|

|

|

|

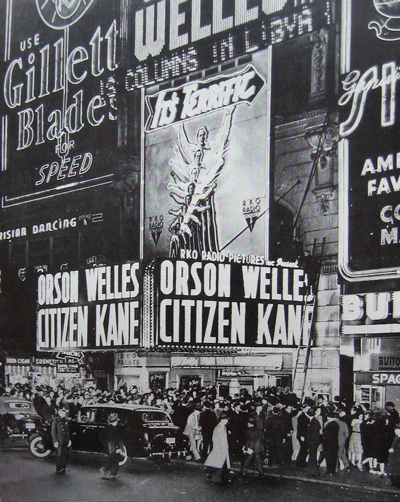

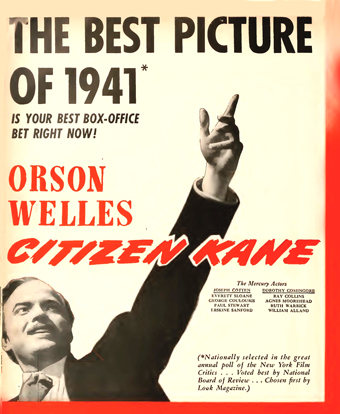

His career littered with half-completed and broken projects, Orson Welles became the original Hollywood outsider, forever scrambling and hustling for completion funds. Yet he defied the odds by bouncing back several times with good movies. At the beginning of his film career, starting at the top at RKO, Welles' problem was indecision; some observers doubted that he would get a movie off the ground at all. He was dissuaded from making Conrad's Heart of Darkness and dropped a thriller called Smilier with a Knife as well. Welles' monumental Citizen Kane instead tackles the enormous puzzle of American identity that Orson Welles seemed to personify: genius, ambition, folly. Emerging from a spoiled childhood to make his mark assaulting the status quo, Kane resembles the nation even more closely than he resembles Orson Welles, the boy genius that overwhelmed New York. With his brash manner, fresh ideas and his willingness to risk everything, Welles was convinced that his force of personality, sheer bluff and raw talent would pull him through.

These days anybody whose ideas can turn a nickel into a dime will find open arms in the business world. Welles took RKO at its word when he was handed the keys to the studio, with the promise to make something brilliant. Daring innovation had worked on Broadway and in the radio, and now the movies were the next horizon to conquer. Welles dodged the naysayers in Hollywood -- who had been making talking pictures with one set system more or less for ten years -- by approaching his movie as art and assembling a dream team of technicians. Knowing the value of personal control in an established system, Welles imported cinematographer Gregg Toland and his entire camera crew to RKO. The actors were his own from New York, and the crew was under his control as well. The front office was something to be kept in the dark and fed misinformation. Denied a final-final start date on what would become Citizen Kane, Welles filmed elaborate "tests" that turned out to be usable scenes for the film. This of course sounds exactly like the kind of stunt Charles Foster Kane would pull. Welles knew that winning over the front office was at best a hollow goal, and that the final result would determine his future in Hollywood: "People will know who is responsible." Meet young Orson, the most daring tightrope walker ever to perform at Gower and Melrose. The first thing film students hear about Orson Welles is that he made the greatest film in history when he was 25 years old. For ambitious would-be filmmakers, that benchmark is like a biological clock: I'm 22 and I haven't got my first studio contract yet!" The shocking thing about Welles is that his masterpiece shows few of the usual signs of immaturity. Welles had lived largely among sophisticated adults since early childhood and could dominate most any adult discussion. Herman J. Mankiewicz has an equal or greater claim on the script for Kane, but as Welles reshaped the material to his liking, it is his presence that we "feel" in every film frame. The famous Welles quote about the "biggest set of trains" mischaracterizes the director's creative approach. Welles and Toland took pains to make every sequence its own mini-movie of filmic innovation -- reinvigorating every school of film theory established to date. Some Hollywood detractors were surely reacting to things they didn't understand, which they called meaningless film tricks. Take the screaming parrot added as a jarring scene punctuation. There are now as many analyses of that parrot as there are books on Citizen Kane. But the parrot isn't a gimmick or an extraneous gag for its own sake -- it's part of the delirium of the sequence. Kane sees Susan's exit through a dislocated set of doors, and a forest of reflections expresses Kane's 'shattered' mental state (Kane's last image in the movie, I believe). Critics are just as apt to misinterpret technical issues in films. I've read and heard in commentaries the howler that Kane was the first Hollywood film that showed interior ceilings (!). We're still not sure whether or not any of Welles' idea of performing to audio playback remains in the film; some sources say that radio-inspired experiment was scrapped in earlier Heart of Darkness tests and others say it lingered on. We read that Gregg Toland hated opticals, but Kane employs every trick that Linwood Dunn could manage on his optical printer. We see not only precise dissolve transitions (many with unusual, expressionist hold-out mattes) but entire scenes that are nearly undetectable matte paintings, with only part of the frame consisting of live-action segments.

The visual style of Kane is Welles' attempt to create a 'super theatre' dramatic experience. The movie isn't expressionist in the orthodox sense but every angle is stylized; he acknowledges that his visual ideal is John Ford. Welles loved deep focus shots, so Toland used wide-angle lenses and poured in light from arcs normally used for Technicolor work. Thus we get a film where every shot is composed in depth. If the characters and writing of Kane were at a lesser dramatic pitch many of the angles and camera moves would come off as forced. But the heightened elements are in balance. Welles demands that each shot express the meaning of a scene, not simply record actors and motion. Kane's so-called baroque style is really Welles' "Declaration of Principles": everything up on the screen is both important and personal. Welles' core of actors includes colleagues from his radio days in New York. Among them only Joseph Cotten has the looks of standard star material. I'd imagine that viewers were surprised to see these people undergo several complicated make-ups to represent different ages, and note that Welles' cast round-up at the finale shows the actors in old-age makeup where possible. Cotten and Welles end up wearing glassy oversized contact lenses to make their aged eyes look rheumy, an effect that works extremely well. The most stunning age illusion is provided by Everett Sloane, whose Mr. Bernstein outlives everybody else even though he doesn't look all that young when we first meet him. But Sloane was only 30 or 31 during filming! I marveled at the actor's undetectable bald cap makeup in his later scenes. Then I was told that the actor had simply shaved his head. A good magician can make us imagine more movie magic than is really there. For many first-time viewers Citizen Kane's multiple flashback structure can be confusing. I always become a little disoriented when Kane loses The Enquirer in the '29 stock market crash -- why didn't he retain his beloved newspaper by selling his ocean liners or something? Even viewers accustomed to stories told out of sequence can lose their way when the narrator relating the flashback recounts events that seemingly took place when he was absent, Joseph Cotten's character especially. Only later does it seem logical that Jedediah would have pieced together parts of his memories from 3rd party sources. Detractors leap to proclaim that Kane's final word "Rosebud" was spoken when Kane was alone, without a witness to tell the tale. This is refuted in the film when Paul Stewart's Raymond relates the event in the first person: he was apparently there at Kane's side when he died. We are also surprised at how many writers claim that we never see the face of Mr. Thompson (William Alland), the reporter chasing down the secret of Rosebud. Alland doesn't get a high-key close-up, but we see his features very clearly in many shots. What is consistent to every scene throughout the film is the focus on Kane's psychology, the mindset of a 'great American' who finds wealth and power and thinks he can stake a claim on the public's love as well. Kane finds that impersonal adulation is an illusion, and drives away his loved ones by demanding their love on his terms. Woefully blind and naïve in his personal dealings, the cocky entrepreneur betrays his first wife, turns on his best friend and drives his second wife to the brink of insanity with his grandiose, unrealistic demands. Kane appreciates art by acquiring it, and effectively withholding it from the rest of the world; his awful selfishness in all things is matched by an infantile innocence. Orson Welles was also deprived of his parents at an early age. He paints Kane as a man given the world but unequipped to understand his own feelings.

It's too easy -- auteurish-easy -- to say that Orson Welles' later films merely revisit the themes of Citizen Kane. This first movie is packed with so many ideas that parallels would pop out if Welles had made Republic Serials. But one persistent Kane idea is that an individual's life is not a puzzle that can be solved with a few observations and clever conclusions, the kind proffered by magazine biographers on a deadline. Whenever Welles settles on a major character of power or authority, the same question of "knowability" arises. Who was this man, really? How can we assume we know anything about another person, based on what we hear or read second-hand? The leading character of Welles' quirky suspense thriller Mr. Arkadin is a man of mystery that Interpol cannot pin down. Arkadin thinks he can stay ahead of the game by killing everyone he ever had dealings with, methodically erasing all memory of his criminal past. His scheme to rewrite his own biography backfires, and he ends up forced to erase himself. The gross, corrupt cop Hank Quinlan of Touch of Evil seems capable of unlimited villainy. Yet the testimony of his long-time associates makes us accept the idea that he was once a great policeman and the most important person in their lives. Marlene Dietrich tosses off the line, "He was some kind of a man... What does it matter what you say about people?"... in much the same way that Kane's Raymond shrugs off Mr. Thompson's probing questions about Rosebud. Speeding through what was until 1941 a charmed life, Welles already seems aware that he is as incapable as anyone of figuring himself out. Readers have been grousing for a Blu-ray of Citizen Kane for years now, and Warner Home Video has come through. The stable image gives us a full gray scale that enhances scenes like Mr. Thompson's visit to the Thatcher Library, which really needs some airborne dust suppression. Owners of the ten year-old DVD can finally relax, as the flaws peculiar to that disc have been fixed. Warners' box copy tells us that the restoration began as a 4k scan. The Rain in KANE stays Mainly on the Pane. Citizen Kane was one of the first movies to be digitally deconstructed, cleaned up and enhanced for DVD, by a company that was reckless with its pixel-scrubbing tools -- the famous lamented flaw in the earlier DVD special edition is the erasing of the bright raindrops hitting the window behind Mr. Bernstein in his Manhattan apartment. The rain is now back where it belongs. Citizen Kane is a film we all saw on 16mm prints from Films Incorporated, which were sometimes not good enough to judge various effects -- the higher contrast indeed erased all detail from the many human figures that stand in shadows. Now we can judge every shot in the picture, with an image that finally gives clues to how scenes with extreme deep focus were accomplished: some are clever matted double exposures. The giveaway is when the extreme foreground and the extreme background are in focus, but the middle distance is not --- something that doesn't happen with human vision.

Kane on Blu-ray comes in two deluxe packages. This 70th Anniversary Ultimate Collector's Edition is a bit less expensive than a package that also includes a DVD of what should rightfully be called "The Magnificent Ambersons: The Remnant". The Anti-Welles backlash by the new RKO regime ripped Ambersons to pieces, so that after the 2/3 mark it no longer resembles a Welles film, one that might have been the equal of Kane. I can't recall any other sound film so thoroughly trashed by its own studio, and I don't believe Robert Wise's contention that it 'didn't work for an audience'. The country post- Pearl Harbor embraced a lot of screwier pictures, like the similarly American hypocrisy saga Kings Row. (I include here without further comment a 1942 trade-paper notice that RKO has decided to delay screenings of Ambersons.)

A thick card box embossed with a picture puzzle motif contains a disc holder with three discs: the Blu-ray of Kane and two DVDs. The Battle over Citizen Kane is the 1996 American Experience docu that sees Welles' film solely as an attack on William Randolph Hearst. We get a lot of fascinating history about the two men, with the idea that their backgrounds and life-aims were similar. The parallel only goes so far. What the docu doesn't convey is the likelihood that Welles underestimated the impact of fashioning Kane with some qualities of Hearst in mind. The radio bad boy who perhaps hoped that a 'little panic' from The War of the Worlds would boost his personal popularity, clearly poked fun at Hearst with the idea that he could hide behind a deniability factor. Whatever the truth is, Welles could not have known the trouble his recklessness would stir up. The "unknowability" factor makes the second DVD, the 1999 HBO movie RKO 281 into an extended curiosity. A cleverly assembled drama about Welles' various run-ins with Hearst during the making of Kane, the movie can't be more than a wild stab at the truth no matter how well it was researched. Liev Schreiber, James Cromwell, Melanie Griffith and John Malkovich star. The other Ultimate extras are an attractive souvenir book containing many photos and various factoids about the show, a reproduction of the original premiere program, a stack of lobby card reproductions and a sheaf of various studio memos of note. The final verdict on Warners' Kane package is "knowable": the legions of fans that worship this film finally have a decently screen-able copy. You know, the necessary tool with which to spread the word about the "greatest film ever made".

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Citizen Kane Blu-ray rates:

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2011 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||