Monfort) back to his hometown. They wander the waterfront and beaches engaging in desultory discussions about their relationship, using the kind of art film-speak associated with Antonioni and Bergman films still a decade away. The two stories take place in the same location, but barely intersect.

Agnés Varda's visuals do not look like the work of a first-time director on a tiny budget. Many shots make use of smooth, unobtrusive dolly moves. Varda's camera stays at a slight remove from a slight remove from the townspeople, staying calm even when observing the death of a sickly child. Most viewers prefer this section. By comparison, the episodes with the unhappy married couple are purposely stilted. Varda reports that her actors were not thrilled by her instructions to say all of their lines in an unemotional deadpan, a directing strategy associated with the later films of Robert Bresson. Even more weirdly, Varda at one point places her actors in mannered close-ups that look almost exactly like setups in Ingmar Bergman's Persona. La Pointe Courte shows Ms. Varda as an experimental filmmaker exploring creative choices in her very first film.

La Pointe Courte makes its debut on home video in a handsome B&W transfer. Agnés Varda discusses the film in a new video interview and is also seen in a 1964 French television show. Alain Resnais was her editor; the director was so impressed by her raw dailies that he decided to assemble the film in the simplest way possible.

Cléo from 5 to 7

Criterion 73

1961 / B&W / Color / 1:66 anamorphic widescreen / Cléo de 5 à 7 / 89 min.

Starring Corinne Marchand, Antoine Bourseiller, Dominique Davray, Dorothée Blank, Michel Legrand, José Luis de Villalonga

Cinematography Paul Bonis, Alain Levent, Jean Rabier

Production Design Jean-François Adam, Bernard Evein, Edith Tertza

Art Direction Bernard Evein

Film Editor Pascale Laverrière, Jeanne Verneau

Original Music Michel Legrand

Produced by Georges de Beauregard, Carlo Ponti

Varda's celebrated second feature Cléo from 5 to 7 is one of the masterpieces of the French New Wave, a film with an interior life that couldn't be created on a commercial production line. The story takes place more or less in real time, following pop singer Cléo (Corrine Marchand) around Paris as she marks time waiting for a final diagnosis from her doctor, who has told her that he suspects cancer. Rattled by the pessimistic verdict of a Tarot card reader (a title sequence in color), Cléo goes shopping for a hat with her personal assistant Angèle (Dominique Davray), takes a visit from her neglectful older lover (José Luis de Villalonga) and spends a few minutes trying out new tunes with a spirited pair of songwriters (including the film's composer, Michel Legrand). She then accompanies a friend, nude model Dorothée (Dorothée Blank) on an errand to deliver a film to a theater across town. Depressed, Cléo ends up in a park, where she connects with Antoine (Antoine Bourseiller), a soldier on leave. As 6:30 approaches, they head to the hospital, to hear the verdict on her diagnosis.

Cléo from 5 to 7 is first of all a near-magical time machine trip back to Paris, 1961. Cléo spends at least half the film wandering in public places, where every detail of clothing, cars and street corners is now of special interest. Varda's experiment in real time actually lasts until about 6:30. Various clocks along the way stay fairly close to the correct time, as also happens in Fred Zinnemann's High Noon. This detail doesn't come easy, as many of the clocks we see are public displays not likely to be changed for a low budget film.

Varda's film is a potent character study. 'Cléo Victoire' is a vain and self-centered celebrity, and quite perturbed that her serious cancer problem doesn't go away after one of her pouts. Tall and beautiful, she's the envy of most women. She tries on hat after hat and finally has to admit, with a sigh, that 'Everything suits me.' Cléo complains that her rich lover hasn't time for her, and then unloads her moodiness on her two songwriter friends, who roll in like a pair of traveling comedians. They have several good songs for her, the best of which is a sad ballad that flings Cléo back into a rotten mood.

Ditching her fancy wig, Cléo heads once again into the city streets, this time with a more open mind to the world around her. Instead of complaining that her friends aren't entertaining her, or loitering about trying to be recognized, Cléo settles into a more reflective mood. Living with nagging doubt is a humbling experience. Too proud to break down, she eventually alters her view of the world around her. Cléo has only a few minutes to spend with an interesting new friend, a soldier who amuses her. He's going back to combat duty in Algeria, an uncertain future that Cléo now understands. The main pleasure of Cléo from 5 to 7 is watching a shallow, vain woman find some perspective on her predicament, to the point of identifying with someone else's problems.

Agnés Varda's accomplishes a rare thing with Cléo from 5 to 7. Her real-time experiment is not a gimmick but a way of perceiving a character's emotional transformation in depth. Varda makes her plan obvious by starting scenes with superimposed titles, like "Cléo from 5:05 to 5:08." The B&W film begins with color shots of Tarot cards, further reminding the audience of the artifice at play. Strangely, Varda's careful photography and fluid tracking shots are much less intrusive than the current vogue for movies contrived to emulate video records taken from camcorders. Varda's camera thinks nothing of panning from Cléo to offer a 'subjective' viewpoint of what she sees, and then panning back to her as an objective observer. Experiencing the 'reality' of a person's problems in real time isn't as easy as nailing them with a magical floating camera. Film conventions make Varda's camera unobtrusive, even in masterful takes that track Dorothée's car as it winds through the Parisian boulevards.

Varda found Corrine Marchand in Jacques Demy's Lola, from the same producer. Perceiving the need to interrupt the somber mood, Varda inserts a brief short subject seen when Cléo visits a projection booth. It's a parody of silent films starring Jean-Luc Godard, Anna Karina, Jean-Claude Brialy, Eddie Constantine and Sami Frey, all in bit parts.

Cléo from 5 to 7 is an improvement on Criterion's first release from 2000. The enhanced image is very sharp and detailed, allowing us to see much more in the many wide street scenes. The new Varda interview has been expanded into a longer docu that reunites the director with Corrine Marchand and Antoine Bourselier. More actors appear in a short revisit to the film's Paris locations, and a shorter piece examines paintings by Hans Baldung Grien that inspired the film. A clip from a 1993 French talk show presents Madonna explaining that she wanted to do a remake of the picture, a project that died when the studio expected a formal script. The original trailer presents the film as a mystery.

Two Varda short films are included. The little silent parody Les fiancés du pont Macdonald is presented in a stand-alone format, with Varda explaining why she put it in the movie. She's proud of the fact that she got Jean-Luc Godard to remove his dark glasses, to reveal his handsome face. L'Opera Mouffe is an odd short from 1958 that juxtaposes shots of the pregnant Varda with scenes taken in the courtyard and food stalls of an out-of-the-way Paris street. Georges Delerue did the music; Dorothée Blank and Antoine Bourselier appear as naked lovers.

Le Bonheur

Criterion 420

1964 / Color / 1:66 anamorphic widescreen / 80 min.

Starring Jean-Claude Drouot, Claire Drouot, Marie-France Boyer

Cinematography Claude Beausoleil, Jean Rabier

Production Design Herbert Monloup

Film Editor Janine Verneau

Original Music Jean-Michel Defaye

Produced by Mag Bodard

The most calculated film in the collection is Le Bonheur, a straight-faced story of a happy marriage interrupted by infidelity, told in a way that begs interpretation. The movie is stylized in color just as thoroughly as The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, the romantic musical by Varda's husband, Jacques Demy. Varda even transitions between scenes by fading to solid colors instead of black. The two pictures, however, couldn't be farther apart in theme. Le Bonheur (Happiness) dissects the very notion of love and harmony in a way that makes romance seem a cruel fraud.

Happily married François and Thérèse are played by Jean-Claude and Claire Drouot, a real married couple; their two young children also play roles. François works as a carpenter but spends happy evenings and weekends with his family. The film starts on an idyllic picnic in a sunflower field. When the children obediently take naps, the married couple can make love. François and Thérèse are calm and thoughtful and get along well with their parents; no conflict even seems possible. The problems of the outside world never intrude. The setup is so idealized, it's almost sinister, as if 'the perfect' marriage came with some product bought in a store, or perhaps out of a seed pod from outer space. We dread finding out what disaster will ensue.

The problem ends up being a very simple one. François falls for Émile Savignard (Marie-France Boyer), a friendly blonde at the post office. He drifts into her bed without so much of a pang of conscience, and they build a separate relationship. Émile is content to be the second woman in François' life; he talks about their situation in generic platitudes. On another Sunday picnic François decides to be honest with Thérèse and explains his infidelity in tones of bland innocence. He reasons that he's bringing 'more love' into their lives; keeping Émile on the side is no different than tasting fruit from a new apple tree. Thérèse is troubled only for a moment and then accepts her husband's words; she seems almost enthusiastic as they begin to make love (those perfect kids are taking naps again).

At this point Varda pulls the rug out from under everything -- the characters, the movie and many of our preconceptions about the concept of happiness.

Le Bonheur is relentlessly beautiful and idealized; even the carpenter's shop looks like it never gets dirty. Everyone we meet is considerate and well-spoken. Thérèse sews a wedding dress for the girl next door, and we see a picture-perfect wedding. Varda's apparent intention is to undercut the very notion of happiness in relationships, and leaves it up to viewers to argue the details. Are we only 'happy' when we're ignorant? I'll drop the discussion here, as the film's real revelations occur after a plot point that should not be spoiled. Once again, Varda's film neither looks or plays like anyone else's; it's an original from the core out.

Seen in this enhanced transfer with beautifully restored color, Le Bonheur looks much better than 16mm prints that circulated in the 1980s. Criterion's extras are particularly good. Actresses Marie-France Boyer and Claire Drouot discuss their contrasting roles in a new interview. A round table of journalists and authors debate the content and meaning of the film -- honestly, this one's a guaranteed conversation starter. Varda contributes two brief short subjects asking passers-by what happiness means to them.

Actor Jean-Claude Drouot returns to talk with locals who worked on the movie 42 years later, a featurette that becomes humorous when two townspeople chide him for not returning borrowed clothing. Drouot's fans know him as a Robin Hood-like character from French television, and ask him to sing the theme song!

Du côté de la côte is Varda's highly amusing 1958 short subject about the French Riviera. It's a free-association travelogue packed with visual surprises. A 1964 TV show has behind-the-scenes footage from the Le Bonheur set, and Varda talks about the movie in a 1998 interview. A trailer is included as well.

Vagabond

Criterion 74

1985 / Color / 1:66 anamorphic widescreen / 105 min. / Sans toit ni loi

Starring Sandrine Bonnaire, Macha Méril, Yahiaoui Assouna

Cinematography Patrick Blossier

Film Editor Patricia Mazuy, Agnés Varda

Original Music Joanna Bruzdowicz

Produced by Oury Milshtein

Agnés Varda developed Vagabond while studying the phenomenon of homeless drifters in France. She interviewed many to make up her composite story. To her surprise, women were on the roads as well; one that contributed the most was given a bit part in the film.

The beautiful Sandrine Bonnaire (Suzanne in À nos amours) plays Mona Bergeron, who has neither 'roof nor law'. Mona gives out her correct name out only once or twice in the story, as she adheres to a strict rule of independence. Unfortunately, Varda's deterministic tale begins with the discovery of Mona's frozen body in a muddy field. We spend the balance of the movie finding out how she gets there.

Mona carries a tent with her and sleeps wherever she can pitch it, even in the snow. She bums about rural France, asking for handouts and volunteering to do bits of work when she can. She offers thanks to no one and is quick to assert herself when truck drivers drop suggestive hints. The colorful film picks up Mona as she emerges from the sea in a long shot, as if director Varda were imagining the girl beginning in a state of innocence. Mona spends most of the film covered with dirt, her hair a tangled snarl.

It's a rough time all around. Mona makes few connections, not even with Madame Landier (Macha Méril), a specialist in tree diseases who for a time keeps Mona as a traveling companion and brings her food in the car. Landier is attentive and concerned, but like most upscale acquaintances, she has difficulty getting past how dirty Mona is. Mona literally smells, an issue more important than any concern that she might be a thief or a drug addict. Even though they've shared many conversations, Mona leaves Mme Landier with hardly a wave goodbye.

Mona's encounters vary in tone, which makes Vagabond more bearable than Robert Bresson's later exercises in cold-blooded misanthropy, L'Argent for one. Mona barges in on an impossibly old lady (Marther Jarnias) and the two share a great laugh together. Unfortunately, Mona's encounters become less comforting as the story unfolds. She falls in with a group of troublemakers and hooks up for a few days with a boy who has ideas about pimping her out for money.

Mona's most discouraging encounter occurs when she stays for a while with a Moroccan farm worker (Yahiaoui Assouna), learning from him how to tend a vineyard. We can tell that Mona is pleased when he invites her to live with him, and tells her that his fellow workers will welcome her when they return. Unfortunately, the workers insist that Mona must leave. After that, her luck goes quickly downhill. She's raped in the woods, and a fire in a crash pad causes her to lose her essential sleeping bag. Wandering into a crazy festival day, she's soaked in a wine vat by some scary 'celebrants'. Nobody survives without protection from the elements.

Varda's film is clearly sympathetic to Mona but refuses to sentimentalize her. Mona may seem a mystery but she's really that timeless kind of character who refuses to live on anybody's terms but her own. Sandrine Bonnaire won a French best actress award for the role. Most of the rest of the cast are non-pros that Varda discovered on the road. The movie has a fine sense of the outdoors and of the changing face of France -- many of the humble workers are North Africans. Varda breaks the naturalistic feel of the movie with a number of beautifully-filmed transition scenes, tracking shots accompanied by Joanna Bruzdowicz' elegant music. Vagabond is a difficult film to forget.

Vagabond's soft colors are nicely transferred in Criterion's enhanced transfer. Agnés Varda participates in a very good featurette that revisits filming sites; Sandrine Bonnaire contributes an interview as well. Another featurette shows Varda visiting Marthe Jarnias, the charming old lady that has the funny scene with Bonnaire. We see clips from a decomposed Varda short subject in which the elderly Jarnias appeared, nude.

A 1986 radio interview presents Varda talking to writer Nathalie Sarraute, an inspiration for the film; composer Bruzdowicz' music is given a special appreciation in an extra that collects all of the film's 'special' interstitial transition scenes mentioned above. A trailer is included as well.

A fat booklet for 4 by Agnés Varda contains film introductions by Agnés Varda and essays by Ginette Vincendeau, Adrian Martin, Amy Taubin and Chris Darke. Criterion's disc producer is Alexandre Mabilon

All of the films bear the Ciné-Tamerlis logo, which implies that Varda has both ownership and control; she's been restoring and preserving both her own films and those of her late husband for years now. Tamerlis may be a cat's name; cats often get special treatment in Varda's films. In La Pointe Courte they're everywhere, often contributing substantially to the fabric of the story. At a perfect moment in the dialogue between La Pointe Courte's married couple, a sleeping cat in the middle of the frame suddenly decides to wake up and stretch. For some directors, magical things just seem to happen.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

4 by Agnés Varda rates:

Movies: all Excellent

Video: all Excellent

Sound: all Excellent

Supplements: see above

Packaging: Four plastic and card disc holders in card sleeve

Reviewed: January 24, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © 1999-2007 DVDTalk.com All rights reserved | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |