|

|

|

|

A surreal delight from the fertile mind of Jean Cocteau, this highly cinematic fairy tale Beauty and the Beast (La Belle et la bête) is an extension of the artist's more abstract art films, proving again that genre work is good for poetic visionaries. The magic and mystery of the original story takes on additional depth and beauty through a rich and tasteful production. Criterion's new Blu-ray gives the film the benefit of the painstaking digital restoration visible in classics like Children of Paradise. The new disc includes the original French opening first seen in America in 2003. Cocteau's script follows the contours of the original tale. Belle (Josette Day) is the sole respectful child of a merchant (Marcel André) whose ships have been lost at sea. Her brother Ludovic (Michel Auclair) is an idle gambler and her two sisters hate their father for damaging their social life with his financial problems. Returning from some unprofitable business, the merchant accepts the hospitality of a mysterious and magical castle, but inadvertently earns the wrath of its owner when he takes a rose from the garden. The lord of the castle is The Beast (Jean Marais), a furry, feral monster who smokes of brimstone when angered. The lonely Beast spares the merchant's life, but only on the condition that he send his daughter to take his place.

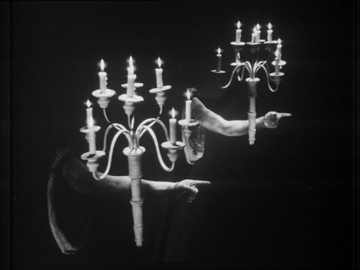

Beauty and the Beast is a visual feast, a sumptuous classic that, along with The Red Shoes, played a big role in popularizing foreign films for post-war American audiences. French poet and artist Jean Cocteau treats the fairy tale with intelligence and respect, and with simple special effects creates a world of magic and miracles that's never been matched. Josette Day presents Belle as a worldly and wise character with deep feelings and a strong commitment to virtue. She's independent and vulnerable at the same time. Jean Marais plays three roles, Beauty's rakish lout of a suitor, the Beast, and the transformed prince at the ending. We soon grow accustomed to the formidable cat-like Beast, and the sight of him changed into a smiling, dandyish Prince Charming is the film's only letdown. An oft-repeated quote claims that Greta Garbo, enchanted by the movie, shouted out loud at a screening, "Give me back my Beast!" Saying that the film succeeds simply because the original tale is taken seriously doesn't do the show justice. Beauty and the Beast is the best fairy tale on film because it approaches the story from an artist's perspective. Cocteau and his talented young cameraman Alekan consciously designed the picture to resemble illustrations by Gustav Doré and 17th century Dutch paintings. The soft lighting has little in common with the dominant Hollywood look of the day. Most of the action takes place in convincing locations and sets, where the characters behave like reasonable humans while reacting to incredible magic. Better still, the picture's aesthetic agenda doesn't result in a prissy atmosphere of preciousness. The world of The Beast is poetic, but also dynamic and dangerous. When the fantastic sets in, it is signalled by cinematic stylization instead of technical tricks -- the effects are simple and organic. We're pulled into the image instead of motivated to work on the practical puzzle of how they were done. Slow motion, reverse filming, simple substitution tricks are the majority of the effects used. Cocteau's surreal imagery does the rest, blending the animate and the inanimate. Disembodied arms hold torches, part curtains and pour liquids. In the woodcarvings around fireplaces are living cameos that follow humans with their eyes. Trees part magically to admit visitors to the garden. In this film, when doors and gates open by themselves, the simple magic works. 1 Some tricks, like the simple substitution of a pearl necklace for a mangy rope, work with the same basic misdirection a magician uses. The Beast is a full-fledged movie monster that transforms Jean Marais into a furry, fanged nobleman with feral eyes and a savage disposition. The triumph of design is integrated into the character instead of merely being a good mask, and puts much of the output of classic Hollywood horror to shame. 2 Curiously, The Beast at one point talks about the source of his power as if he is but a cog in some larger system of magic -- not unlike the magician Karswell and his Faustian pact in Jacques Tourneur's Curse of the Demon.

Cocteau interprets the conflicts of the original fairy tale with a clarity that makes them seem more like the problems of real people, even as everything that happens remains patently unreal. When first read, the original story of Beauty and the Beast can seem parable-thin: love conquers ugliness, virtue is its own reward, etc.. Cocteau makes the situations accessible and understandable. The financial plight of Belle's family is universally understood. The petty jealousy, greed and malice of her relatives is something most viewers have experienced. Good and Evil spring from human roots, not a fear-driven conception of the universe. The Beast does cruel things because he's lost his humanity and is half animal. Hate and fear warp his perceptions, inspiring a desire to shock and harm others for not acknowledging one's pain, or reciprocating one's feelings. The Beast mistrusts virtue. He seeks to unmask Belle's convictions as false, to find the ugliness in her. His initial act is to punish the merchant just for taking a rose, a penalty so disproportionate to the crime that it immediately indicates the Beast as the real criminal. 3 He lashes out because he is lonely and lovesick; aggression always masks other problems. As proven by shows like Into the Woods, Fairy Tales can be elaborate philosophies about human relations, and Beauty and the Beast is obviously about marriage. Belle abandons her beau to courageously and dutifully lay down her life to save her family. She's neither a martyr nor an idiot. Belle knows full well that her siblings are unworthy of her sacrifice, but her devotion to her father is total. In arranged marriages, hapless daughters prove their devotion by following their fathers' orders and marrying without love; the independent-minded Belle defies her father. Against his wishes, she bravely journeys into the unknown. Her perilous stay at the castle is not unlike a marriage that's gotten off to a bad start. Belle is repulsed by the Beast, and he's frustrated and stymied by his inability to dominate her. The Beast has horrid manners and habits, and Belle is at first distant and closed-off. But theirs is an honest relationship. He confesses his angst, and she does not hide her fear and disgust. Whenever people are truly open and honest great things are possible -- even monsters can be loved. When The Beast risks all by allowing Beauty to leave on just her parole, Beauty and the Beast becomes as complex as any story about human relationships. He gives his prisoner the opportunity to be free and to destroy him, should Belle choose. Should the Beast die, a fabulous treasure will also be hers, riches that could solve all her family's worldly problems. Beauty would have a good argument to do away with the monster, who, after all, did her family great harm ... it makes complete sense for her to become Jack the Giant Killer. How often do mortals get the opportunity to defeat magical monsters? But Belle has character, and The Beast's willingness to gamble on her word inspires greater notions of loyalty and commitment. The Beast may be a monster but he has a nobility that goes beyond the entitlements of a class system. Only when the commitment is such that partners are willing to lay down their lives for one another does a marriage become a marriage. That's the beauty of a marriage, this selfless / selfish dream.

Criterion's Blu-ray of Beauty and the Beast is a handsome rendering of this artfully constructed show, with its many intricate sets and costumes that benefit greatly from the added detail of High Definition. It was one of the first Criterion DVDs released, and one of the first to be remastered with a digital clean-up. This edition is even more sparkling. No more dull gray on black 16mm prints! Beauty and the Beast opened with a normal set of titles when imported to the US. This edition restores an amusing original opening: Jean Cocteau himself scribbles the first few titles on a blackboard, while we see the backs of Marais and Day as they erase their own names. Nothing earth-shattering, but a pleasant touch returned to its original state.The video extras are all repeats from the 2003 edition. Two commentaries are offered, by critic Arthur Knight and author Christopher Frayling. Phillip Glass's opera, which synchronizes his music while voices sing the dialogue, is interesting enough but has a droning quality consistent with other Glass scores. I like the music, but it seems to flatten out the moods of the film. Screening at the Majestic is a very good retro docu where cameraman Alekan and stars Marais and Mila Parély revisit the locations for the picture, a country chateau and a bizarre statuary garden that were brilliantly used. More detail about the cinematography comes from a French TV interview with Alekan; and another television short subject has the makeup man describe how he turned Marais into The Beast. The film restoration demonstration is even more detailed than on earlier discs. The insert booklet retains an essay by Jean Cocteau and adds another by Geoffrey O'Brien, as well as some notes by composer Philip Glass. Not carried over is the text of the original fairy tale included on the 2003 disc.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Beauty and the Beast Blu-ray rates:

Footnotes:

1. Admitting some kind of relationship between poetry and movie special effects, Cocteau's much earlier Blood of a Poet is first and foremost a trick film, one that cleverly recognizes that a still pool of water might be a mirror, and that even if audiences realize a trick is being used, they'll still respond to grotesque distortions of familiar objects. In his later Orpheus films, Cocteau set his earlier magic in a new kind of fairy tale occurring in recognizable reality, with settings that illustrate contemporary preoccupations. The charred limbo that is 'La Zone' is easily seen as representing not just the Underworld, but the ruins of Europe, or perhaps a world poisoned by a nuclear war. Cocteau's fantasies immediately conjure the poetic underpinnings of many science fiction and horror films. It's a sensitivity that makes otherwise opaque movies like Alphaville and Eyes Without a Face pop with complete clarity.

2. Proving that technical proficiency in a monster un-rooted in character and theme, is never good enough. Jack Pierce's The Wolf Man is a masterful creation

- in stills. In the movie, the monster isn't much like a wolf, and has little connection with Larry Talbot. Jack Kevan's The Creature from the Black Lagoon is an incredibly well-designed creation, instantly accepted by audiences, that was never given a suitable story to inhabit. The Gill Man 's penchant for kidnapping the heroine has little bite beyond rote formula: what does a fish want with Julie Adams? She doesn't even know how to spawn.

3. I think of this a lot when I read of people sentenced to ten years for possession of tiny amounts of drugs, or mentally disturbed people being executed in the Texas death penalty treadmill. Draconian justice immediately points to the law as corrupt, not the criminal. Our society needs to spend time with some good fairy tales.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2010 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||