| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

The Thief of Bagdad |

|

The Thief of Bagdad Criterion 431 1940 / Color / 1:33 flat full frame / 106 min. / Street Date May 27, 2008 / 39.95 Starring Conrad Veidt, Sabu, June Duprez, John Justin, Rex Ingram, Miles Malleson, Morton Selten, Mary Morris, Adelaide Hall Cinematography Georges Périnal Production Designer Vincent Korda Art Directors Ferdinand Bellan, W. Percy Day, William Cameron Menzies, Frederick Pusey Special Effects Lawrence W. Butler, Tom Howard, Peter Ellenshaw, Wally Veevers Film Editors William Hornbeck, Charles Crichton Original Music Miklós Rózsa (Lyrics: Robert Denham) Written by Lajos Biró and Miles Malleson Produced by Alexander Korda, Zoltan Korda, William Cameron Menzies Directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, Tim Whelan |

Criterion is slowly releasing all of the great films of Michael Powell, and this month brings us the undisputed favorite of all Arabian Nights fantasies, in a colorful presentation that improves on the MGM disc from 2002. Filmed just as WW2 was overtaking England, this Alexander Korda Super Production was the special effects benchmark of its day - its poetic script and imaginative design have been much imitated but never bettered.

A visual and sonic swirl of 1001 delights, The Thief of Bagdad is not a remake of the silent Fairbanks film but an entire rewrite from the pen of Miles Malleson, who we know better as a familiar character actor in dozens of English classics. Malleson's flair for whimsy and fairytale poetry is unparalleled; his dialogue is inspired. The purity of the Prince and Princess transcends their love talk; their meeting is an inspired expression of the simplicity and magic of Love. The Forbidden Garden where they rendezvous is a metaphor for forbidden carnal knowledge, and they truly meet as lovers do, each the dream fantasy of the other. Informed with tidings of certain death, this meeting is no Disney version of True Love: Malleson even salts Ahmed's deception with a wry wit: "Very good genii are just as tiresome as very good men."

The mechanics of absolute power are made clear with 1/10th the effort of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen - the Sultan (Malleson himself) is a vain fuddy-duddy more concerned with toys than ruling wisely. He loves his daughter but is easily cajoled into trading her for a magical mechanical horse. Jaffar is perhaps the best villain ever in a fantasy film, a cagey, charming schemer. Jaffar relates to the world only through conspiracy and murder, yet has a completely understandable desire to be loved. Cruelty is a given in this world of despots and the downtrodden. Executions are a daily ritual and death is mandated for the simplest crime, even just looking at the Princess as she passes in the street.

The magical realm remains wondrous after repeated viewings. This fantasy world isn't ruled by gods or demons but simply inhabited by the occasional fantastic being, like Rex Ingram's towering, bellowing Genie. He has his own perspective on the workings of the world and is quite happy to dispense wisdom to Abu, even while preparing to crush him underfoot. Out-conned by the tiny thief, the Genie likewise yearns for his own emancipation: "Free! Free! FREE!"

Played with a direct enthusiasm, Sabu's young beggar thief is a wonderful package of conflicting ideas - loyalty, ambition and a desire for adventure. Like everyone else in the picture Abu struggles to find his destiny, and succeeds by placing the problems of others ahead of his own. Clad in just a sash and armed only with a knife, Abu has the courage to face the unknown and combat creatures no man has seen. He outsmarts a monster spider in its own lair and puts himself in the first rank of thieves by stealing the sacred object of a remote civilization. The maturity of The Thief of Bagdad lies in its lack of dull moralizing: the world is full of thieves of all kinds, and the story sees no harm in the enterprise of the dispossessed. A mischievous chapter finds Abu lost in a far land of old wise men. He's given all the tools he needs to defeat Evil, except a way to get back to Bagdad in time to forestall a dreaded execution. A magic carpet stands ready to transport Abu, yet the wise gentlemen who have been so kind to the boy have expressly forbidden him to take it. ...

Some of Alexander Korda's movies have dated but from a production standpoint most equal or better work being done in the United States at the time. The Thief of Bagdad is a visual feast and a musical delight. A battery of great designers, including William Cameron Menzies, contributed to the clean sets and exotic costumes.

Several large forced-perspective Bagdad cityscapes are breathtaking elaborations on storybook illustrations. The aforementioned Forbidden Garden, with its serene pastels, is the equal of anything in the sometimes gaudy The Wizard of Oz. The Sultan's palace is a colossal expanse of waxed floors and vaulted ceilings.

In terms of design, the special effects are superior to much work being done today. Instead of our present ethic of convincing through sensory overload, the fantastic settings, characters and action of The Thief of Bagdad are simplicity made real. Conrad Veidt's menacing gestures are enhanced by having a 'shadow man' mimic his movements, so as to throw a perfect silhouette on the wall behind him. Miniatures are used for ships. A giant canyon is effectively reproduced in miniature, with more than one segue between live action and miniature settings brilliantly achieved.

By not having to be strictly realistic, the effects transcend their sometimes-primitive means. The Technicolor traveling mattes have massive blue fringing, but it must be remembered that even if the appropriate film stocks for mattes and counter-mattes existed in 1940, war shortages probably wouldn't allow labs to do special work for just one film. In Technicolor such effects required not three but nine times the effort. Lawrence Butler and his team from Things to Come do marvelous work with the interaction with the genie, the mountaintop temple, etc. With the added resolution of DVD, the wires used to suspend the magic carpet are clearly visible. Yet the spirit of the story makes such details irrelevant to the enjoyment at hand.

The Thief of Bagdad was finished in Hollywood when war broke out. I don't have the research available to pinpoint the exact contributions of its three credited directors. According to the IMDB, there are three more uncredited directors: Alexander & Zoltan Korda, and William Cameron Menzies. The multi-armed Silver Maid reminds us of the strange wonders of later Michael Powell fantasies, but I'm not familiar with what sections he directed, beyond Abu's first meeting with the Genie. 1

Finally, the film score of Miklós Rózsa is probably his best, and one of the finest in film history. It provides the soul and spirit of every sequence, expressing the purity of the young lovers and the forcefulness (and unrequited love) of Jaffar. A rousing chorus explains the joy of seafaring that Abu yearns to experience, and Abu's essential playfulness is communicated by a ditty he sings to bolster his courage: "I want to be a bandit, can't you understand it?" The tone of Rózsa's magisterial main theme has been revisited time and again, for films like Ivanhoe and Ben-Hur. 2

The IMDB says that Glynis Johns and Cleo Laine are somewhere among the film's bit players.

Criterion's 2-disc The Thief of Bagdad is an improvement over MGM's 2002 budget-priced release. That disc had a good-looking picture but its track was heavily compressed and distorted. A few isolated shots in this new encoding have Technicolor registration problems, and the same light grain is visible overall, but this is still the first really satisfying home video presentation of this title.

Karen Stetler remains Criterion's disc producer for the movies of Michael Powell, and she assembles a satisfying collection of extras for this vintage classic. The feature has two commentaries, one with Francis Ford Coppola & Martin Scorsese and a second with historian Bruce Eder. Scorsese identifies the first scene as having been directed by Michael Powell and continues to analyze the picture from a Powell-centric position, acknowledging that many hands were involved in its manufacture. Coppola's comments are more subjective; it was a childhood favorite. He gives us an audio extra by humming all the main musical themes!

Of special note is an isolated music and effects track that makes the disc set into a de facto original soundtrack album, or a dialogue- free operetta. The new featurette Visual Effects allows Ray Harryhausen, Dennis Muren and Craig Barron to analyze the film's innovative effects techniques. It becomes a bit long and unfocused when the experts stop talking shop and relate their personal feelings about the movie. An animated sidebar spells out the steps in the blue screen traveling matte process, an innovation pioneered by the film.

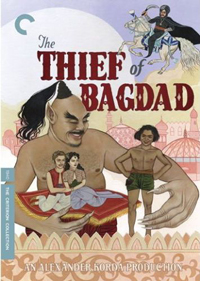

The second disc contains The Lion Has Wings, a 1940 propaganda feature filmed when the war forced The Thief of Bagdad into hiatus. Also included are original Michael Powell audio dictations for his autobiography, a radio interview with Miklos Rozsa, a still gallery and a trailer. The insert booklet contains essays by Andrew Moore and Ian Christie. The cover illustration may not be pretty, but it's authentic and models the designs for the original UK ads for this film

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

The Thief of Bagdad rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent -

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Commentary with Francis Ford Coppola & Martin Scorsese, Commentary with Bruce Eder, Music and Effects Track, Trailer, featurette Visual Effects, 1940 propaganda feature The Lion Has Wings, Michael Powell audio dictations, radio interview Miklos Rozsa, still gallery, essays by Andrew Moore and Ian Christie

Packaging: 2 discs in keep case

Reviewed: May 9, 2008

Footnotes:

1. A good true story bears repeating. I worked on the short-lived Zoetrope lot in Hollywood in 1980, when Coppola had Europeans like Jean-Luc Godard and Michael Powell on the payroll as 'geniuses in residence' to advise and commune. I never saw either, but pal Rocco Gioffre did run into Powell in an elevator and described him as a small, genial man with rosy cheeks, who actually started humming Abu's ditty from The Thief of Bagdad!

Return

2. Ray Harryhausen's first love was fantasy, not Science Fiction. The 7th Voyage of Sinbad has some of the simplicity of The Thief of Bagdad, and Bernard Herrmann's score certainly supplies the grandeur. But like most other Arabian fantasies, the later The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, even with its handsome Rózsa score, is just a cheap carbon of this original.

Return

3. (A response letter from author Avie Hern, 11.21.02):

Dear Glenn: Really enjoyed your reviews of two of my favorite films, The Thief of Bagdad and Sunset Boulevard, but feel compelled to add a few thoughts and make a few corrections.

The Thief review is particularly well done and incisive, analyzing character and bringing little-mentioned aspects of the film into perspective. A couple of points of fact need to be made, however:

The lyrics to the film's songs (another song, an imperious patter-rant for the Djinni, was written and recorded by Rex Ingram and orchestra, but was cut; I have a very poor tape of it from a 1940 BBC broadcast) were actually written by Sir Robert Vansittart (pronounced Van-SITT-art), whose "day job" was the Number Two man in Britain's Foreign Office (he was desperately trying to avert war with Germany while collaborating with Miklos Rozsa on the songs in the evening). As Rozsa pointed out, the British public probably wasn't ready to hear that one of their most important diplomats was moonlighting as a lyricist for Alexander Korda (though no less than Winston Churchill also collaborated with his friend, Alex Korda, with Korda serving as a secret courier between London and Washington during World War II). It's no surprise, then, that Vansittart would choose the pseudonym "Robert Denham"; in fact after war's end, King George VI made him Lord Vansittart, First Lord Denham (the district where Korda had his studio).

Second: While Thief's special effects obviously required a large team to pull off, their design and success are generally credited to expert Ned Mann, whom Korda imported from Hollywood for the production.

Third: The film's production was, indeed, moved from London to Hollywood after the outbreak of World War II (the reason why Miklos Rozsa became a "Hollywood" composer, when he decided to remain here after Korda returned to Europe after the war. Rozsa was in fact introduced to his future wife actress Margaret Finlason by June Duprez, who played the Princess). If you look at the scene in the Princess's garden in which she's surrounded by her ladies-in-waiting, you can see that the large swing in which she's lounging changes subtly from shot to shot: in some shots it has mirrored sides, in others it does not. It seems fairly obvious that Korda decided to pack up his production while that scene was being photographed, with a not-quite-duplicate swing reconstructed in Hollywood to finish the shooting.

You point out quite correctly that the film has as many as six directors, with only three credited. As much as I love the film, one of its failings is that the guidance of so many hands results in a somewhat choppy feel, which is only exacerbated by the fact that, Miles Malleson's obviously wonderful dialogue aside, a lot of the film's loose structure is shoehorned into a preconceived notion of what Korda wanted the movie to be -- many incidents and scenes lack the sort of compelling inevitability that a well-conceived, well-structured film has, and are only there for the convenience of Thief's showpiece elements.

The above paragraph is why my estimation of The Thief of Bagdad has fallen a bit as the years go by, while my regard for Korda's The Four Feathers has grown. The latter manages to be a slyly incisive commentary on the glories and pitfalls of empire building and colonialism, while never losing sight that it must sell itself as a spectacular adventure tale (at which it succeeds superbly). It's in obviously stark contrast to this year's version, which failed specifically because it condemns the characters the audience needs to root for, and strips the adventure tale of every last vestige of that crucial commodity. A first-rate DVD of this title is essential; if you know of any plans afoot to release one, I'd be grateful if you'd let me know.

Thanks for the thoughtful commentary. As I've said in the past, I'm appreciative of the nice words you've had for my talent bios and liner notes on Anchor Bay product (boy, would I like to work on titles I really care about, like the above...) Sincerely, Avie Hern

Return

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |