|

|

|

|

H.G. Wells' Things to Come has long been denied its proper respect despite being one of the most impressive science fiction spectaculars of all time, written and guided by the man who practically invented the literary subgenre of science fiction. Its producer Alexander Korda assembled a creative 'dream team' to realize Wells' vision. There's been no movie in film history quite like it, and its commercial failure sidelined big-budget, intellectually progressive filmed sci-fi for over thirty years. The expensive Things to Come was met with such an unsatisfactory public response that it was cut several times from its original version (reportedly 130 minutes in length) and the trims lost or abandoned. Quality viewing copies of even the shortest version simply aren't out there; and until a few years ago aficionados had to content themselves with patchy, high contrast 16mm prints with audio so rough that some dialogue scenes were difficult to make out. In 2007 Network / Granada released a somewhat reconstructed release with some good extras, especially an "exploded" cut of the film that inserted script pages to fill in missing scenes. Now the Criterion Collection has stepped up with a fully appointed Blu-ray edition. It may be the best Things to Come will ever look, unless a perfect uncut copy suddenly should surface, a la the miracle Argentine print of Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Wells' vision is a sprawling epic. In 1936 (when the film was released) peaceful Everytown (read: London) is bracing for a renewed conflict, which comes in 1940 in the form of massed air raids. A decades-long world war ensues, bringing an end to civilization. Thirty years later, Everytown has barely survived a terrible plague called The Walking Sickness, and is still a rubble heap. Its feudal ruler Rudolph, The Boss (Ralph Richardson) wages primitive war on neighboring fiefdoms to secure the raw materials to revive more sophisticated weaponry. Into this Dark Age lands a futuristic aeroplane. Its pilot John Cabal (Raymond Massey) wears an oversized bubble-headed helmet. Cabal was once a citizen of Everytown who preached pacifism. Now he's an air envoy for a Basra-based technical guild called Wings over the World that is using superior technology to defeat the warlords and make a new start for mankind. The Boss holds Cabal hostage but engineer Richard Gordon (Derrick De Marney), his wife Mary (Ann Todd) and Doctor Harding (Maurice Braddell) steal one of Everytown's antiquated biplanes to summon WOTW reinforcements from Basra: giant bombing planes armed with the 'Gas of Peace'. Conquered without bloodshed, Everytown joins the New Order. Decades of scientific advancements follow, re-engineering Earth into a peaceful technocracy of industry and underground living. A century later in 2036 society has built a giant Space Gun to shoot humans around the moon, but a group of dissident artists led by master sculptor Theotocopulos (Cedric Hardwicke) incites a mob to destroy it. The revolt fails. As the Moon capsule blazes to the stars, John's grandson Oswald Cabal pontificates on the destiny of Man.

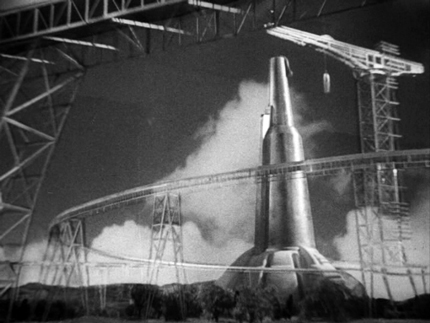

The making of Things to Come is an unusual, complicated story. H.G. Wells had complete artistic control, at least until the film's premiere; his goal was to spread his ideas about what lay ahead in mankind's future. A utopian idealist, Wells made a couple of notable predictions (a London air raid in 1940 is the main one) but was blinded by an intellectual belief in his own infallibility. He thought wars would bring an end to technical progress, when the opposite was true; he believed that the nations of the world would be destroyed in an interminable WW1-type conflict and a subsequent plague, which would bring about a universal revolution run by a technological elite. As Criterion's extras point out, Wells actually tried to lecture Joseph Stalin about needed changes to the Soviet revolution; one can't fault the author for not standing behind his words. The strange irony is that, although Wells despised Fritz Lang's giddy, scientific fairy tale Metropolis, our present future more closely resembles Lang's classed society than the societal nirvana of Wells' epic. Moreover, Wells' antiseptic future now feels like a Fascist state... an idealized, sanitized version of what Germany's Albert Speer might have cooked up, had he worked in glass and super-plastic instead of concrete. As emphasized by scholars David Kalat and Christopher Frayling, Things to Come employed a surfeit of fine designers. The director William Cameron Menzies was also best known as a production designer. Wells expected viewers to be fascinated by his illustrated super-lecture and receptive to his grand ideas. Critics instead lambasted the film for neglecting to engage the audience: Variety's review commented sourly that, "For heart interest Mr. Wells hands you an electric switch." Actor Raymond Massey complained that all his effort was going into selling what was basically a futuristic position speech. It's interesting that a decade later Massey would be at it again, mouthing reams of Ayn Rand's political and philosophical rhetoric for The Fountainhead. Rand had also been given contractual control; both movies are expensive pulpits for their authors' windy oratory. But these considerations cannot diminish Things to Come's near-astounding achievement as filmed science fiction. Arthur Bliss composed his symphonic score in concert with Wells' writing process, using the music as the foundation for major non-verbal scenes. The dramatic terror of the opening invasion fear montage is achieved via editing theories borrowed from Russian masterpieces. The concepts of War and Peace are batted about in graphic text, like signposts in a Jean-Luc Godard film. The movie's special effects are remarkably well designed. State of the art opticals, miniatures, rear-projection and giant sets for a Piccadilly Circus-like city square show the evolution of Everytown through aerial destruction, decades of post-apocalyptic rot and finally its total re-invention as a massive underground wonder city. The Earth's surface is restored as a verdant garden. We see "men's mighty mine machines digging in the ground" to unlock the planet's wealth for "our children's children" (thank you, Moody Blues), a super-engineering episode that assumes that Mother Earth's natural resources are unlimited. We of course aren't told how the population is controlled, or where all the non-Anglo people might be. The 2036 vision of "Utopia Achieved" includes a space program dedicated to the hubristic proposition that mankind's destiny is to conquer the universe. Wells proposes that we will achieve God-hood in the same way that his Doctor Moreau dared to 'evolve' animals into men. Does Cabal want us to become a floating ghostly intelligence, like the Star Child of 2001: A Space Odyssey? Are we not men?

The Space Gun conflict of 2036 is a cheat: Wells raises a debate but arranges for the opposing viewpoint to have little or no credibility. The rebellious artist Theotocopulous irrationally demands an end to progress. He proclaims a lot of stuffy, selfish hogwash while the superior Cabal verbalizes Wells' philosophical quest for the stars, the frontier that gives life meaning. The progressive Cabal is willing to sacrifice his own child and other young people on risky space missions into the cosmos. Poor Passworthy (Edward Chapman) is caught in the middle, just begging for a little peace and quiet. The inspirational final shot of Cabal's noble profile against the stars seems borrowed from the final chapter of Wells' novel The Food of the Gods, which describes a colossal 'new man' as he proclaims his right to conquer without end. The imagery is also uncomfortably close to depictions of racial glory in Nazi art: unyielding Nordic faces seeking perfection in the stars. Things to Come is a feast for the eyes and ears and the brain, too. Many scenes have retained an undiminished iconic power. The massed formations of bombing airships would soon be a normal part of reality, as would huge buildings seemingly designed to make individual humans seem insignificant. Ralph Richardson's Boss rants and raves about 'sovereignty' in 1970, becoming the very image of stubborn brigandage in the modern age. We showed the movie to a college dorm -- in 1970! -- and The Boss was immediately associated with Richard Nixon. Criterion's Blu-ray of H.G. Wells' Things to Come is the most satisfactory video iteration yet of this eccentric classic, using source materials held by the BFI. We only wish that even more perfect and complete film elements were available. The flat B&W image has very good resolution and is free of the rough contrast flutter of earlier copies. Further digital intervention by Criterion has taken out spots and imperfections, and eliminated jitter and jumps at splices. I have yet to hear a really clear soundtrack for this picture. Criterion's notes say that multiple elements were referenced and that a 35mm optical track was the primary source. Although far better than Granada's distorted track, the end result is still a little tubby. All dialogue is exceptionally clear, however. For a good CD recording of the score, I can recommend The Film Music of Sir Arthur Bliss.

The BBFC measured Things to Come at 117 minutes when it gave its censor approval in 1936. Its London premiere reported a 110-minute duration. The standard American cut on the old Image Entertainment disc clocks in at just under 93 minutes. Criterion has the longest version available, at 97 minutes. It reinstates three sequences for American audiences. In the first, Passworthy exits Cabal's house before the first air raid. He praises the war spirit as a merciless program of vermin extermination. The second reinstated scene is the Boss's drunken victory banquet, where we learn that Rudolph has other female favorites besides Margueretta Scott. Unfortunately, this addition does nothing to mend the erratic continuity gaps in the following scene, when Roxana talks with Cabal in his improvised cell. The third bit is a portion of dialogue restored to the old man's history lesson to his granddaughter in 2036. The discs' new extras are truly eye opening. Sir Christopher Frayling's interview-essay on the film's designers discusses Vincent Korda and William Cameron Menzies along with other big names from England and the Bauhaus, whose ideas were either rejected or only tangentially utilized. With all the energy going into the film's design, nobody took responsibility for guiding the performances. Fine actors like Raymond Massey were basically left to direct themselves. A related video piece presents a few concept trials from designer László Moholy-Nagy. He experiments with perspective, shadows, and industrial shapes. A vision of little white squares flipping and moving as if on a loom or an abacus was incorporated into the film's 'Industrial Reconstruction' montage. A later experimental film using Moholy-Nagy's footage looks like a psychedelic widescreen light show. Bruce Eder's visual essay goes over the unique relationship between the film's images and its Arthur Bliss music score. Another extra is an audio outtake of narration for a scripted episode during the plague years of The Wandering Sickness. It is accompanied by one photo, proving that an accompanying scene had been filmed. David Kalat's audio commentary contains the most imaginative, thorough analysis I've heard or read on Things to Come. The persuasive Kalat takes on the complex subject of Wells -- his works, his personality, his personal relationships. Everything relates directly to the film, even the author's real-life romance with a suspected Soviet agent. Best of all, Kalat reaches beyond the technical talk and production personality stories to evaluate Things to Come's philosophy -- how it relates to other political realities and futuristic predictions. I wish that more filmed science fiction were afforded scholarly attention of this caliber. Things to Come is a fascinating vision of a future that never was. The sad truth is that working with H.G. Wells so frustrated Alexander Korda that he regretted making the film, an attitude that began sixty-odd years of cinematic neglect. Criterion producer Susan Arosteguy's extras are a big step forward in the rescue of Things to Come's reputation.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

H.G. Wells' Things to Come Blu-ray rates:

Reviews on the Savant main site have additional credits information and are often updated and annotated with footnotes, reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||