| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

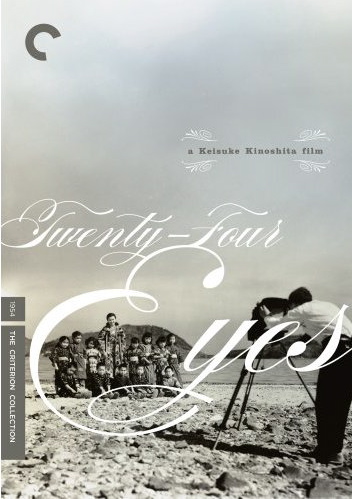

Twenty-Four Eyes |

|

Twenty-Four Eyes Criterion 442 1954 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 156 min. / Nijushi no hitomi / Street Date August 19, 2008 / 29.95 Starring Hideko Takamine, Chishu Ryu Cinematography Hiroyuki Kusuda Art Direction Kimihiko Nakamura Original Music Chuji Kinoshita Written by Keisuke Kinoshita from the novel by Sakae Tsuboi Produced by Ryotaro Kuwata Directed by Keisuke Kinoshita |

Japanese classics encompass more than Samurai films, Kurosawa epics and family dramas from Yasujiro Ozu. One of the most popular home-grown Japanese films ever is 1954's Twenty-Four Eyes, a moving story about twenty years in the life of a grade school teacher on a rural fishing island. Instantly recognizable as an Eastern variation on the "women's weepie" subgenre typified by American films like Stella Dallas, director Keisuke Kinoshita's beautifully composed film focuses on the emotional trials of its leading character as she suffers through both an economic depression and a war.

Surprisingly enough, we learn from the disc extras that the pacifist-themed Twenty-Four Eyes had to wait for the end of the American Occupation to go into production.

The episodic, openly sentimental Twenty-Four Eyes wins us in the very first scene when Hisako meets the adorable children that will figure in her life for the next two decades. She does everything right but history thwarts her mission to better their lives. The poverty and politics of the Depression years take a terrible toll, just as happened here in the United States.

The movie focuses almost exclusively on Hisako's personal experience and that of her innocent students. Her beloved husband makes only brief appearances as a bridegroom, a boat captain, and when waiting to be called up to serve. We judge Hisako's character almost exclusively by her exterior graces. Clearly the very model of an ideal Japanese woman, she's bright and charming at work, and responds to every crisis with grace and dignity. Painfully injured in a fall, Hisako politely asks the children to summon aid (children do a lot of running in this movie). When her entire class walks ten miles to see her and arrives tired and hungry, she feeds them despite the fact that she's on crutches.

An idyllic early scene shows Hisako and her brood dancing and singing in a grove of flowering trees. With the onset of the depression, parents withdraw their children to work at home. Heartbroken, Hisako must put up a front of neutrality when her students seem desperate to stay in school. She watches helplessly as the promise of the future is dismantled student by student. Hisako sheds plenty of tears both privately and with others; director Kinoshita's emotional clarity pretty much guarantees that viewers will mist up as well. Interestingly, the director uses sentimental Western tunes for key transitions: Auld Lang Syne; the hymn What a Friend We Have in Jesus.

Keisuke Kinoshita reportedly ran into trouble during the war by filming scenes counter to guidelines laid down by Japan's military government. Twenty-Four Eyes is a full-on criticism of the war years. Literally every service-age male goes off to war accompanied by songs urging a happy death for the honor of the Emperor, and few return. Hisako witnesses the destruction of a generation and her personal happiness to events out of her control. The scenes after the war are bittersweet in the extreme. Hisako is invited to a small celebration by a few of her old students, almost all of them women.

Twenty-Four Eyes' closest contemporary American counterpart is the 1955 soaper Good Morning, Miss Dove, a rather forced weepie with Jennifer Jones remembering a lifetime of teaching from her sickbed. Kinoshita's movie never becomes maudlin, despite the fact that almost every scene in its second half is visited by some sort of tragedy. Despite the sadness, the general mood is one of uplift. The director invests his many exteriors with the feeling that all hardship will eventually pass.

Viewers unaware of the social realities of earlier times may become irritated that Hisako doesn't assert herself more; just riding a bicycle makes her suspicious in the eyes of many. She quietly accepts the principal's hysterical burning of her "Red" pamphlet during the anti-Communist scare. We're told that Japanese educators were terrorized by mass firings and bullied into silence on political subjects. This content from the original Sakae Tsuboi novel is probably what kept Twenty-Four Eyes from being produced earlier, when Americans oversaw Japanese film production. In the early 1950s, the exact same witch hunt fever was at large in the United States.

The youthful-looking Hideko Takamine ages twenty years as the adorable teacher Hisako; we'd never believe that Twenty-Four Eyes was her 130th film appearance. Revered actor Chishu Ryu plays a decent but unimaginative teaching colleague. This sentimental saga won many Japanese awards. In America it won a Best Foreign Film Golden Globe, even when cut by 38 minutes. It was remade in color in 1987.

Criterion's DVD of Shochiku's Twenty-Four Eyes is a good B&W transfer that only occasionally shows signs of fluctuating density. Otherwise it's clean and sharp, with a solid soundtrack. Director Keisuke Kinoshita passed away in 1998, so critic Tadao Sato hosts the fascinating featurette on the making of the film. In many cases, we're told, the actors playing students were cast with look-alike brother - sister pairs, to maintain continuity as the children aged on screen. The teasers and trailers provided are formatted in Wide Screen and appear to be from a later reissue. Disc producer Curtis Tsui provides an insert booklet with an essay by Audie Bock and a 1955 text interview with director Kinoshita.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Twenty-Four Eyes rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Featurette, trailers, essay, text interview

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: August 26, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |