|

|

|

|

The cult of Sam Peckinpah has waned of late, in part because the intervening decades of graphic action films have long since eclipsed his excesses of violence. Beginning as a fine writer, Peckinpah reworked the definition of the American western and eventually made some major statements about screen violence. There's no denying that his masterpiece The Wild Bunch is torn between character study and a glee at blowing away audience preconceptions of what real killing is like. Despite the fact that he downplayed its role, as Peckinpah's career self-destructed violence eventually became his only stock-in-trade.

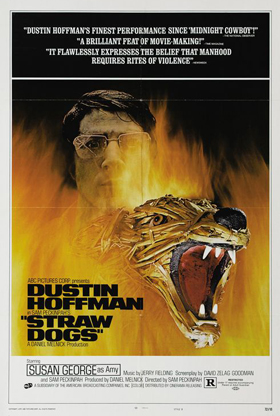

After cleaning house with the Western traditions of John Ford, Peckinpah's next major move was to England for a particularly violent contemporary fantasy. 1971 was the year that the old production code taboos were really broken in films that weren't necessarily exploitative in nature -- pictures like The Devils and A Clockwork Orange. Unfettered by good taste or studio conventions, Sam fashioned a nasty tale that waved male rage like a gauntlet, as a challenge to the universe. Some of Straw Dogs is just as poorly judged as Peckinpah's later, patchy work, but nothing before it matched its sheer power to rev up audience bloodlust. This is inflaming my Territorial Imperative! Even in 1971 we knew that the story was rigged to place an ordinary, non-violent intellectual in the position of embracing violence as the solution to his problems. To work in quiet seclusion, meek mathematician David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) has taken up residence in the small Cornwall town where his young wife Amy (Susan George) was raised. He immediately becomes the butt of jokes for the local toughs, who see him as a milquetoast. They also regard the mildly provocative Amy as fair game to prove their macho superiority. Immature and frustrated, Amy encourages the attentions of the louts who have come to work on the Sumner roof, precipitating a series of harrowing events -- of which a brutal rape is only the beginning. Amidst it all, David discovers his own sense of primitive outrage, and his own acumen for violence. Savant saw the shorter (by five minutes) American cut of Straw Dogs at least five times on its release in 1971; I had just become a life convert to The Wild Bunch and was eager to bolster my longhaired, unemployable film-student impotence with a dose of Peckin-testosterone. I soon grew weary of the glut of films that attracted audiences in need of violent catharsis, but the screenings of Straw Dogs I remember were marked by genuine interactive bloodlust. Packed theaters shouted at Dustin Hoffman to blow people away. I remember hearing cries of, 'Kill the bitch!' more than once. In his earlier career Peckinpah had impressed critics by directing ordinary scenes with uncommon sensitivity, and effortlessly managing tension and conflict. He earned some of his highest praise for television shows like The Westerner and the TV play Noon Wine. To its credit, Straw Dogs quickly establishes a sharp dramatic edge that grabs the attention and holds on tight. The introduction of the basic situation in the Cornwall town, with its jobless malcontents and bitter pub crawlers reacting with predictable meanness to the intrusion of wimpy American Dustin Hoffman, is economical and effective. Susan George's insolent cheap-tease Amy Sumner may inflame feminists, and Peckinpah and scenarist David Zelag Goodman (The Stranglers of Bombay) don't hold back in their depiction of such a destructive female character. PC or no PC, created by male oppression or not, Amy Sumners do exist, and their taunting can indeed cause havoc. Straw Dogs even offers us an Amy Junior character, a younger local tease who clearly sees David's wife as a role model, a local girl made good. In the first of the screenplay's portentous symbolic scenes, the two women are introduced carrying a giant iron man-trap, the kind used to catch poachers. Their provocative teasing is associated with the village kids playing in a graveyard, continuing the Buñuel- Los Olvidados link to The Wild Bunch: children and stray-cat women are by nature neither innocent nor virtuous.

Straw Dogs boils twin pots of discontent. Troublemaker Amy stirs up bad vibes at home with her taunts and jabs at David's lack of macho possessiveness. A generic 'intellectual' conveniently symbolizing liberal non-violence and tolerance, David is the repository for everything Peckinpah sees as lacking in modern Americans. He's a cheek-turning wimpus who doesn't understand that the 'older' (and by Straw Dogs' thin logic, more primitive) Cornwall culture operates on an Alley Oop level of brute force. Amy is 'modified' by symbols as well. Repeatedly compared to the cat, she saunters and flaunts herself in petulant protest. The other source of tension in Straw Dogs is the sharply rendered social situation, in which unemployment and surly resentment are the normal state of affairs. An editor friend was in a small Irish town in the late 1990s, and dated a local girl. The local 'lads' let him buy beers at the pub and then showed their contempt by battering his rental car to an un-drive-able pulp while he slept. Peckinpah's quaint town has its sheriff-like constable and its ineffectual churchman, but neither can control the idle young men ready to lash out at strangers and take what they want. Even if Amy had handled the situation better, she and David might still expect trouble. As it is, her encouragement of Charlie Venner (Del Henney) invites sexual violence. Charlie's friends vary in their hostility and charm. One is a 'ratter' who goads the others on. They have backup in the person of drunken Tom Hedden (Peter Vaughan), an aging beast of a man. The maladjusted Tom baits the constable and threatens to brain the bartender over a pint of spirits. Like papa Clanton in My Darling Clementine, Tom gives the younger men an authority figure to help them set aside their better natures. They don't need the blood oaths of the Hammonds or the Confederates of Major Dundee -- they're an informal group of similarly resentful louts. The second act shockeroo is a rape scene that, even when trimmed, was rougher than anything yet seen on American screens. Amy clearly wants Venner to attack her, a nasty acknowledgement that some women (sigh) just plain Ask For It. She pays dearly when a second rapist moves in to violate her anally -- with her previous 'beau' held off at shotgun point. Amy is thus damned thrice over, as 1) a pussy tease (pardon) to poor cuckolded David, 2) a faithless bitch in her open invitation to and eventual welcoming of rape, and 3) the worthless tramp who is given what she deserves in the roughest way possible. Pauline Kael, if I recall correctly, labeled Straw Dogs a fascist film for this scene, setting it next to Dirty Harry as a manipulative counterattack against liberal values. Unfortunately, violence and sexual sadism were a winning combo that year.

The action predictably spirals to a bloodbath. The actual trigger turns out not to be Amy but Henry Niles (David Warner), a mental deficient and town fool. Like Steinbeck's Lennie, Niles accidentally kills a young girl. The necessity of protecting Niles from Tom Hedden's lynch mob provokes American Sumner to prove himself by taking a moral stand for rigid righteousness. David Sumner defends his self-identity, first with stubbornness and then with a grave oath, the kind that in Peckinpah's world can lead only in one direction: "I will not allow violence against this house!" Hedden's mob lays siege to Sumner's strong-as-a-castle stone house. David learns the truth about Amy's connection to the boys outside when she tries to let them in. She doesn't care if they kill Niles. Dragging Amy upstairs by the hair,

The bloodbath that follows is one that every Anglo-American male has entertained when contemplating riots or civil insurrection. David has no firearms but he's got a massive door that can't be battered in, lye to boil, and a number of other improvised weapons. The entire audience cheers for this Lochinvar as he battles foes outside and an intimate traitor within. The stage is set for a killing spree we can all get behind... as in United We Stand. The ending is a hip combination of directorial strength and weakness. David takes Niles to the authorities, mumbling the psuedo-enigmatic dialogue line 'I don't know where home is anymore'. Amy, branded as the reckless sexual firebug responsible for all the carnage, gets left behind with a houseful of stiffs. Straw Dogs' excellent character direction is periodically undercut by Peckinpah's new tendency to lean on obvious symbols and lame directorial touches, such as the 'clacking ball bearing' novelty item on David's desk. As David and Amy argue, it clacks away as a detail in the frame, an okay echo of their conflict. Peckinpah ruins the moment by later cutting to it for a close-up, grabbing us by the back of the neck and pushing our noses into his symbol. Bad form, and the sign of a director who has now decided he's an 'auteur'. But this violent film honed Peckinpah's montage cutting to delirious extremes. When the distraught post-rape Amy sits with her husband watching a miserable church variety show, Peckinpah and his editors inter-cut the performances onstage with violent flashbacks to the rape. Adding reaction shots of the sickened Amy, the tempo rises until the tensions in the crosscut scenes bleed into each other. It's showy, but it works like a charm. 1 The editing will not seem inordinately fast today, when unintelligible flash cutting is the norm for action sequences. In 1971, the dynamic flow of violence over the course of a full reel was hypnotizing. The mayhem is more intense and less lyrical than the aesthetic ballets of death in The Wild Bunch. The concluding siege still carries a solid wallop, because the audience has been so thoroughly primed to anticipate intense action. Today's wall-to-wall escapist action pictures can't get this kind of reaction, even when they're far more violent. We feel each physical outrage personally. The immediacy of a drunk getting his foot blown off, and the sickening notion of being snared and wired to a window casing lined with jagged glass, still carry a jolt. 2

Straw Dogs is Peckinpah's last truly valid violent film. It is ugly and morally questionable, but it's still Peckinpah working at the height of his powers, expressing his malcontent's outrage in an interesting fashion. By all accounts Peckinpah was a great talent who could easily have parlayed his cult popularity into a more prolific and rewarding career. Drugs, drink, paranoia and an inability to get along with people short-circuited all that, leaving us to contemplate his masterpieces, embarrassments, and the ruins of a few pictures that can still be restored. Set to debut soon is a Rod Lurie remake of Straw Dogs, relocated to the American South. MGM / Fox's Blu-ray of Straw Dogs gives us a clean encoding of a film shot on overcast days, featuring dark skies and the muted colors of Cornwall. The precise transfer brings out the finer qualities in the cinematography of John Coquillon, previously noted for Witchfinder General and several other A.I.P. made-in-England thrillers. Coquillon's interiors never seem artificially lit, a quality he shares with the celebrated Nestor Almendros. Possessors of the now- OOP Criterion DVD of Straw Dogs would be wise to hang onto it, for its impressive complement of extras that include a discrete Music and Effects track and an 82-minute documentary on the director. MGM's no-frills Blu-ray includes only an original theatrical trailer and a pair of TV spots.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Straw Dogs Blu-ray rates:

Footnotes:

1. Peckinpah intended to use this cutting pattern for the legendary deleted opening to Major Dundee, where an Apache raid interrupts a frontier Halloween party. Kids run about dressed as ghosts and Indians, as adults carouse and soldiers sing, all inter-cut madly. Glimpses of very-convincing Apache makeup are also seen, and then it is suddenly revealed that real Indians have infiltrated the party. The audience is meant to be as surprised as the rapidly slaughtered homesteaders and soldiers. 2. Feature film editor and pal Steve Nielson found another big difference between the fast cutting here and in contemporary films. Peckinpah's violent cuts use mostly static, often locked-down angles. There is camera motion on masters, yes, but not the 'every cut is a movie unto itself' Michael Bay ethic. This can be good when the angles are rightly chosen, but a few details of the final battle become confusing. Despite Peckinpah's attempt to spell everything out clearly, we're not always sure how many assailants are still functional, where they are, or who they are.

Keeping track of who's dead and who's still alive is made more difficult by spotty continuity. Check out the final victim, who collapses into a heap against the wall, next to a chair, right opposite the staircase. Less than thirty seconds later, we see a wide view of the whole room from the top of the stairs. The chair and the wall space are there but the victim is missing. Admittedly, the masterful siege sequence keeps 1,001 other scene elements perfectly well organized. 3. The British Board of Film Classification has written up an interesting, if self-congratulatory, Case Study page on Straw Dogs.

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with reader input and graphics. Also, don't forget the 2011 Savant Wish List. T'was Ever Thus.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||