| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

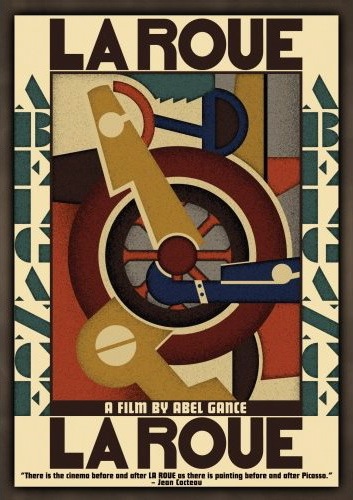

La roue |

|

La roue Flicker Alley / Blackhawk 1923 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 270 min. / Street Date May 6, 2008 / 39.95 Starring Séverin-Mars, Ivy Close, Gabriel de Gravone, Pierre Magnier Cinematography Léonce-Henri Burel Art Direction Robert Boudrioz Film Editors Marguerite Beaugé, Abel Gance Original Music Robert Israel (new score) Produced by Abel Gance, Charles Pathé Written and Directed by Abel Gance |

French film artist and pioneer Abel Gance is noted as the greatest European director of the 1920s, yet much of his work remains elusive in its original form. Napoleon (1927) was the subject of a major reissue in the early 1980s but a new and more complete version has since been finished by Kevin Brownlow. New restorations of Gance's 1919 J'accuse and his La roue (The Wheel) are set to premiere on the Turner Classic Movies cable channel late in April, 2008. Not long afterward, the Flicker Alley label will release a two-disc DVD set of La roue, a 1923 masterpiece credited with influencing filmmakers around the world, from Sergei Eisenstein to Akira Kurosawa.

La roue is an epic melodrama that extends the vocabulary and grammar of cinema through innovative editing and experimental filming techniques. It's a psychological study of human desire that blends epic realism with intense visual poetics. Made before producers took control of the purse strings of filmmaking, La roue shows Abel Gance running free with his camera, setting new challenges for his actors and technicians and reaching for new means of cinematic expression.

In initial screenings the film was seven and a half hours long, divided into four parts. The version of La roue on this disc is a restored 273 minutes -- four and a half hours. Most silent movie fans have seen only far shorter versions prepared for American distribution. The restoration is by the experienced Eric Lange and David Shepard, and the monumental music score is by Robert Israel.

Watching La roue is a heightened experience. It's definitely a silent movie in some of its acting style, but Gance's progressive direction does much more than simply record the action. The interior décor of Sisif's house is forever changing, with Elie working on his special violin varnish and Sisif constructing models of his inventions; the lighting effects through the windows are carefully observed, with trains passing and the time of day changing. Gance's close-ups are more organic to the action. He doesn't use then standard 'cameo' vignettes, and often frames faces in extreme angles with dramatic lighting.

Gance uses visual effects to express psychological concepts. When Sisif has his fortune told, a view of trains are superimposed into the palm of his hand. Norma's face appears reflected in windows and hovers in space when the men in the story think of her. We know that Sisif's obsession with the young girl has gone too far when he can't erase her phantom image, even after drawing a curtain over a window.

Even more successful are Gance's poetic effects. We've all seen D.W. Griffith's use of symbolic shots, like the "endlessly rocking cradle" in Intolerance. Gance organizes his entire movie around the visual motif of the wheel, using images of railroad machinery. A view of the tracks below a moving train narrows to isolate a single rail, the lifeline of Sisif's existence. Superimposures express Sisif's identification with his beloved locomotive. Part One ends with a dramatic shot on the switching yard's massive locomotive turntable. Sisif stands at the center of the rotation, regarding the camera as the various rails turn around him. Which track shall he choose and what direction will his life take now?

The most celebrated aspect of La roue is Abel Gance's dynamic editing. He intensifies parallel cutting between two or more contrasting images by decreasing the duration of individual shots, until the screen pulses with frantic flutter cuts. Emotional faces and furiously turning train wheels share the same electrified moment. We're informed that the similar cutting found in Sergei Eisenstein's heralded Soviet films were directly modeled on Gance's experiments. Quotes from Akira Kurosawa and Jean Cocteau indicate that Gance's experimental editing impressed and influenced progressive film artists everywhere.

La roue has plenty of overheated melodrama. Sisif hardens into a bull-like madman over the "Rose of the Rails" that cannot be his. He blocks the potential happiness of his children, allowing the selfish De Hersan to take the initiative. In the first half of part two the family truth finally comes out in the open. Sisif and Elie are living at the end of a funicular rail line on a lonely mountaintop; when Norma and De Hersan reappear, the only possible resolution is disaster. Gance's imagery now turns to nature, and the 'wheel of life' takes over from the mechanized wheels of industry. The remarkably moving ending unites all of Gance's visual themes. Young people form a circle to dance on a mountain meadow. Superimposed over the mountain peaks, a negative image of Sisif's locomotive conjures a vision of a soul in migration.

At 4.5 hours, La roue is best watched in two sittings. Séverin-Mars is a powerful presence, perhaps the first 'railroad hero' in a tradition of French classics made by artists like Jean Renoir and René Clément. Dramatic close-ups show the actor's face looking like a piece of oiled granite, with artistic lighting we don't expect in a movie from 1923. Ivy Close's Norma begins the film as an idealized virginal earth-spirit no different from those in early silents by Griffith and Chaplin. She plays with goats and dances in the soot and grime of the switching yard. But by part two Norma has changed into a much more complicated character. Trapped in a bad marriage, she watches helplessly as the men she loves destroy themselves for her sake.

La roue is a genuine classic. It overpowers us with freshly minted cinematic devices, yet maintains a dramatic balance throughout. It confirmed Abel Gance as a leading artist in a new art form. He'd stay at the top of his form until the beginning of sound.

Flicker Alley and Blackhawk's DVD of La roue is an unqualified labor of love. The film's two halves are presented on separate discs. Picture quality is very good in general and excellent when compared to most other surviving films of this vintage, with a good grayscale and better than average sharpness. Even better, the image remains steady, even across splices. The insert booklet explains that the longer show had to be pieced together from material from various French and Russian versions. Two brief but important scenes were rescued from an old 9.5 home movie version, and are of lesser quality. The film uses inter-titles but also has many titles superimposed over images.

Of special interest is a promotional short subject emphasizing the film's 'genius' director. Gance is shown working with his cameramen on dangerous-looking moving trains. He's the very picture of the artist engrossed in his art.

The insert booklet contains a fascinating essay by William A. Drew. It details the filming in Nice and the French Alps, quoting actress Ivy Close and others. The set for Sisif's house was built between two railroad tracks, necessitating the use of guards to prevent cast and crew from walking into the path of passing trains. Gance filmed much of the picture night-for-night and kept his cameramen forever busy working out new lighting plans and in-the-camera special effects. Gance's beloved Ida Danis fell ill with tuberculosis, and the film's move to a mountain location was partly motivated by her doctor's advice. She was sick all through the production and died just as editing was completed. Drew's essay is especially good when expressing La roue's significance to the development of film art.

Robert Israel contributes an essay on the creation of his musical score for this restoration. The disc set rounds out with a gallery showing the film's full original screening program.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

La roue rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Contemporary promotional film, original program

Packaging: Two discs in keep case

Reviewed: April 22, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |