| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

Emile de Antonio: |

|

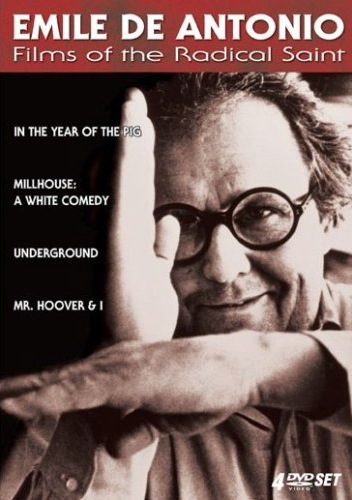

Emile de Antonio: Films of a Radical Saint In the Year of the Pig, Millhouse: A White Comedy, Underground, Mr. Hoover and I Home Vision Entertainment 1968 - 1989 / B&W & Color / 1:78 anamorphic widescreen and 1:37 flat full frame / 6 hours, 8 min. / Street Date June 17, 2008 / 59.98 Directed by Emile de Antonio |

Labeling Emile de Antonio as a radical filmmaker sounds like a way of slotting him into a convenient pigeonhole, until we hear the genial man referring to himself with the exact same phrase. In the 1960s, De Antonio marshaled the newly appreciated power of film by buying some 200 hours of old 1954 TV kinescopes from CBS for $50,000. It was the entire TV coverage of the Army-McCarthy hearings. Because it was "no longer of interest", CBS was considering tossing it all into an incinerator. De Antonio fashioned the old film into his 1964 feature film Point of Order. The irreplaceable documentary stands as key evidence against those who would insist that Senator McCarthy was a patriot brought down by a leftist conspiracy.

Emile de Antonio: Films of a Radical Saint gathers four of De Antonio's later, even more controversial docus. They played in New York and in college towns, when they weren't effectively banned by the government, as De Antonio claims was the case with Millhouse: A White Comedy. All are essential to any serious study of documentary film.

1968's In the Year of the Pig assembles prime news film to tell the story of Vietnam in the 20th century. It was practically the only record available of the historical reality of Southeast Asia at a time when Americans were bombarded daily with rhetoric about Freedom and the Communist threat. Avoiding an imposed narration, De Antonio simply stacks newsreel and archive footage behind some very good interviews with people like Daniel Berrigan and the late David Halberstam. The footage delineates the efforts of French colonialists to retake control of Vietnam after WW2, and with the help of the United States, suppress the country's attempts to re-unite. When America takes the leading role in the late 1950s the news film shows a succession of puppet tyrants placed in power. Advisors become fighting troops and a faked attack in the Gulf of Tonkin is used as the lever to get America fully involved.

De Antonio obviously guides the footage, playing La Marseillaise on Vietnamese instruments as the defeated French quit the country. The show begins with an electronic audio montage of helicopter rotors that may have been the inspiration for the opening of Apocalypse Now. The docu underplays President Kennedy's role in the Vietnam disaster, but the images we see of Eisenhower, Johnson and Nixon are highly unflattering. Much of the footage is surprisingly effective, even forty years later. A witness describes the awful spectacle of a Vietnamese monk immolating himself, and then the highly visible Madame Nhu brazenly states that the monks were paid to burn themselves, incited by foreign influences. It's interesting to see personalities like Gerald Ford making grave pronouncements about developments in Vietnam, while Kennedy-era appointees like Robert McNamara visit the country. Lyndon Johnson's sober pledge for 'no wider war' seems so sincere that we have to wonder what exactly mandated the major combat commitment that began in 1965.

The film shows footage of North Vietnam's defenses and the way its entire population is enlisted in the war effort, which in 1968 was considered by many to be subversive propaganda giving comfort to the enemy. In his commentary De Antonio claims that some theaters attempting to show the film were intimidated by vandalism and death threats.

In the Year of the Pig was heavy-duty campus screening fare in the late 1960s. Emile de Antonio again showed great ingenuity in gaining access to controversial news film. It now plays as priceless found footage, a record of history that would otherwise be lost -- or suppressed. Network news of later decades, such as coverage of the First Gulf War, is now tightly controlled corporate property.

Millhouse: A White Comedy was intended as mirthful character assassination, on the principle that one can't be too unkind to Richard Nixon. De Antonio doesn't need to distort a thing, as a simple collection of news film reveals Nixon to be a consummate dirty politician. Nixon gets elected to the congress by spreading rumors that his opponent Jerry Voorhis is "soft on Communism." He then leaps to the Senate by smearing opponent Helen Gahagan Douglas as a "pinko", distributing her voting record printed on pink paper. Nixon's major career move comes when he turns the investigation of accused spy Alger Hiss into a media event. Millhouse (which purposely misspells Nixon's middle name) resurrected the Vice Presidential candidate's controversial "Checkers" speech, in which he sidestepped accusations of special backing by large companies by offering an absurd and irrelevant "heartfelt" appeal to the American people.

We see Nixon's motorcade attacked by South Americans during a goodwill tour. He gets chummy with puppet rulers in Vietnam and performs his awkward early exit from politics after a failed Californian Gubernatorial bid. His supposed farewell is a near-psychotic speech that finishes with a bitter, "You won't have Nixon to kick around any more." At a 1968 rally, he assures his audience that Hubert Humphrey is really a radical. Elected on the promise to get America out of Vietnam, Nixon instead insists that the U.S. will leave Vietnam only with honor, and the bombs start falling.

Millhouse is a personal attack, undeniably. It begins with the installation of a (really bad) likeness of the President in a wax museum. Pat Nixon stares like a zombie at most public appearances, while the presidential daughters often look unhappy or uncomfortable. Nixon sweats behind microphones and avoids Q&A sessions in favor of a rigged meet-the-voters TV show complete with signs that ask the studio audience to applaud. Bob Hope entertains a political dinner with jokes about homosexuals, and a gyrating go-go dancer makes Nixon uncomfortable by dancing about two feet from his nose. A White House reception uses Marine Corps musicians to provide a brass fanfare more appropriate for the entrance of a Roman Emperor. Finally, as Nixon claims that America has no plans to exploit Vietnam or place permanent military bases there, De Antonio scrolls an endless list of American corporations that have already begun business in Saigon.

Underground, from the Bicentennial year, is a departure from Emile de Antonio's previous works. It uses pieces of older documentaries but focuses mainly on a filmed interview with actual Weather Underground fugitives, public enemies high on the FBI's most wanted list. The nation's law apparatus was unable to locate the SDS splinter group that had carried on a campaign of anti-government bombings in the early 1970s in the hopes of igniting a revolution. See Savant's review of the documentary The Weather Underground for more detail.

De Antonio reports that he had little difficulty contacting the radicals-in-hiding. Along with cameraman Haskell Wexler and editor Mary Lampson, he filmed the interview in a California safe house, avoiding his subjects' faces by filming them through sheets and from behind. One camera angle used by De Antonio became a hot topic of discussion among film students. The Weathermen and women are filmed through a mirror. We see De Antonio, Lampson and Wexler with his camera staring right at us, but only the backs of the subjects' heads. The angle states exactly how the film was made and acknowledges the presence of a camera at all times. What's more, it suggests that the filmmakers are an active part of the testimony, and not separate from it. To some the shot suggests solidarity with the Weathermen. Others see it as a challenge to the F.B.I.: we're exercising our First Amendment rights and we're not hiding from anybody.

Underground disturbs not because it allows the Weathermen to state their case, but because De Antonio adds his own documentary editorializing that implies approval and collaboration. Actually, the Weather Underground almost single-handedly killed off the legitimate anti-war and anti-government protests of the 1960s. Considering the grief their violent activities caused for their victims and their own cause, the Underground doesn't occupy a very sympathetic page in history. Conservatives still use their example to equate patriotic activism with terrorism. Being daring outlaws in the eyes of America sounds great in a Jefferson Airplane song. But the Weathermen characterize the bombings that killed people as innocent mistakes, evading responsibility just as do the power elite they wish to bring down. Reporting on wanted fugitives is protected free speech, but it is disturbing to see De Antonio flashing friendly smiles at his subjects. Underground comes off as endorsing more than just the Weathermen's idealism. Is the film a grand experiment testing the limits of film journalism, or just plain irresponsible?

De Antonio makes himself the subject of Mr. Hoover and I. The director addresses the camera directly, telling us that J. Edgar Hoover is the most villainous American in history and the renegade leader of an out-of-control secret police force. De Antonio recounts his experience applying for his own F.B.I. record with the Freedom of Information Act. The F.B.I. used bureaucratic dodging to avoid complying with that law. An informant told De Antonio that his sensitive files were surreptitiously placed with those of one of the Weathermen, to keep him from accessing them. One letter that Hoover didn't want released requests that, in the case of a "national emergency", Emile de Antonio be considered for "custodial detention" -- an evasive euphemism for imprisonment in a concentration camp.

We see De Antonio at a campus speaking engagement, talking with John Cage while the musician bakes bread, and getting his hair cut by his wife. It's here that De Antonio proudly calls himself a Communist and a radical, and says that he loves his country and simply wants to make it better, as opposed to politicians who want careers. He talks about his movies going unseen because of threats (vandals painted the word "Traitor" on a screen in California) and feels that the Nixon administration saw to it that corporate-owned theaters wouldn't play Millhouse. He also comes off as something of a conspiracy buff in regards to the JFK assassination, in reference to his film Rush to Judgment. Like Underground, Mr Hoover and I ends with a simple statement of political idealism. The director is a sincere and likeable speaker, but we can't help but feel that his earlier documentaries using mostly unaltered historical footage are much more persuasive.

Distributed by Image, Home Vision's four-disc DVD set of Emile de Antonio: Films of a Radical Saint is a welcome release. All four features are transferred in fine condition, and the only time that the quality drops is in the poorest of the kinescope sources. Just the same, the infamous Checkers speech (included uncut separately) is the best I've seen it on film or video. In the Year of the Pig has a full director commentary and a vintage TV interview with De Antonio. Millhouse carries the Checkers speech and an excellent interview from a TV show called Alternative Views. Underground has an even more interesting Alternative Views interview. An insert booklet contains fine essays by Dan Streible, Jonathan Kahana. Jonathan Rosenbaum offers a spirited defense of Mr. Hoover and I.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Emile de Antonio: Films of a Radical Saint rates:

Movies: Pig: Excellent, Millhouse: Excellent, Underground: Very Good, Hoover: Good

Video: Excellent

Sound: Exellent

Supplements: Interviews, commentary, see above

Packaging: Four discs in fat keep case

Reviewed: July 9, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |