| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |

| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray International DVDs Theatrical Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk TV DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant HD Talk Horror DVDs Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

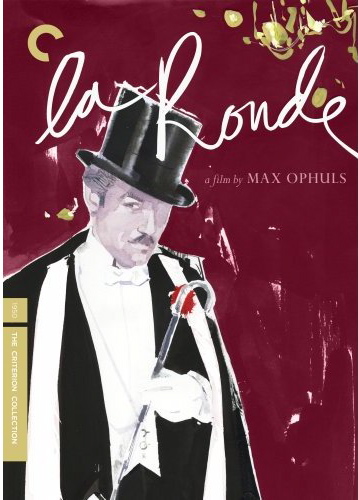

La Ronde |

|

La Ronde Criterion 443 1950 / B&W / 1:33 flat full frame / 93 min. / Street Date , 2008 / Starring Anton Walbrook, Simone Simon, Simone Signoret, Daniel Gélin, Serge Reggiani, Danielle Darrieux, Fernand Gravey, Odette Joyeux, Jean-Louis Barrault, Isa Miranda, Gérard Philipe Cinematography Christian Matras Art Direction Jean d'Eaubonne Film Editor Léonide Azar Original Music Oscar Straus Written by Jacques Natanson & Max Ophuls based on a play by Arthur Schnitzler Produced by Sacha Gordine Directed by Max Ophuls |

After seeing Max Ophuls' La Ronde we can easily understand why foreign films made such a big impact on postwar film fans in New York and other culture centers. Americans were accustomed to commercial fare dumbed down to appeal to twelve year-olds, and combed by censors to eliminate any trace of controversy. La Ronde concerns the interlocking liasons of a dozen lovers that form a chain of human desire -- lust, vanity, possession, ambition, gamesmanship and commerce. Adapted from a notorious play by Arthur Schnitzler, the show is a sex farce by strict definition only. It's a slightly fantastic and only partly satirical examination of the way the sex drive seems to motivate everything in the well-to-do European society depicted. Desire is what makes the players so foolish, and so human.

Directed with sublime delicacy and authority, La Ronde was the success that allowed Max Ophuls to commence a short but productive third career after a decade of exile in Hollywood. He brought back from America a desire for technical perfection that blends well with his continental tastes. What begins as an exercise in narrative gimmickry soon becomes something rare and profound.

Roughly speaking, La Ronde is a naughty farce with the smirks and off-color jokes deleted. In its place is a respect for characters and a gentle understanding of human weakness. Anton Walbrook (The Red Shoes, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp) is an omniscient "stage manager" master of ceremonies who observes the carousel of love affairs, and frequently steps in to play the roles of waiters and servants. He addresses the audience directly and will flash winks of recognition in our direction, even in the middle of dramatic scenes.

A prostitute picks up a soldier, who later romances a housemaid in the park outside a dance hall. The maid takes a new job far away, and allows herself to be seduced by her employers' young son. The circle of erotic connections, all portrayed with taste and discretion, continues. A bored housewives cheats on her husband and the husband reaffirms his masculinity by taking a mistress. A vain poet conquers a coquette but himself cowers before the advances of a worldly actress. All the players are looking for excitement or romance, and not necessarily love. They're motivated by the secret desire for experience that will make them feel alive. Taken as individuals the lovers are pompous or naïve; the coachmen and waiters have a better picture of what's really going on than they do. Ophul's circular narrative puts them all on a figurative carousel, eternally chasing their desire in circles.

Ophuls attracted the cream of the French acting community, mixing established names like Danielle Darrieux and Simone Simon (who also had a brief Hollywood career) with old timers like Fernand Gravey and relative beginners like Daniel Gélin and Gérard Phillipe. Simone Signoret plays a believable prostitute, not the de-sexed, sentimentalized "thing" of American films of the time. Famed Italian actress Isa Miranda is the grand actress who knows full well how to steer a nervous poet to her bed when she wants him there.

Some famous directors are praised for their presumed skill in shaping performances. Others are analyzed as masters of technique, to such a degree that visual flamboyance becomes an end unto its own. With Max Ophuls the two concerns are inseparable. His camera is always on the move, but always closely in tune with the actions and emotions of the characters. Ophuls' sets are often designed to allow the camera to follow actors up and down stairs and through elaborate spaces; yet we never get the sense of a giant camera in the room, crowding its way around.

Ophuls uses sentimental music but reserves his sentiments for lovers in general, and not the amusing case studies on view. The people may be honest or deceitful but all deceive themselves in the search for some ideal. The raconteur played by Walbrook is a good substitute for the director, guiding us from vignette to vignette and sometimes even setting the stage. He takes Simone Simon's housemaid by the arm and transports her not only to the next setting, but across two years of time. When she arrives, she has a new job and a new costume.

Someone like Ernst Lubitsch would broaden every performance and introduce sly jokes; Billy Wilder would introduce more cynicism with cutting comedy dialogues. Ophuls maintains a tone of bemusement but goes for jokes only a few times. Daniel Gélin's eager student gets a married woman into bed, only to find that he can't perform. Ophuls cuts to Walbrook witnessing his merry-go-round break down, and sets to fixing it. A bit later, Gélin and his conquest get the mechanism back in action again.

Later on, the camera swoops directly into a fancy-dress sex scene, but again we cut away at a choice moment -- to Walbrook, holding a strip of film up to a light. He takes a pair of scissors and censors the offending footage, before returning us to the bedroom scene. Many films break the third wall to inject jokes from outside the play-world in progress; La Ronde does it with an elegance unmatched anywhere. Ophuls resolves his unending circle of conquests with the greater insight that much of life is dictated by our sexual desires. The sad thing about La Ronde is that all these lovers searching for some fleeting romantic ideal ultimately remain strangers to one another ... the recurring image is of solitary people walking alone in the night.

Criterion's La Ronde is yet another stunning DVD presentation with clean video and and a clear audio track for Oscar Straus' beautiful and touching music score. The audio commentary by Susan White takes the full measure of Ophuls' career, while an Interview with the director's son Marcel provides another perspective. Daniel Gélin shares his memories of working with Ophuls, and film scholar Alan Williams discusses the film as a whole. Terrence Rafferty provides a very helpful essay on La Ronde for the insert booklet.

Of special interest is an exchange of letters between Sir Laurence Olivier and Heinrich Schnitzler about Arthur Schnitzler's original source play. The play was prohibited from performance in most countries by the playright himself, because interpreters invariably turned it into a sex farce and brought down censors and scandal. The wisdom of that choice choice is perhaps proven by Roger Vadim's version done fourteen years later. With Jane Fonda prancing at the center of a series of lame sex scenes, it drains most everything of value from the story.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

La Ronde rates:

Movie: Excellent

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: Audio Commentary from Susan White, Interview with Marcel Ophuls, Interviews with actor Daniel Gélin and film scholar Alan Williams, correspondence between Sir Laurence Olivier and Heinrich Schnitzler about the source play, insert essay by Terrence Rafferty

Packaging: Card and plastic folding disc holder in card sleeve

Reviewed: September 10, 2008

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are more likely to be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum

Copyright © MH Sub I, LLC dba Internet Brands. | Privacy Policy

Subscribe to DVDTalk's Newsletters

|

| Release List | Reviews | Price Search | Shop | SUBSCRIBE | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray/ HD DVD | Advertise |