Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

French filmmaker Robert Bresson was a bona fide artistic iconoclast. His ideas about cinema go directly against established narrative conventions. His most frequent theme investigates the notion of spiritual transformation, and his most successful films generate a sense of spiritual mystery. Critic Paul Schrader asserts that for him this transcendent emotional rush was a consciousness-raising, inspirational event. Most films accost us, asking for our involvement. Schrader says that Pickpocket instead recedes from the viewer into its own mystery. If we're intrigued, we move toward it. Many critics consider Bresson's 1959 film Pickpocket to be his best.

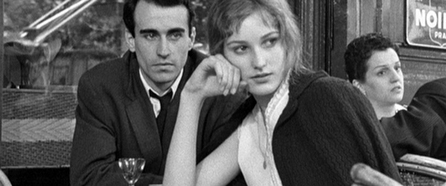

Pickpocket's melancholy loner Michel (Martin LaSalle) is a close cousin to the director's soulful, suffering Diary of a Country Priest. Vaguely referencing a philosophy about privileged 'supermen', Michel considers himself too special to work like others. He cultivates an interest in public sneak-thievery. His friend Jacques (Pierre Leymarie) tries to understand Michel's odd behavior, as does Jeanne (Marika Green), a neighbor of his mother. Michel falls into league with two accomplices led by a particularly talented pickpocket (Kassagi). He is perversely intent on pursuing his criminal life, which can only end in one way.

We tend to champion mainstream film directors that profess a strong personal vision, and Robert Bresson's ascetic vision of film is as extreme as they come. He has no use for movie stars, or even professional actors. As has been repeated in almost every review of a Bresson film, the director refers to his on-screen talent as 'models' and insists that they be non-actors. He asks his cast to behave without expression or theatrics, and employs special techniques to prevent them from performing in an expressive manner. If a 'model' says his line with too much emphasis or meaning, the shot is re-taken as many times as Bresson feels are necessary to 'deaden' the performance into a rote, neutral delivery.

Bresson does not want his actors to project their personalities, but to serve only as a conduit for his thesis. Alfred Hitchcock sometimes talked about using actors as posed 'objects' for his visual schemes, but for the most part he depended on star personalities to bring his films to life, to establish an emotional contact with his audience. Bresson's aims are far less commercially oriented. He controls his actors as a writer chooses words, to connect with the audience only on his terms. No psychological explanation is offered for Michel's behavior. Michel mumbles a few unconvincing words about Nietzschean supermen existing above the common morality, but Pickpocket doesn't fit human behavior into a cause-and-effect dramatic pattern. Michel is essentially as unknowable as strangers we see on the street.

Pickpocket presents realistic people in naturalistic locations -- drab rooms, metro platforms, a racetrack. Sitting in his tiny room, Michel seems absorbed by a vague discontent. When in public he's unable to commit to a few minutes of civility with his friends. He behaves as if he wants someone else to take responsibility for his existence, to change his life. Jeanne looks at him in a maddening way: interested? Neutral? To get her to react he must feed her suspicions about himself. "How do you think I live without a job?" About the only thing we really know about Michel is that he's an egotist, unaware that people around him also feel trapped in their own skins.

Bresson breaks standard narrative conventions, so that we will take nothing for granted. Music is not scored to enhance the drama. Editing rhythms are slower than normal, and cuts don't happen when we expect them to. Shots are naturalistic but actions are not. Michel and his friends move as if employing a conscious act of will to do simple things like turn around, or look in a certain direction. They tend to stare without blinking, as if they were Pod people not quite comfortable in human bodies.

It's possible that Bresson's aim is to get beyond the 'movie experience' so as to involve the viewer more deeply. We're accustomed in films to casually identify with wrongdoers. We project our own thoughts and judgments onto Michel. He's not that different from us. Do Bresson's 'blank' characterizations function as a mirror for the viewer?

The film presents the actions of the pickpockets as strange ritualized behavior, performed like magic. Bresson uses precise, clear camera angles to show Michel first practicing sneak-thief work in his room and then performing it in public. Using the sleight-of-hand skills of professional magician and sleight-of-hand expert Kassagi, we see pickpocket 'touches' carried off both singly and in coordinated attacks. When Kassagi works in concert with Michel and a third man, they're like invisible angels, lifting wallets and rifling purses with magical skill. Is this what Michel wants, to be a phantom presence, moving among ordinary people but existing on a higher level? If so, Michel fails badly. When he prowls on his own in a racetrack crowd, Michel makes eye contact with his victims, seemingly telegraphing his intentions. We feel sure that the victim must be aware of him. Is Michel trying to be caught?

Michel's thievery provides him with the illusion of an identity free of outside control. Yet his struggle to exist independent of other people brings him more fear and doubt. Michel seems capable of appreciating another person only after losing his liberty. Much is made of the climactic scene, with its sudden reversion to conventional directorial tactics: the camera moves sharply forward to heighten an embrace. The final voice-over line is an emotional release for the audience. Yet Bresson holds back here as well -- Michel speaks the final lines as if he were narrating his life in the past tense.

Pickpocket isn't as bleakly pessimistic as Bresson's later Au hazard Balthazar and L'argent. For some it elicits strong religious feelings akin to the director's Diary of a Country Priest. The void at the center of Michel's life seems to call out for the guidance of faith, and some aspects of the final shot validate this interpretation. It is said that Robert Bresson's characters want to transcend the limits of reality, to attain some greater truth. Does Michel experience transcendence? Or does he succeed simply by making a meaningful contact with Marika?

Criterion's Dual-Format Blu-ray + DVD of Pickpocket improves on a very good DVD from 2003, with a sharper and more stable image. The soundtrack seems even more subtle and intimate. Bresson uses lesser-known classical music to strong effect behind his titles and sometimes during pickpocket sequences. The emotion-laden music cue the finish would seem to break with the director's avowed rules of engagement.

Repeated from the earlier edition, disc producer Kate Elmore's extras offer is a variety of viewpoints on Bresson's methods and theories. James Quandt's commentary is a formal analysis that holds the film in proper reverence while pointing out its endless parade of oddities. Quandt notes the apparent disconnect between Michel and his voiceover. He also notes that everything in the movie seems organized in symmetrical pairs -- trips to the racetrack, talks to the policeman, etc. The articulate Robert Bresson speaks on an old French television show; our own Paul Schrader provides a video interview explaining how Bresson inspired him to become a filmmaker. All of these witnesses (even Bresson, to some extent) seem privy to a miracle, the essence of which cannot be communicated through speech. If cinema really is capable of saying things that can't be turned into words spoken or written down, then Bresson is the real-deal cinema guru of them all.

A pleasant TV docu tracks down all three of Pickpocket's 'model' actors, proving that human beings did indeed make the movie. Leading actor Martin La Salle is found living and working in 'obscure fame' in Mexico City. Actress Marika Green also appears in a Q&A session from a 2000 screening. Not to be missed is a French television show excerpt, in which the illusionist Kassagi performs marvelous magic tricks like eating razor blades. He also shows off his pickpocket skills, which are genuinely incredible.

The disc's insert pamphlet essay is by critic Gary Indiana. The film's excellent original trailer makes Pickpocket seem intensely suspenseful.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

Pickpocket Blu-ray + DVD

rates:

Movie: Excellent, if Demanding.

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: commentary by film scholar James Quandt; video introduction by writer-director Paul Schrader; The Models of "Pickpocket documentary by filmmaker Babette Mangolte; 1960 interview with Bresson, from the French TV program Cinepanorama; Q&A with actress Marika Green and filmmakers Paul Vecchiali and Jean-Pierre Ameris; Footage of sleight-of-hand artist and Pickpocket consultant Kassagi, from a 1962 episode of the French television show La piste aux etoiles; essay by novelist and culture critic Gary Indiana; Trailer.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly?

YES; Subtitles: English

Packaging: Keep case

Reviewed: July 28, 2014

Republished by permission of Turner Classic Movies.

Text © Copyright 2014 Glenn Erickson

See more exclusive reviews on the Savant Main Page.

The version of this review on the Savant main site has additional images, footnotes and credits information, and may be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Return to Top of Page

|