| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

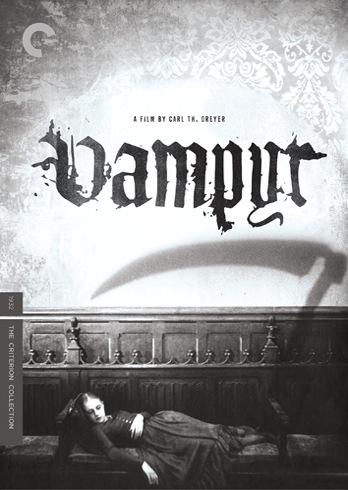

Vampyr |

|

Vampyr Criterion 437 1932 / B&W / 1:19.1 flat full frame / 73 min. / The Strange Adventure of David Gray / Street Date July 22, 2008 / 39.95 Starring Julian West, Maurice Schutz, Rena Mandel, Sybille Schmitz, Jan Hieronimko, Henriette Gérard Cinematography Rudolph Maté Art Direction Hermann Warm Film Editor Tonka Taldy Original Music Wolfgang Zeller Written by Carl Theodor Dreyer, Christen Jul from In a Glass Darkly by Sheridan Le Fanu Produced by Carl Theodor Dreyer, Julian West Directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer |

Film horror has been riding high in recent years. We're just wound up a couple of seasons of gore-horrors based on the theme of torture. Before that were the much different "J-Horror" pictures, modern ghost stories from Japan that generated much of their sense of dread from dreamlike, menacing imagery. And a few years before that we withstood a wave of self-aware slasher films, featuring teenagers that try to survive bloody murder by applying lessons learned from earlier horror movies like Halloween.

Back in the early 1930s before Universal's Frankenstein and Dracula there really was no established horror genre. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Nosferatu are highly original, artistic silent films that were soon recognized as classics. Just as impressive but much more obscure is Carl Theodor Dreyer's 1932 Vampyr. An early German talkie basically stylized as a silent, Dreyer's film creates a surreal mental space reminiscent of Jean Cocteau.

European audiences didn't go for Vampyr, and for decades it became a difficult movie to see. 16mm prints that circulated in film schools were pieced together from incomplete French and German versions, with terrible audio quality and unwanted burned-in subtitles. Until now, the best version available was on an Image disc. Most of the film seemed to be intact but the importer had to obscure half the frame with black boxes to cover up unwanted European subtitles.

Criterion's revelatory 2-disc DVD set is based on a 1998 restoration by Martin Koerber and the Cineteca di Bologna. What was once a confusing puzzle can now be seen as a new direction for the horror film, a slow moving hallucination filled with bizarre visuals. Vampyr locates the uncanny not in the dark but in pale, powdery whiteness signifying the absence of life-giving blood.

Older copies of Vampyr were practically unwatchable. The fragments remaining seemed to be an almost random sequence of creepy, meaningless scenes. This nearly intact restoration reveals Vampyr as a conventional vampire tale, but one in which waking reality has been warped by eerie, subjective visions. Audience surrogate Allan Gray joins a household petrified with fright. A simple stroll reveals the neighborhood to be infested with ghostly demons. They manifest as disembodied shadows walking along paths in the woods, and dancing in an empty factory. Allan peers through doors and windows, observing phantom characters. He sees the shadow of a peg-legged man "rejoining" its owner.

Other visions are not directly observed by Allan. A skeletal hand offers a vial of poison: is it "really" happening, or is it a subjective illusion? Or is it a poetic expression of the menace of suicide? The movie is a series of evocative, frightening visions. A Death-like reaper waits at a river crossing. Allan finds the night-gowned Léone draped across a bench amid the trees. Gisèle stands tied to a bed-frame, waiting to be sacrificed to the ancient vampire woman. Many of these visions resemble classical paintings and tapestries with macabre themes. Rudolph Maté's camera creeps through white rooms and stages a killing under tons of choking white flour. "Whiteness" is Dreyer's signifier of death.

Vampyr is loosely adapted from Sheridan Le Fanu's Carmilla, the story source used for Roger Vadim's Et mourir de plaisir and Hammer's The Vampire Lovers. Although probably considered shocking in 1932, there are no direct vampire attacks, no nudity or overt sexuality. But we do get the image of Sybille Schmidt, a vampire's victim turned predator, leering upward at her sister in demonic bloodlust. The stare is unnervingly direct, and enough to make sensitive people nervous. Léone's perverse expression also suggests the lesbianism implied in the Le Fanu novella. Léone's delight in malice effectively undermines the foundation of this puritanical moral tale -- her lustful grin is undiluted Evil.

The film's centerpiece forces Allan Grey to experience his own death. He lies in a coffin, eyes open, as the lid is screwed tight; the ancient vampire woman appears in a window over his face. Allan's subjective view shows us ceilings and doorways passing by as the coffin is carried to the grave. It's a truly unnerving experience, repeated but not bettered in films like The Horrible Dr. Hichcock and Alfred Hitchcock's 1955 TV episode Breakdown.

Like most of what happens in Vampyr, the coffin scene is only half-explained. Dreyer's camera prowls through a ruined factory littered with odd objects, while Wolfgang Zeller's insistent music strikes nervous chords. An opening door may reveal the melancholy head of the household, or a weird shriveled man with disturbingly recessed eyes. Story exposition is communicated with silent-style title cards and pages of a book about vampires. Little overt Christian symbolism survives into the final cut, but the ending is a pastoral "walk into the light" that reminds us of the Ave Maria conclusion to Disney's Fantasia. Dreyer reportedly intended Vampyr to be a commercial comeback after the financial disaster of The Passion of Joan of Arc. We're told that most 1932 audiences dismissed the weird story and purposely vacant hero as the marks of incompetent filmmaking.

For horror fans, the thrill of Vampyr is watching a genre come to life before our eyes: some of the best horror films are abstract obscurities, like John Parker's poetic Dementia / Daughter of Horror. Allan Gray experiences a surreal demonic playground that looks forward to the haunted hosts of horror delicacies like Carnival of Souls and Lemora, A Child's Tale of the Supernatural. Roman Polanski adapted themes and visuals from Vampyr for his 1967 fairy-tale horror "spoof" The Fearless Vampire Killers. Polanski's old professor is a dead ringer for Dreyer's villainous doctor, while the innkeeper's stout wife is a good match for the maid in this film. Both films feature artwork that depicts skeletons preying upon the living, and Polanski replays some of the Dreyer's odd camera tricks. We think we're watching Allan's view as he examines some half-built coffins, but a fast pan reveals the young hero disappearing down a corridor ...

Repetition has weakened some of the visuals of the J-Horror films -- evil children with long hair obscuring their faces -- but they definitely carry on Vampyr's basic design. The world is unstable and menacing and strange powers are at work just beyond our peripheral vision. Before the psychological and visceral revolutions of the 1960's and 1970's, artful horror could be a matter of quiet, disturbing moods. Vampyr shows us the origins of the Uncanny.

Criterion's DVD of Vampyr is given special attention by disc producer Issa Clubb. The transfer is good but naturally not perfect; the 1998 restoration could find no original elements and pieced the picture together from surviving German and French materials. The image is always steady but often grainy and slightly scratched. It's still far better than earlier video versions. I don't think I've seen the German title sequence before, and this is the first time that the crude early-talkie audio track has been in anything like listenable condition. Wolfgang Zeller's scary music is just well enough preserved to give the soundtrack some real power.

Film scholar Tony Rayns' detailed commentary attributes the occasional story discontinuities to missing scenes. For ease of viewing, an alternate encoding of the film substitutes English inter-titles and book pages for the German originals. The second disc presents a long-form Danish documentary on Dreyer's fitful directing career, focusing on the reception of his last film, Gertrud. Casper Tyberg narrates a "visual essay" on Vampyr, comparing Dreyer's style with themes in classical paintings and using rare photographs to describe cut episodes. Dreyer speaks in English on a 1958 radio show, explaining his theories of filmmaking.

An insert booklet contains essays by Mark Le Fanu and Kim Newman as well as a 1964 interview with star and producer Julian West (= Baron Nicolas de Gunzburg). Filling out the fat box is a specially published 214-page book containing Dreyer's film script and the original Le Fanu novella Carmilla. Horror fans have been bemoaning the lack of a watchable Vampyr for decades, and Criterion's new DVD more than fulfills their wishes.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Vampyr rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Very Good

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Commentary by Tony Rayns, Alternate texted version, Dreyer documentary, Visual Essay by Casper Tyberg, Dreyer radio broadcast, essays by Mark Le Fanu & Kim Newman, interview with Nicolas de Gunzburg, Dreyer's complete original script, the full novella Carmilla

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: July 13, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |