| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

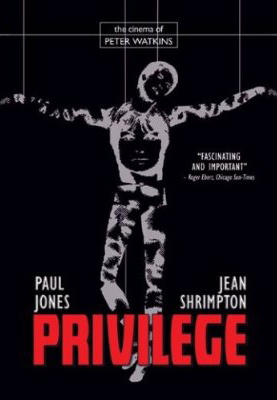

Privilege |

|

Privilege Project X / New Yorker Video 1967 / Color / 1:85 anamorphic widescreen / 103 min. / Street Date July 29, 2008 / 29.95 Starring Paul Jones, Jean Shrimpton, Mark London, William Job, Max Bacon, Malcolm Rogers Cinematography Peer Suschitsky Art Direction Bill Brodie Film Editor John Trumper Original Music Mike Leander Written by Johnny Speight, Norman Bogner Produced by John Heyman Directed by Peter Watkins |

Privilege is a Universal release from 1967 with a very troubled history. Fresh off a major controversy with his 1965 BBC show The War Game, director Peter Watkins' first 35mm theatrical feature is a political swipe at a perceived collusion of big government and the entertainment industry, starring ex- Manfred Mann singer Paul Jones as a pop star used as a tool to manipulate the masses. The still-conservative English film establishment did not give the show a general release; after short runs in the U.K. and America it quickly disappeared from view.

For the past four years Oliver Groom of Project X have been carefully producing DVDs of the unique films of Peter Watkins. Universal controls the title and almost never allowed it out for showings. Made widely available at last, Privilege is an intellectually challenging but somewhat frustrating attempt by Watkins to move his pseudo-docu BBC style to the big screen.

Most television and short film directors use the jump to mainstream feature filmmaking to embrace standard commercial forms, even noted English talents like John Schlesinger and Richard Lester. Privilege must have sounded like a perfect moneymaker: a rebel director taking on the world of pop music in a film headlined by a rock star and a top model. Peter Watkins instead came out with a very un-commercial show that fits into no easy category.

Privilege only has one or two original songs and cannot be considered a pop concert film. Its underdeveloped narrative has no action; a droning Culloden- like narrator explains most of what happens, leaving us with slowly paced dialogue scenes. In many of these Steven Shorter's unpleasant associates harangue the camera. Paul Jones mopes and grimaces as if suffering from indigestion. The beautiful Jean Shrimpton can't be as monotonous in real life as she is here; Watkins must have directed her to behave so stiffly.

In the extras Watkins himself says that Privilege is a look at the phenomenon of the pop star. Watkins was inspired by a short subject on Paul Anka (included on the disc) but shows superstar Steven Shorter already worshipped on a level far surpassing even the Beatles. He's practically considered The Messiah.

Watkins' real purpose is social commentary, communicated mostly through ironic narration. Finding that they no longer have any real differences, the House of Commons and the House of Lords form a coalition government and seek a benevolent permanent rule. They mount a giant Church / State torch-lit gathering modeled none-too-subtly on a Nazi-style rally, complete with marching banners. The film shows officials of the Church of England auditioning a rock version of the hymn "Jerusalem" and conspiring to use Steven to re-popularize organized religion. It works: after his first rally, 47,000 new believers give themselves to Jesus. The power brokers give Steven the "privilege" to do their bidding. Should he becomes a liability, their media machine can break him overnight. 1

Unfortunately, Watkins' film has many problems. Physically it looks under-budgeted, with cheap costumes sporting Steven Shorter (SS) emblems. Banners display his symbol, an arrow graphic that looks like a cross, but we must accept as a given Shorter's incredible popularity and influence. Steven begs for help but remains remote and unlikable. His handlers are all self-serving phonies and even Vanessa looks bored. All the improvisations and talking heads lack forward momentum.

Watkins seems allergic to the idea of conventional storytelling. Only the docu-flavored stage performance and the rally make an impression. Everything important in the film is presented as exposition instead of experience. Like Harry Lime in The Third Man, executive William Job lectures Steven on how he must use his influence to dominate the "little people" in the street below. Watkins is so intent on communicating ideas directly to his audience that he plays the bulk of he scene on the back of Steven's head, refusing to show his reaction.

The film is really political science fiction not unlike Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo's It Happened Here. Watkins and his writers' political ideas are very good; they fit present-day America to a tee. Voters complain that they lack meaningful candidates while the political parties seem to concern themselves entirely with media images to mold public opinion and get votes. The general suspicion is that a power elite controls all and diverts the public with cheap entertainment. Complacent conformism may not be promoted as the ultimate virtue, but activism is discouraged.

Critics of Privilege suggest that the movie may have been refused wide release in England because of its view of the Church as just another corporation angling for power over the public. When someone suggests that a partnership with Steven Shorter Inc. is inadvisable, he's silenced with the statement that sermons are playing to empty churches. The implication is that organized churches are in the entertainment business; the govenment wants young people off praying instead of getting involved in politics. It's not uncommon for that kind of challenging idea to attract violent opposition.

Ironically, an American-International rip-off called Wild in the Streets took the same story in a different direction, sticking to safe satirical targets like stuffy congressmen and twisted mother worship. The copycat film is cheap and sloppy, but it made money and generated a hit song, The Shape of Things to Come. We also wonder if Privilege inspired The Who's rock opera Tommy. Steven Shorter isn't blind, deaf or dumb but the parallels are pretty close, right down to the superstar's mass rejection and his pleas for human understanding.

Project X and New Yorker's bold release of Peter Watkins' Privilege adds another controversial title to the collection, alongside Punishment Park and The Gladiators. The extras focus on the film's theme of superstardom and include a fine transfer of the B&W National Film Board of Canada short subject Lonely Boy (1962, 26 minutes), which Watkins says was his main inspiration. The director's candid and thorough self-interview stresses his belief that the MAVM (Mass Audiovisual Medium) warps our perceptions and controls our thoughts every bit as much as the propaganda of a totalitarian state.

A chapter on Privilege from a book by Joseph Gomez appears, along with a current postscript in which the author tempers some of his views. An essay by Barry Keith Grant is included, along with generous galleries of stills and posters.

Privilege is analyzed in almost every study of the Science Fiction film; I'm grateful to have caught up with it at last.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Privilege rates:

Movie: Good

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: 26 minute short film Lonely Boy, trailer, galleries of stills and posters, insert booklet with essays by Joseph Gomez and Barry Keith Grant, plus a new self-interview by Peter Watkins.

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: July 27, 2008

Footnote:

1. I keep saying that Watkins' theme of youth celebrity is not handled well, but he gets this aspect exactly right. John Lennon was tolerated as long as he remained apolitical. When he stopped hiding his personal beliefs and used his celebrity to politely speak out against war and greed, "the system" did indeed come down on him from all directions. He was lambasted as a drug user and marginalized as a kook. A vicious misquote demonized him for saying he was "more popular than Jesus". We're all encouraged to speak our own opinions, as long as nobody listens -- Lennon was dangerously popular.

Return

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |