"A very New York story"

"A very New York story"

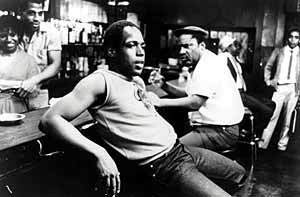

Joe Morton in The Brother From Another

Planet |

June 6, 2002 | At a seminar hosted

by the Tribeca Film Festival,

filmmaker Martin Scorsese lamented the lack of films

set in Harlem. While it may be true that the storied neighborhood hasn't been

used as a setting much since the 70's (a decade which spawned classic films like Cotton Comes to

Harlem

and Shaft), there has been one important exception: John Sayles' The

Brother From Another Planet (1984). As a story, it's an original. As a cinematic

experience, it's uniquely lyrical. And as a statement of a time and place it is

thoroughly specific. With the film nearing its twentieth anniversary The Brother From Another Planet

deserves another look. Luckily it's getting just

that as newly restored prints will be shown at

theaters across the country as part of a huge John Sayles retrospective,

with the director speaking before Brother in at least one venue. (See below for more

info.) Eventually the

restored version of the film will be released on DVD (along with the other early

Sayles film in the retrospective: Return of the Secaucus Seven, Lianna,

and Matewan), a much needed event given the scarcity and low quality of the old VHS releases and the

semi-bootleg DVD out now.

Brother is the story

of a mute alien (Joe Morton) who crash lands his space ship just off Ellis Island.

He finds his way up to Harlem (he seems to be drawn there unconsciously) where

he is confronted by an interesting dynamic: he looks like he should fit in but

he's obviously very much out of his element. The film takes surprising turns as

the brother learns more and more about this new world, while the parallels between

his own experience and those of his new neighbors —

racism, class struggles, crime, drugs —

become crystal clear through his fresh eyes.

The bold, colorful cinematography by a young Ernest Dickerson and the powerful, subtle performance by Joe

Morton (as well as the rest of the uniformly excellent cast) help the film create a mood and atmosphere

beyond both its budget and the mechanics of its excellent story.

As a science fiction film, The

Brother From Another Planet couldn't be more firmly grounded in reality.

Even among independent

filmmakers, Sayles has been able to maintain a level of independence that no

one else whose films are so regularly distributed can match. Income from screenwriting

has allowed him to at least partially self-finance all of his movies. As Sayles

told Cinema Gotham, "The way that we present things is 'Here's the movie. It's not going

to change much from screenplay to final film. We want final cut, casting control

and business control. Are you interested?' We usually get a very nice quick

no, but sometimes people say yes." Granted, it helps if you can wait a decade

to make your film, as Sayles has done several times.

Still, The Brother From Another Planet

came together in a matter of months, while Sayles regrouped after initial investments in Matewan

fell through. Most helpful in realizing this goal was

the MacArthur grant — the so-called "genius" grant — that Sayles received in

1982. The award of $33,000 a year — tax-free — for five years was what enabled him to make as

seemingly noncommercial a film this one.

Recently Cinema

Gotham had a chance to talk with John Sayles about the film, New York, and

the way they worked together to create a fascinating, unique piece of storytelling.

John Sayles on the set of Brother

John Sayles on the set of Brother |

Cinema Gotham:

Your films really move around a lot, more than most filmmakers. But they

use the locations as part of the character and essence of the films.

John Sayles:

Well, I've been to all fifty states, spent at least one night in each. I

hitchhiked around the country when I was younger and I think where you live

affects who you are and how you see the world and vice versa, so I do think

that each place has its own character. It's as things get more homogenized

and that shopping mall culture spreads further and further that they're

a little less different than they used to be. There's that thing that sometimes

a place has a real ambience [as well as] an imaginary one, so with a place

like Harlem, it's like Hollywood. You go to a place like Hollywood and Vine

and there's not much there but there's an idea in people's heads of what

Hollywood might be. For me in The Brother From Another Planet, Harlem

was like that too and that's one of the things that was interesting for

me to get into the film. People, and even some of the black people in the

crew, had never been to Harlem, and they had been warned against it from

their parents or whatever, you know. There's that imaginary Harlem that's

iconic and there's that everyday, people-go-to-work-people-go-to-school

Harlem and the tension between the two of those is some of what the movie

was about.

CG: That

actually brings up something I was going to mention. You start the film

with a series of New York icons: Ellis Island, the Statue of Liberty, the

World Trade Center. And then the first thing you see in Harlem is the Cotton

Club and 125th street. His introduction is, he sees the postcard images

and then the more time he spends there the deeper he gets.

JS: Also,

[I did it] for the audience. He doesn't know what these things mean yet

but for the audience its "Oh, he's coming in through Ellis Island," like

so many other immigrants and there's the Statue of Liberty and all these

kind of iconic things that we think of as coming to America. He has no idea

what they are, so you know there's always that thing of whose eyes are you

seeing the world through. There are two tracks of what the

audience's preconceptions are and what they already know, and what I eventually

want to do is get them to see the world through his eyes. So very shortly

after he comes to shore, even though we know what these things are, he doesn't. So we see the world

through his eyes. And seeing things like, he sees the

crucifix in a window and he thinks "Wow, this is a tough planet. Step out

of line and they nail you to a board."

CG: And immediately

after that he sees the crucifixion-style patting down of the black guy by

the cops.

JS: Yeah,

and what's this green paper [that] you hand to the guy and he gives you

food. I'm always interested in the idea that the audience is already gonna

have what they think they know about the place but also you want to shock

them into seeing it with new eyes. You know, that was the whole Andy Warhol

thing of "I'm going to paint a soup can. We haven't really looked at this

object. It's an interesting looking object that's red and white and it's

a certain shape and we see too many of them to even know what we're looking

at anymore."

"Everyday Harlem"

"Everyday Harlem" |

CG: But I

think the brother senses the magnitude of what he's looking at. I mean,

he hears the voices of all the past immigrants at Ellis Island. On some level he understands that it's

a place of importance.

JS:

Yeah, and the Statue of Liberty is pretty impressive. You know, if you

landed on another planet and there was a statue that big you'd be worried,

"Oh my God, I hope the people aren't that big!"

CG: That's

true. That would have been a whole different movie. The

brother is an interesting guy since he looks like he fits in in Harlem

but he doesn't feel like he fits in. Was any of that alienation in your

own?

JS: You

know, not really. Really more of what it was about to me was the immigrant

experience, and the immigrant experience especially in America. What happens

to the brother is a very New York story. It's a story of assimilation. And

me coming to New York, it was a big city. I'd lived in Boston and Atlanta

before and [New York] was a much bigger city, but for me this was kind of a place that wasn't where

I was going to come and there was no safety net underneath me the way that

if you're an immigrant and you get on a boat or you sneak into the country

without a green card it's sink or swim. It's a very different experience.

So New York was a cool place to hang around and visit but you could always

kind of bounce back somewhere else if you're an American citizen. If you're

an immigrant of some sort and economically or politically your bridges have

been burnt... You know [the brother] is a runaway and he can't really go

back. It's a very, very

different thing. I'm always kind of amazed at how quickly people make some

kind of life there; Chinese guys, Korean people, Hispanic people. You know,

you see people from Africa. There's a bunch of Peruvians who take a bus

every year and sell woven blankets on 14th street and then they take the

bus back to Peru. I'm just always amazed at that, thinking "could I go to

Hungary not speaking a word of Hungarian and survive on the streets?" And

somehow these people do.

Joe Morton and Dee Dee Bridgewater

Joe Morton and Dee Dee Bridgewater |

CG: Those

are two New York experiences: immigrants and Americans, and then there are the people

in the film that he meets that came up in New York. It's their town and

they never get that sense of coming in to town and looking at the immenseness

of it all because they're already inside it.

JS: Yeah,

they're just lost in the flood. The Puerto Rican guy that works in the video arcade, you know, the guys

in the bar who never go below 125th street. They have their neighborhoods.

That may be a little less common now, you know, post-Giuliani, post-Planet

Hollywood, post-Donald Trump, but it's still there. You still see those

people. And you still see the people like the two white guys who take the

wrong subway and they think they're going to a seminar at Columbia [University]

and they end up above 125th street who are kind of the bewildered tourists.

Of course the subways are better now.

CG: Something

you do during the film that you've done many times in your other films as

well, is really utilize all the specific details of your setting. When he

gets to Harlem he's immediately hit with hip hop and graffiti...

JS: And

eventually drugs. This was pre-crack that we made it but they [drugs] were up there.

CG: How do

you feel coming in to a place that has these kind of cues, these details?

JS: Well,

when I hitchhiked around I'd land in a city back in the days when there

were phone booths and phone books in the phone booths — not in New York

because they always stole the phone books — but in other cities they were

still there. You could kind of look in the phone book and figure out who

lived where just by, you know, you took a cross section of where the Baptist

churches were and the Black Panther mosque and you knew where the black

neighborhood was. You could

even look at the names of the streets and probably figure out when you got

into "terraces" and "places" and stuff like that where the rich white people

lived . I'm always very interested in those indicators. Often what I'd do when I'd hitchhike is I'd get

on one street, like in San Francisco, and walk the length of that street

and it might be eight miles and it might take me a day, just to see the

differences. You can certainly do that in Manhattan and Brooklyn and a bunch

of places in New York and you can go through a half dozen neighborhoods.

The crew of The Brother From Another Planet

The crew of The Brother From Another Planet |

CG: I've

done that in a bunch in cities like Atlanta where you just see incredible

changes.

JS: And

then you come back five years later, like in San Francisco. When I first

went there, Haight Ashbury was still kind of very funky but it was still

kind of burned out hippies and stuff like that. I came back five years later

and it was all these gay people who had beautifully refurbished those places.

And now it has a totally different character. The buildings are the same

but they look different on the outside and totally different people were

living there. Some of my movies are about why that happens and how the people

that actually live in those houses don't know that it's happening when it's

happening.

CG: How do

you think the film looks now? New York looks very different and Harlem looks

very different. Some call it a renaissance, some call it gentrification.

JS:

The thing that I like about it is that although there are some drugs in

there it's not a drug movie because that was a small part about what was

going on in Harlem when I was there. I mean, you could certainly find

syringes in the playgrounds and stuff like that but it wasn't the dominant

factor. The dominant factor was that people were trying to get by and

they had jobs and the kids went to school in the morning. The part that

I like about [Brother] and I think is still current is that you

see people in all these different echelons. You see street people who

are sleeping outdoors, you see some fairly well-to-do people and then

you see a lot of people in the middle who are just trying to get by. I

think that it would have seemed the most anachronistic during the crack

plague. There was about a five or six year period when crack was like

the Spanish influenza of 1920. It just killed a lot of people in a very

short period of time. It's still around but the vestiges of it are a lot

smaller than they used to be so I think that actually what's happened

is that Harlem has kind of normalized since then.

CG: You

financed Brother yourself. How does it feel to make films without

anybody looking over your shoulder giving you unwanted input?

JS: I

don't have that much more [outside] input now. The experience was nice because it

was a four week film. The next movie I'm going to shoot will also be about

four weeks and about a million dollars, which is probably about what three-

or four-hundred thousand was when we made Brother and you get a

certain amount of energy from that. On that one we were working with a lot

of crew people who were very new. A lot of people were working about one

notch up from whatever level they had worked before and really that also

gave us a lot of great energy. Ernest Dickerson, that was the first 35 mm

movie that he shot and for a lot of the other people it was their first

time as a first instead of a second. And also Harlem gave us a lot of energy.

We didn't depopulate it and then repopulate it with our extras. We basically

would have one or two of our extras to mix in with all the people who were

just there on 125th street doing their stuff. And they had things to do

so we weren't that interesting to them.

CG: I'm guessing

your control over the film didn't extend to distribution. The back of the

video box describes the film as "non-stop action" and "hard

hitting comedy," which are both pretty ridiculous descriptions.

JS: Yeah,

we don't have any control over that. We kind of sell it to somebody and

just say, "You can't cut it." That's about all you get to do.

|

All of John Sayles'

films tackle tough, real subjects, and every one deserves to be seen. The retrospective

runs through the middle of August all around the country. Check out the

official site for specific show dates and times near you. For those in the

New York area, Sayles will speak at the 7:15pm show on Thursday, June 13

at the Jacob Burns Film

Center (914-747-5555). Sayles will also speak at Chicago's Gene Siskel Film Center on Thursday, June 20 at 8:15 p.m. Make sure you don't miss it and watch this space

for updates on the DVD release.

Links:

John Sayles Retrospective

(Info and Showdates)

Some of the theaters taking part in the retrospective (see above link for complete

list):

Jacob Burns Film Center

(Pleasantville, NY)

Brooklyn Academy of Music (Brooklyn,

NY)

Coolidge Corner (Los Angeles,

CA)

Starz

Film Center (Denver, CO)

Cinestudio (Hartford, CT)

Magnolia

Theater (Dallas, TX)

Varsity

Theater (Seattle, WA)

Gene Siskel

Film Center (Chicago, IL)

Click

here to submit a film event or to contact CINEMA GOTHAM

|