|

|

|

|

The most frequent John Ford quote read these days is from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: 'When the legend becomes fact, print the legend'. That idea is unfortunately still very much culturally alive: everybody seems intent on selling the mass public images, or perceptions, or bills of goods. As far as westerns go, John Ford's legends are almost always preferable to the truth. It's hard to argue with the idealized showdown at the O.K. Corral in Ford's wonderful My Darling Clementine. His myth of a noble Wyatt Earp in a gloriously hopeful new West contains all of what was great in 1946 about both the western and America. Previously a liberal icon, Henry Fonda here became one of the greatest western legends ever, a natural hero shy with women, rough on minorities and murder on bad men: all of the inconsistent 'virtues' Americans admire. The Criterion Collection's definitive presentation bests a 2004 DVD from 20th Fox. It includes both versions of this fundamental American western, the 'Zanuck-tweaked' release version and a preview version that expands and mostly improves on the film. Sam Engel, Sam Hellman and Winston Miller's screenplay simplifies history to near mythical terms. When his brother James (Don Garner) is murdered and his cattle stolen, Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) accepts the job as Marshal of Tombstone with his surviving kin Morgan (Ward Bond) and Virgil (Tim Holt) as deputies. Taming the town is fairly easy for the imposing and charismatic Wyatt, with the exception of the reckless Doc Holliday (Victor Mature), a tubercular misfit with a death wish. Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs) arrives from the East to see why Doc hasn't continued to practice medicine and draws the wrath of local strumpet Chihuahua (Linda Darnell), a saloon singer with a heart of gold. But Chihuaha is also carrying on a relationship with the no-good Billy Clanton (John Ireland). His brothers and father Old Man Clanton (Walter Brennan) are the villains responsible for Wyatt's troubles. It's only a matter of time before more blood is spilled at the O.K. Corral.

Anybody who thinks Henry Fonda is cool in Once Upon a Time in the West needs to see My Darling Clementine: without this context it's impossible to gauge the depravity of Fonda's character in the Sergio Leone film. It's a shame nobody recorded Ford's reaction to Leone work, or Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch. If the cantankerous old director was even seeing other people's movies in the late '60s, he would probably not have given his real reaction anyway. We judge the 'real' West by the most convincingly realistic westerns available, and John Sturges' 1967 Hour of the Gun is still the most persuasive version of the 1881 shootout between the Earps and the Clantons. Tombstone was a political battleground between various factions, with the untrustworthy Clantons buying influence on one side and the ambitious Earps abusing appointed law enforcement jobs on the other. When they finally did battle at the O.K. Corral (described in some quarters as an 'Earp drive-by') it's been reported that both factions carried arrest warrants for men on the other side. The Rule of Law requires consensus, and when the most powerful players are at loggerheads real law tends to get left behind. Ford reportedly once hired the real Wyatt Earp to consult on a silent film and claimed his shootout was authentic, which doesn't prevent My Darling Clementine from being a highly entertaining total fiction. But skewed history teaches us about the limitations of our own myths. Fonda's Earp is more than just a generic good guy. He's intrinsically noble, fair, playful and desired by women. His notion of justice is highly discriminatory. He became Marshall after seeing the need to kick a drunken 'buck' out of Tombstone with the admonition, "What kinda town is this anyway, sellin' liquor to Indians?!" It gets a big laugh even as we know that most American towns have traditionally defined law and order as keeping various minorities on a short leash.

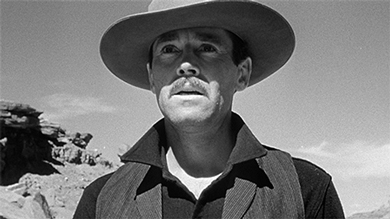

Once on the job, Wyatt occupies the laconic caretaker role that Ford endorsed until his awkward 1960s westerns. Henry Fonda is all gangly appeal. He uses the same deliberate but graceful walk that would later seem so menacing in his Leone film. When bored he balances in his chair, making his heels dance on the porch support. Ford would later use the same image as shorthand for corruption, through James Stewart in Two Rode Together and Cheyenne Autumn. 1 Enter the wholesome, clear-eyed Clementine Carter (Cathy Downs, later of several notable Z-grade Sci-Fi pictures) and Wyatt turns into a tongue-tied kid with his heart in his throat. This was the vision of clean-cut masculinity for which America pined in 1946, when many of its men were war veterans in need of an uncomplicated vision of life. The Eastern, cultivated, white-bread Clementine contrasts strongly with Tombstone's 'red-hot chili pepper' Chihuaha. This classic dramatic model splits the hero's allegiance between the dark good girl and the lighter bad girl, defined along racial lines. No matter how innocent she may be, the bad girl dies or sacrifices herself and is denied the love of the hero. The good girl remains virginally optimistic, un-fazed by her competition and unaware that her high-toned airs and correct racial pedigree make her a shoo-in. Poor Chihuaha is Doc Holliday's anytime girl and doesn't even rate the time of day from straight-arrow Wyatt. He dunks her in a horse trough and threatens to 'send her back to the reservation, where she belongs.' Her background is of no regard. It doesn't seem to matter if she's Mexican or Apache in origin. Poor Chihuahua takes a bullet for her loyalty to the binary hero, and is afforded tenderness and sympathy only when she's safely at the point of dying. 2

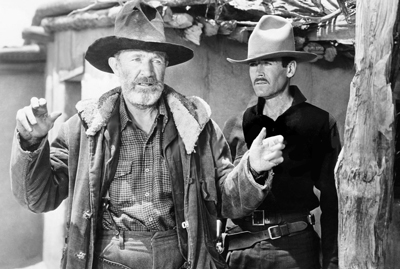

Other films often position Doc Holliday as Wyatt Earp's conscience, but in this film he's his darker half, cleverly used as a red herring for Wyatt's suspicion of Who Done Him Wrong. Together they form a classic binary character of the kind favored by Sam Peckinpah, with each trying to understand the other's contrary idea of chivalry. Holliday is promoted to surgeon status, a step up from the dentist he really was -- in the 1880s, much dentistry was akin to legalized mutilation. Victor Mature's Doc is one of the actor's better performances. John Carradine had played another Southern outcast in Ford's Stagecoach. Holliday's crude domination of Tombstone makes him a formidable opponent for Wyatt, but for classic western cool he can't touch Carradine's mysterious 'Black Sheep aristocrat. Normally the silent type, Ward Bond's Morgan whoops it up with a horselaugh when amused by Chihuahua. Brother Virgil (Tim Holt) remarks that he can almost smell the honeysuckle, to which Wyatt laconically replies, "Nope. It's me. Barber." Of course, top honors for essential wisdom fall to J. Farrell MacDonald's bartender, Mac:

Wyatt: "You ever been in love?"

Another reason that My Darling Clementine is assured a place in western lore is the "West As Garden" theme first proposed by film critics in the late 1960s. Fordian Western heroes are often painfully conscious of their place in the creation of a new society that will grow a garden in the desert, free of Eastern corruption and the inconvenience represented by hated Indians and scalawags like Liberty Valance. "Someday Texas will be a fine place, even if it takes our bones in the ground to make it happen," is the sentiment as expressed in The Searchers: Tombstone is a potential frontier Utopia.

Clementine has Ford's purest and most evocative statement of the "West As Garden" theme. Freshly poofed and powdered at the Bon Ton, Wyatt's Sunday morning path just happens to cross Clementine's. A square dance will take place at the partially built church. Wyatt takes Clementine's arm to walk to the bare platform. A shadow moves across the Earth, indicating the presence of God watching over them all. The charming invitation of fiddler Russell Simpson -- "Make room for our new Marshall and his Lady Fair" -- caps a scene of western Nirvana: an American knight and his damsel in perfect harmony and peace. Small wonder that Sam Peckinpah darkly referenced this scene for the opening of his The Wild Bunch. 3 My Darling Clementine's socko gunfight finale is only the finish for a string of direct violence atypical for John Ford. Usually lovable, Walter Brennan's unredeemable villain shoots people point blank in the back. His sons are a group of sullen louts, even John Ireland's oversexed Billy Clanton. Clanton's key advice to his boys, underscored with a horsewhip, is "When you pull a gun, kill a man!" To find a more savage frontier family, one must jump into The Hills Have Eyes territory. 4

The Criterion Collection's Blu-ray of My Darling Clementine uses the full capacity of Blu-ray to present John Ford's B&W western landmark at its visual best. On a large screen the film's impact just about equals the experience of seeing it back at UCLA, in an original nitrate print. In film school in the early 1970s, the new UCLA Film Archive was just beginning to go through the inventory of Fox studio prints. As it turns out, the print we saw countless times at UCLA was not the version released to theaters in 1946, or what had been shown on television. In an extra included on the disc, UCLA Film Archivist Bob Gitt performs a thorough comparison of the two versions. The differences are very much like the alternate cuts of Howard Hawks' The Big Sleep. The longer cut is a preview version described as being partway between Ford's rejected cut (a half-hour longer) and Zanuck's final release version. It has a number of interesting extra bits. Zanuck dropped several humorous observations from Wyatt, a scene showing John Ireland with Chihuahua, and bits of business around town. He added dramatic scoring, helping some scenes but not others. Without music, some of the location shots in Monument valley communicate perfectly the still, clean-air feeling of the peaceful desert. One cue sampled for a barroom scene is the cute song Sombrero Blanco from The Mark of Zorro -- we expect Tyrone Power to cruise in, pitty-patting the latest dance step from Madrid.

But the main difference is one we noticed right away in 1973. In the standard cut, Wyatt kisses Clementine in a studio reshoot against a rear-projected backdrop. Darryl Zanuck was reacting to preview cards, but he perhaps also reasoned that a movie about someone darling named Clementine ought to have a kiss in it. Ford's original concept is a painfully chaste

Criterion's extras will attract any Ford fan. The audio commentary is with John Ford's key biographer Joseph McBride. Historian Andrew C. Isenberg gives us a look at the real Wyatt Earp; he talks about other versions but never mentions Hour of the Gun, the most accurate one. Robert Gitt's full versions comparison is repeated from the DVD, and Tag Gallagher follows up with a video essay. A very special extra is Bandit's Wager, a 1916 silent western short in which Ford performs, under the direction of his brother Francis Ford. That's followed by a pair of TV featurettes about the history of Tombstone and Monument Valley, a radio adaptation from 1947 starring Henry Fonda and Cathy Downs, and a trailer. The insert booklet essay is by critic David Jenkins.

On a scale of Excellent, Good, Fair, and Poor,

My Darling Clementine Blu-ray Footnotes:

1. Pulp writer Jim Thompson definitely had an agenda of his own vis a vis the noble image of the American marshall in his acidic crime novels. They often feature rural sheriffs who are outwardly respected lawmen imitating Fonda's unassuming style, yet inwardly are ravening psychopaths.

2. As with his about-face on the Indian issue, Ford would later romanticize

(Mogambo) and lampoon (Donovan's Reef) the 'bad girl.' Finally in Seven Women he clumsily addresses female heroism, scoring points with the masculine character played by Anne Bancroft, while making lesbian Margaret Leighton into a rigid martinet of the type critiqued in his own Fort Apache.

3. In a quaint chivalric gesture, Wyatt takes Clementine's shawl before offering her his arm for their walk. At the start of The Wild Bunch William Holden offers his arm to a lady crossing the street, and takes her shall across his arm as well. Peckinpah's church presence is a hypocritical West Texas Temperance Union. Later, in the midst of the gun battle, Holden's horse tramples another woman. On his way out of town, he finds this woman's shawl snagged in his spur, and throws it down roughly. The appropriation of the moment from Clementine seems to represent Peckinpah's claim for possession of the western genre that was once Ford's. 4. One question for gun-savvy Savant readers: when prepping for battle, Wyatt hands mayor Roy Roberts a shotgun, first shucking the shells from its double barrels. What's he doing, handing his ally an unloaded gun? Or is he removing some kind of plugs from the barrels? Inquiring but ignorant gun nuts want to know. Welcome response from Hank Graham, 12.14.03:

Glenn: What he was doing was something every country kid of 1946 would have understood. You store shotguns, particularly older models, with spent cartridges in them, so that if you inadvertently dry-fire the gun, you won't damage the firing pin. The cartridges he's taking out of the shotgun were spent ones, kept in it while it was in the rack. Best, Hank Graham.

The version of this review on the Savant main site has additional images, footnotes and credits information, and may be updated and annotated with reader input and graphics.

Review Staff | About DVD Talk | Newsletter Subscribe | Join DVD Talk Forum |

| ||||||||||||||||||