|

|

|

|

The amazingly creative Fritz Lang almost singlehandedly pioneered the sophisticated leading edge of the fantasy epic, the gangster film, the spy thriller, and the science fiction film -- starting before the sound era. Continuing his career in the United States, Lang's spy chases and crime exposés examined the nature of the law and justice, and the moral limitations of society. His socially conscious protest pictures Fury and You Only Live Once are also cinematic masterpieces. Testimony pretty well acknowledges that Fritz Lang was one of the most dictatorial and disliked directors ever to work in American studios. He didn't play studio politics well and some actors refused to work with him a second time. On the other hand, star Vincent Price described Lang as, "such a wonderful man. Charming, cultured, a really intelligent man. An artist." Never finding a steady career roost, the director moved from studios to independent producers, making just enough hits to keep going. This pattern pretty much played out in the middle 1950s as the industry retrenched for hard times. Lang returned to MGM to make Moonfleet and then filmed what would become his last two American pictures back to back for the independent producer Bert Friedlob. They were made very economically, with name stars a few years past their prime. But Lang fashioned each show to address growing issues in American crime: Is capital punishment a good policy? And how does society deal with a serial killer?

The complex While the City Sleeps coordinates numerous characters in a classy screenplay by veteran scribe Casey Robinson. The very modern construction contrasts the psychoses of the twisted young "lipstick killer" Robert Manners (John Barrymore, Jr., with the office politics at Kyne Media Enterprises, all of which also center on money, power and sex. When the rich founder dies, his arrogant son Walter Kyne (Vincent Price) takes over the empire, which includes newspapers, a news wire service and a TV station. These divisions are run by aggressive males: Pulitzer prizewinning reporter Ed Mobley (Dana Andrews), sneaky news wire chief Mark Loving (George Sanders), crusty newspaper editor Jon Day Griffith (Thomas Mitchell) and the unscrupulous photo editor Harry Kritzer (James Craig). Kyne announces a competition for a new executive position -- the man who catches The Lipstick Killer will get the job. "Women's" reporter Mildred Donner (Ida Lupino) watches with interest as Loving and Griffith jockey for the best shortcut to the prize. Harry Kritzer is having an affair with Kyne's wife Dorothy (Rhonda Fleming) and seems to think that her influence can secure the job for him. The principled Edward Mobley seems the best candidate despite being a heavy drinker. He's keen on nabbing the Lipstick Killer, but not for the promotion. He and detective Burt Kaufman (Howard Duff) plan to set their trap by using out Mobley's own fianceé Nancy Liggett (Sally Forrest) as bait. The main irony in While the City Sleeps is that the legitimate drive for money and advancement is almost as recklessly anti-social as the depredations of the insane killer. Lang made the first and uniquely sympathetic examination of a child murderer back in 1931 with his first sound film "M". Twenty-five years later he's still fascinated by the way society reacts to catch a deadly menace. Barrymore Jr.'s Robert Manners is a mama's boy with a fierce desire to let out his aggressions on helpless women. Over at the Kyne building, the business of disseminating the news comes in a distant second to the political infighting. The executives couldn't be happier than when one of their underhanded tricks makes a competitor look bad. Only Ed Mobley seriously attacks the problem of identifying the Lipstick Killer, and decides (like Howard Beale 20 years later in Network) that his broadcast pulpit can be used to goad and taunt the killer into showing himself. Lang amuses himself by directly comparing Mobley with the Lipstick Killer. Both use the same trick to enter a girl's room unawares, and Mobley's uncouth, alcohol-fueled advances to Nancy ("I want to explore in uncharted territory...") can seem as obsessive as the twisted mother fixation that prompts Manners to kill beautiful women.

The various plots and strategies see the Kyne executives forming old-boy alliances in the downstairs bar. Mobley's plan works in that it prompts Manners to seek a personal vengeance against the reporter who calls him a crybaby over the television. Mobley himself is barely fit to carry out his own plan, however. He drinks too much and alienates Nancy over the attentions of Mildred Donner, who would love to poach Ed for herself. When Nancy gets angry she forgets about the threat to her life -- just as the killer has learned where she lives. The title While the City Sleeps implies that the public doesn't know that the real workings of the city are organized chaos. In contrast to the reassurance offered by other '50s stories of high-stakes games in American business, an extended epilogue shows us an even more absurd reshuffling of the executive pecking order at Kyne Enterprises. The film's stock relationships and constant banter can seem old-fashioned, like something from a 1930s cops 'n' reporters drama, but the underpinnings are much more modern. The movie is very aware that society is becoming more stressful, and perhaps nearing a breaking point. The moral stakes are bigger than ever, and the city's 'responsible' businessmen don't seem to be up to the task. While the City Sleeps is one of the better pictures from RKO's twilight year, and an excellent late-period film noir. Casey Robinson's screenplay gives the ensemble cast of seasoned pro actors plenty to work with, and something interesting is always happening. Earning mostly positive reviews, it's considered one of Fritz Lang's better American movies. Writer Morrow or Fritz Lang or both apparently subscribed to Doctor Wertham's theory that violent comic books have a direct relationship to crime, as that issue is harped on more than once in the screenplay. Producer Friedlob played up the angle with a publicity announcement that invited a U.S. Senate subcommittee investigating juvenile delinquency to use the movie as "a weapon in the growing battle against the corrupting force of comic books on young minds."

Released later in the same year, the deceptively small-scale Beyond a Reasonable Doubt pays off with a number of genuinely surprising narrative and thematic twists. Fritz Lang and his scenarist Douglas Morrow seem delighted with the idea of a principled man purposely misleading the justice system to prove a point. The movie is talky, as plenty of redundant dialogue is included to keep the story's all-important premise clear. The result isn't quite as shocking as it once was -- modern audiences expect every story assumption to be overturned -- but film scholars are still debating the film's ending. Wealthy publisher Austin Spencer (Sidney Blackmer of Rosemary's Baby) is so determined to make a public statement about the evils of capital punishment that he entreats his future son-in-law, successful writer Tom Garrett (Dana Andrews) to cooperate with him on a risky scheme. Austin and Tom choose an unsolved murder of a showgirl from the tabloids and then rig evidence to "frame" Tom for the crime. The idea is that, after Tom is arrested and convicted, Austin will come forward with proof of their trickery, forcing the courts to pardon Tom and admit that the system can be thwarted to convict an innocent man. Thus Austin will get publicity for his national anti- capital punishment campaign. The process necessitates Tom hanging around the strip club where the victim worked and dating one of her girlfriends, stripper Dolly Moore (Barbara Nichols). But the scheme must be kept a secret from Tom's fianceé Susan Spencer (Joan Fontaine), who is so hurt by Tom's actions that she breaks off the engagement. Susan stands by her man when the trial commences. Everything works as planned until the jury goes into deliberations and Austin prepares to take the evidence proving Tom's innocence to the district attorney. Then Tom suddenly finds himself alone, with no proof that he isn't guilty as charged, and no Austin to back up his wild tale of a pact to defraud the courts for a good cause. Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is almost all talk and little action, yet its intriguing concept carries the day. The challenge for the actors is to make the unlikely events seem believable. We accept the fact that a 1956 audience needs each act of rigged evidence to be spelled out for them; the fun is trying to predict what the story twists will be. Chances are that newcomers to the movie will guess at least one or two of them. With that in mind, I'll skip further discussion of the film's major plot points. If you haven't yet had this movie spoiled, try to avoid reading too much about it before your first viewing. Even if you conclude that the film's mystery is now easy to guess, a second viewing will reveal patterns of behavior and unexplained actions that show how carefully Morrow and Lang have worked out their thesis. The disturbing element in Beyond a Reasonable Doubt emerges from the details -- if what we "know" as fact and fiction emerges from such tiny clues that can either be forgotten or exaggerated, then the moral implications of everything that gets reported in the newspapers isn't as simple as we think it is. Are right and wrong, & guilt and innocence determined by arbitrary factors? Lang questions whether or not individual guilt is really an abstract concept. Finally, the film asks us to question the nature of loyalty in a relationship. At the finish, does Susan Spencer act out of a higher morality, or is she getting personal revenge for petty reasons? Who has betrayed whom?

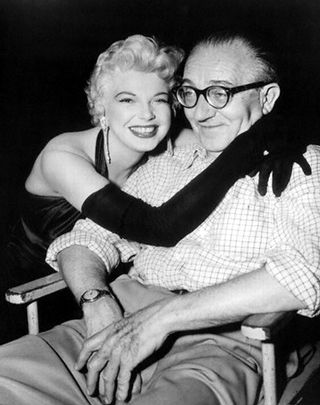

Unlike its sister film Beyond a Reasonable Doubt got a mixed critical reception. More than one upscale critic were quick to find detail flaws and legal inconsistencies, as if they were incensed that they might have been fooled by some of Doubt's faster narrative turns. Audiences probably would have preferred more in the way of action, as a bit of dancing on the burlesque stage is the only break from the (admittedly good) dialogue scenes. The movie was appreciated much more a few years later, when auteur-minded critics reexamining Lang's career fell over themselves to praise the director's questioning of the loose ends of the justice system. Image directly above: director Fritz Lang discusses serious issues of morals and ethics with star Barbara Nichols.

The Warner Archive Collection's DVD-Rs of While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt have been transferred in their appropriate Superscope aspect ratio -- 2:1 (for some reason, projectionists have always written this backwards). An argument has circulated since the days of Laserdiscs over whether Fritz Lang filmed these movies with normal 1:85 widescreen in mind, or whether the cameramen designed them to be cropped and squeezed for anamorphic projection. Along with clues from reference books, seeing the WAC's properly formatted discs one after the other prompts me to offer what I think is the likely truth on the subject. Producer Friedlob had originally planned to distribute While the City Sleeps through United Artists, but the film shifted to RKO, which had nothing to do with its production. I believe that Sleeps was most likely filmed with 1:85 or perhaps even 1:66 projection in mind, and that RKO had it re-formatted for widescreen projection. RKO was at the time pushing the Tushinsky Bros.' Superscope process. Old open-matte TV prints showed significant dead picture area north and south, but the theatrical 'Superscope' image, properly matted 2:1 on the WAC disc, frequently looks compositionally awkward and crops chins very closely. Most telling is a close-up insert of a note read by the killer, in which Ed Mobley's name (important information) is almost completely cut off. This would certainly account for the sources that say that Fritz Lang was unhappy with the film's final release format. While the City Sleeps also looks a bit soft and grainy, indicating that it was re-formatted like original Superscope, not using the soundtrack area. The picture area remaining to be enlarged to 'Scope is scarcely bigger than two 16mm frames, side by side. Filmed soon afterward, Beyond a Reasonable Doubt was almost certainly planned for the Superscope format from the beginning. The original trailer included on the disc identifies the format as RK0-Scope. That's a proprietary name for Superscope 235, which exposes the entire 35mm frame left to right, including the soundtrack area, thereby obtaining a higher quality image. It's essentially the same system as Super 35, in heavy use today. The Warner Archive disc of Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is reasonably composed for widescreen, and exhibits no suspiciously cut-off chins. Although it wouldn't have been historically correct, a 1:85 scan or even a 1:78 scan of the original negative for both pictures wouldn't have been offensive. Of the two pictures Beyond a Reasonable Doubt is in better shape. While the City Sleeps has some surface mottling and other minor flaws here and there, as if taken from an old dupe neg with printing problems. But both movies hold up very well even on a large projection screen. The audio is quite dynamic, giving us a good concert of Herschel Burke Gilbert's exciting music scores.

A reminder again that these are separate discs from the Warner Archive Collection. The one extra is an intriguing original trailer on Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. Advice: Gary Teetzel. Research: The Films of Vincent Price by Lucky Chase Williams.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2010 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||