What Ever Happened to

Great Fight Scenes?

A Dissenting Opinion about

Bigger and Better Action Movies

By Glenn Erickson

Looking for a good screen fight in the latest action spectacles has become a frustrating experience. Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight repeats the pattern of his Batman Begins, producing fight scenes composed of little more than a few fast shots where we can't see what's really happening. Instead of pulling back to display the action, the camera pushes in tight, producing shots that look like a close-up of an electric blender at work. Considering the fact that Batman almost never loses, it might make sense to turn his combats into blurred impressions, but it's a bit frustrating not to see what makes the Caped Crusader always come out on top. I mean, how effective can his exalted fighting skills be, when he wears a mask that makes turning his head so difficult? The Batman series is heavily stylized comic book entertainment, so we shouldn't expect strict realism.

Most of last years' The Bourne Ultimatum is a prolonged chase scene. Paul Greengrass and editor Christopher Rouse's editing is so absurdly fractured, we must pay rapt attention just to follow ordinary actions. When Bourne encounters an adversary in a narrow airport corridor, the already jarring cutting pattern becomes a kinetic pinwheel. Bourne delivers five crushing blows (listen to that soundtrack!) in the space of two or three seconds, and goes on his way. The audience must concentrate so hard to comprehend the action, that it has no time or energy left to critique the action.

If you slow down Ultimatum to examine the corridor fight, you'll discover that what happens is almost ridiculously simple. There's no particular reason why Bourne should so easily defeat his opponent. There's nothing special about the camera angles or the direction, except that it purposely avoids clarity. The editiorial chop suey technique does all the work. The fights in Ultimatum are the equivalent of the dances in Chicago, where every musical number is splintered into so many shots, we can't really tell if the performers can dance. With all the close-ups, we can't be sure if the legs on view even belong to the star talent. A flashy presentation covers up a mediocre action performance.

Critics bemoaning the state of movies used to put the blame on MTV, with its emphasis on surface flash over substance. Today's action movies appear to be competing with video games in both content and pace: Bourne Ultimatum is a big-screen video game with a minimal plot. Secondary influences are important as well -- Asian martial arts films, comic books. Remember the way a Jean-Claude van Damme movie would suddenly go into cheapo slow-motion mode, created by taking an ordinary action shot and step-printing every frame four times? The Matrix's fancy ultra slow motion trick effect refined that idea with dozens of digital still cameras, stopping the show for us to admire Keanu Reeves tumbling endlessly through the frame in his leather greatcoat. For the brief time that particular gag was in vogue, it turned fight scenes into superhero comic book panels, slowing the action into graceful dynamic still poses. 1

Video game cutting creates fights that happen in a dramatic vacuum. The editing is the subject, not the characters or the story. If we get involved, it's because we're playing out a pre-existing fantasy (Batman - yay!) or responding to the audio montage. Note that modern screen fights haven't evolved much farther than the punch-outs in old Republic Serials. Instead of the bad guy taking a series of exaggerated haymakers, the sound effects and editing tell us which blows are having a maximum effect. If the punches come on so fast that our brains can't process them, then it must be a really exciting fight scene! But the technique makes performance irrelevant. With the magic of fast cutting and wire removal, anybody can be Jackie Chan. I see most new action movies as ultimately less-thrilling, because of their interchangeable fight scenes. When a "Quisinart montage" fight begins, I begin to tune out.

Just like the best western shoot-outs and the most exciting car chases, classic movie fights are as indelible as great acting scenes. Only one or two of the examples that follow might qualify for a "Best Screen Fights of All Time" list; a couple of them aren't even fights. But they display qualities that have mostly disappeared from today's screen action.

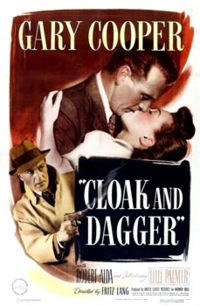

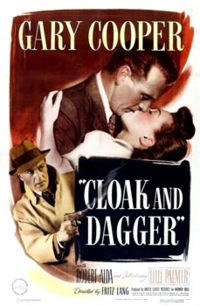

1. Fritz Lang's Cloak and Dagger (1946) is an almost forgotten spy movie that might have been a classic, if its producers hadn't jettisoned its entire last reel warning about future uses of the atom bomb. Its one sustained fight scene is a killer. Gary Cooper ambushes an Italian agent (Marc Lawrence) in the empty lobby of a rooming house, and their fighting gets really dirty. Lawrence tries to gouge out Cooper's eyes. Cooper gets Lawrence into an arm lock and then gives him a pair of nasty karate chops to the throat. He tries to tear Lawrence's hand in two by pulling two handfuls of fingers in opposite directions. Lang choreographs the action for visual clarity, rubbing our noses in the traumatic details; this may be the first really graphic killing scene in an American movie. Any kid who's taken a Tae Kwon Do class will see that the action is actually far too slow to be real; 1946 entertainment didn't move at a video game pace, that's for sure. But the scene makes unforgettable use of violent detail.

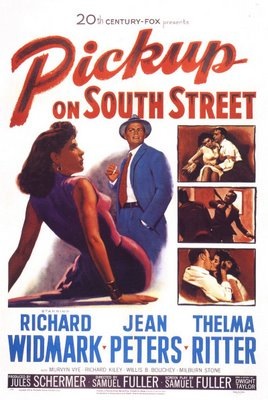

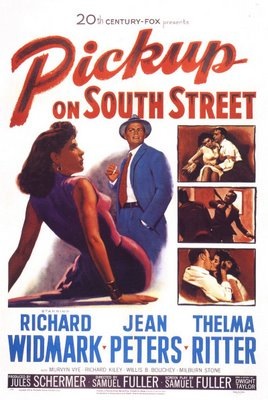

2. In Sam Fuller's Pickup on South Street (1953), Communist spy Richard Kiley goes berserk on his girlfriend Jean Peters. She's just out of the tub and is wearing little more than a bathrobe when Kiley literally "cleans house" with her, slapping and shoving the young woman into walls and furniture. It's all done in one take, with Fuller's camera jerking back sharply to catch the action. Because it's one unbroken shot, we can see that the stars are really going at it -- no cheats, no doubles. The flimsy bathrobe tells us that it's really Howard Hughes' girlfriend, and not a stunt player. 2 Peters exaggerates her distress, jerking her head around to accentuate the violence, but her impacts knock over real tables and lamps. Although not a conventional fistfight, the effect of this one-shot scene stands in contrast to the heavy cutting in so many of today's fights. Combine today's editorial shortcuts with wire removal, padding removal, and CGI face replacement, and nothing is real. In Pickup we can tell that Ms. Peters took some risks, and probably ended up with a few bruises.

3. From Russia with Love (1963) is directed by Terence Young with an assist from the English "stunt arranger" Peter Perkins. Here at last is something to compare with Batman, a grudge match between bigger-than-life adversaries, the suave but brutal 007 (Sean Connery) and the beefy bruiser Red Grant (Robert Shaw). Grant has Bond dead to rights in a tiny sleeping compartment on the Orient Express, but delays shooting him to gloat over his victory. Bond is waiting to be killed, execution-style, when an opportunity arises to turn the tables on his captor.

The ensuing fight is a two-minute ordeal of bashing, smashing and bone-crunching blows. The extremely confined space forces Young to stay in close at all times; there's barely enough space to throw a punch. Editor Peter Hunt demonstrates his mastery of subliminal "up-cutting", removing just a frame or two to keep the action from seeming to pause. The camera swings violently to match Bond as he uses Grant as a battering ram, slamming him into the cabinetry left and right. The fighting is so up close that the sequence must be studied to find shots where stuntmen Perkins and Jack Cooper replace the star actors. Connery hit a few bad guys in Dr. No but this is the first Bond scene that earned spontaneous audience applause. The carefully designed and filmed sequence stresses physical action over editorial pyrotechnics.

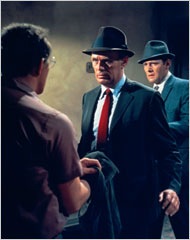

4. Don Siegel's Madigan (1968) doesn't even have a fist fight, but it's the best example I can think of to express the way a great filmmaker withholds action for maximum impact. Detective Daniel Madigan suffers an existential cop crisis. Psycho crook Barney Benesch (Steve Ihnat) steals his gun and uses it to kill another policeman.

For a supposed action film, Madigan keeps the action on a small scale -- foot chases, a brutal shooting -- to build up Madigan's frustration. Siegel lets the drama rise to a boiling point. When Benesch is finally cornered Madigan is desperate to make the arrest personally. He's in too great of a hurry to even put on a bulletproof vest. The whole film rides on the one action moment. Another cop blasts the door open with a shotgun and Madigan leaps into Benesch's kitchen, blazing away with a gun in each hand. At the other end of the kitchen, Benesch is doing the same thing. For a couple of seconds, Siegel's editing style jumps ahead thirty years. We flash-cut back and forth as the shooters empty their guns at one another point-blank. It's really only four or five quick cuts, but in 1968 the moment seemed to last forever. The gunfight has the impact of a blowtorch -- it's as if we are being hit by all those shots.

Madigan could build slowly toward its blazing finale, but new action films require a major climax in every reel. The need to provide continual action means that they can't afford to establish moods or build characters unless action is involved. Every flashback of significance must be an action scene. Narratives become repetitious. We sometimes find ourselves bored by action overkill, waiting for the supposedly "exciting" stuff to be over so the story can progress, if there is a story.

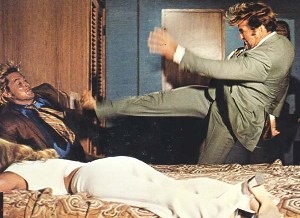

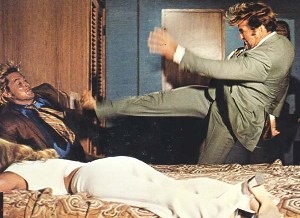

5. The first post-production code movie fight I remember that really pulled out all the stops was 1970's Darker Than Amber, directed by Robert Clouse, with Roger Creed serving as stunt coordinator. We'd seen big budget pictures that showcased exploitative violence -- Dark of the Sun, Beach Red -- but Darker Than Amber had the audience cheering like they were at a wrestling match. I can imagine the seven year-old Quentin Tarantino catching it on a double bill and being changed forever.

Tough guy private eye Travis McGee (Rod Taylor) deals with mob murders in Miami and helps a moll in distress (Suzy Kendall) find out who killed her twin sister. The film ends with a bloody dockside donnybrook with a thug named Terry, played by exploitation icon William Smith. The McGee-Terry fight sets a standard in gross-out overkill. They begin trading staggering blows in a ship's compartment. Terry hurls McGee through closet doors and into a doorjamb; Travis is a bloody mess when Terry tries to escape down the ship's gangplank. Terry takes on half the ship's crew before the cops arrive, and by that time he's so banged up and blood-soaked that he looks like he's been scalped. When McGee catches up, he's far too exhausted to fight fair, and instead swings a wooden 4x4 at Terry's legs, chopping him down like a tree. Darker Than Amber isn't a great picture overall, but that fight is better than anything in the ensuing decade of Grindhouse exploitation.

To get a desired rating, a new movie can't have that kind of realistic bloodletting. A dozen crushing blows might be exchanged but unless the film is an intentional gorefest like, say Sin City, we rarely see any serious damage inflicted. In Darker Than Amber, it's obvious that Rod Taylor and William Smith are really into the spirit of mayhem.

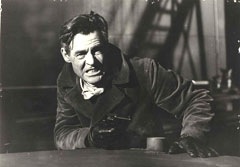

6. This last example shows a couple of concepts lost in the shuffle of kickboxing Incan warriors and superheroes who use eastern spiritualism to enhance their wire-rigged athletics. A brief but important scene in Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) demonstrates that (A) Less Is More, and (B) Action Can Express Character. Robert Ryan's aging, racist criminal Earle Slater is a very bitter man. He has a barroom confrontation with a punk soldier played by Wayne Rogers, later of TV's M*A*S*H.

Earle is drinking quietly while the soldier shows off his army training to his girlfriend (a young Zohra Lampert). Earle finally makes a surly comment and the soldier calls him out to fight. Rogers even offers to go easy on Earle, that it's a friendly contest. "Leave him alone, he's an old guy", Lampert says, and that's enough to goad Earle to face off with a kid half his age. The fight is over before it begins. For Earle it's no game. He blocks Rogers' best punch and delivers a single blow to the stomach, hard. Rogers goes down gasping for air. Earle has defended his honor and proved that experience still counts, but his triumph is over in a flash -- both the bartender and the girlfriend consider him the villain for trying to kill such a nice boy. Earle grabs his coat and hat, and exits more embittered than ever. We now know that Earle Slater is a very dangerous man, incapable of controlling his inner rage.

Yes, there's hardly any point in directly comparing Odds Against Tomorrow with The Dark Knight, as they have entirely different aims as movies. The new Batman series does scale its action scenes to the requirements of its comic book character. But too many of today's films measure out generic action by the yard, and substitute technical flash for actual action performances. CGI and other special effects turn thrillers into animated cartoons, with Casino Royale's 007 leaping from construction cranes to skyscrapers almost as if James Bond were in direct competition with Spiderman. With hundreds of millions of dollars at stake, perhaps it has to be that way. 3

July 20, 2008

Republished in concert with film.com .

Footnotes:

1. Speaking of still poses, Jean-Luc Godard indulged a personal joke in his spy epic Alphaville. Every time a "dynamic" fight scene was required, he simply had his actors take up still poses indicating "key frames" in a fight scene he never filmed. "I'm too intellectual to indulge in such nonsense", Godard seems to be saying, "So here's a generic action place-holder. Fill in your own damn action scene."

Return

2. Perhaps the ultimate expression of this vulnerability is the fight in the Turkish bath in David Cronenberg's Eastern Promises. Viggo Mortensen is stark naked throughout the entire scene, making it impossible to use a substitute body, or to even pad his elbows for a fall. And unless they found a way to fake the hard tile walls and floors, every fall and impact looks especially painful. We can depend on Cronenberg to not follow current trends.

Return

3. A note from reader William Wind,7.25.08:

I just read your excellent article Whatever Happened to Great Fight Scenes? I believe that in today's films, editing is used more to obscure than to enhance --- and I believe this applies to all types of films, not just action films and fight scenes. As you point out, the excellent choreography in Chicago is obscured by the rapid cutting to body parts instead of showing full figures in full motion (I liked the movie anyway, but it could have been so much better). The same problem exists in the recently released Mamma Mia! in which the filmmakers decided to "juice up" the dance scenes with fast editing, instead of relying on the energy of the performers to carry the scenes (as was done in Hairspray last summer)..

This MTV mentality has even carried over into straight dramas and comedies without action scenes. Whenever the emotions rise in a drama, the director switches to handheld shakycam and fast editing to hype the intensity of the scene --- but it has the opposite effect, because we can no longer get a clear image of the actors' faces. The same thing happens in comedies --- when the level of comedy rises, so does the editing, robbing us of the actors' performances. Maybe you can do another article, "Whatever Happened to the Slow Burn?"

There is no doubt that computer-based non-linear editing systems have made the editor's job much easier (they certainly have for me), but NLE has also put a terrible temptation in the editor's path: just because hyper-editing is now possible, it doesn't mean that you should use it all the time.

One of my all-time favorite fight scenes is the sequence between Gregory Peck and Charlton Heston in The Big Country (I'm sure you are very familiar with it). I wonder what today's editors would think of the languid pace (and extreme wide-angle images) in that sequence? And yet it works perfectly, ending with Peck's classic question, "What did we prove?" That's William Wyler for you. -- Bill Wind, Lakewood Colorado

Return

DVD Savant Text © Copyright 2008 Glenn Erickson

Go BACK to the Savant Main Page.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Return to Top of Page

|