| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

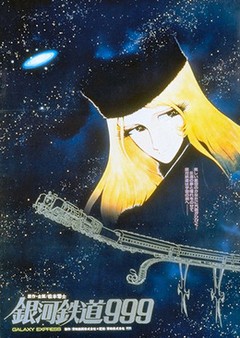

Galaxy Express 999

Despite specializing in Japanese cinema and having lived here since 2003, I'm not especially enamored of this country's anime. Hayao Miyazaki and his Studio Ghibli have rightly cultivated a worldwide following but for me much of the rest of it, such as Katsuhiro Otomo's landmark Akira (1988), I find visually stupendous but also hopelessly confusing. Such films tend to leave me cold if impressed. Partly that's because unlike American animated films, Japanese anime often targets hardcore fans already familiar with the often epic, 1,000-plus-page manga (Japanese comic book) from which they're based. There's an expectation that the viewer is already fully immersed in its endless universe and hundreds if not thousands of characters (Pokémon, Anpanman) and nearly as much symbiotic merchandising.

Galaxy Express 999 (Ginga tetsudō 999, 1979) is another big landmark film in the history of Japanese anime. Preceded by an award-winning manga and television series, the movie was a colossal hit, one of the year's top-grossing movies. And while the film version apparently boils down a complex story to a little over two hours, I was surprised to find myself almost hypnotically sucked in. Like other landmark anime it resembles Western-style animation almost not at all, and while less fluid than Disney's famous animated features it's consistently striking and wildly imaginative - and also more adult and intellectually challenging.

A Discotek Media/Eastern Star release, the 16:9 enhanced widescreen DVD is superb with an especially outstanding stereo surround mix of the Japanese audio (an English-dubbed version is included, but you'll want to avoid that). Extras are limited but interesting.

Its an odyssey set in a distopian future, tracing the adventures of 12-year-old Tetsuro Hoshino (voiced by Masako Nozawa in the Japanese version), a street urchin. After his beloved mother is murdered and made a hunter's trophy by Count Mecha (Hidekatsu Shibata), an immortal human with mostly mechanical parts, Tetsuro vows to kill him someday and avenge her murder.

Believing his only chance to defeat Count Mecha is by becoming a nearly indestructible mechanical creature himself, Tetsuro tries to board the Galaxy Express 999, a space train that makes yearly trips from Earth to Andromeda, where wealthy humans trade-in their tired old bodies for new if mechanical ones.

He meets a rail-thin, pouty-faced young woman named Maetel (Masako Ikeda) who, except for her long blonde hair, strongly resembles Tetsuro's mother. (Distressingly for this viewer, she also bears a striking resemblance to Paris Hilton.) She offers him use of her rail pass provided he accompanies her all the way to Andromeda as her traveling companion. He readily agrees. Along the way the Galaxy Express 999 has layovers on Saturn's moon Titan; the frozen Pluto; a planet beyond the solar system called Melder; and finally the Mecha planet. Gradually, Tetsuro realizes that the immortals have mixed emotions about their indestructible bodies and this ends up taking the story in unexpected directions during its final third.

The movie condenses and makes some changes to Leiji Matsumoto's original 1977 manga, as well as the concurrently airing animated television series, first broadcast on Fuji Television from 1978-1981. The movie version was directed by Rintaro* (born Shigeyuki Hayashi), with Kon Ichikawa (The Burmese Harp, Tokyo Olympiad) credited as a kind of supervising director or directorial adviser, though it's not entirely clear what his function would have been. Rintaro's credits include the acclaimed Metropolis (2001), based on both the Osamu Tezuka manga and Fritz Lang's silent film classic.

In any case, the very good screenplay poses myriad questions about what it means to be human and mortal versus mostly mechanical yet immortal and virtually indestructible. Claire (Yoko Asagami), for instance, is a dining car waitress aboard the Galaxy Express, whose artificial body is made entirely of crystal glass and thus she's transparent. Tetsuro admires her beauty, but she is saddened by the way light simply passes through her and by her literal lack of warmth. Forced into this body by a vain mother - a reference perhaps to the selling of young girls to geisha houses in the Edo Period - Claire is saving her money, hoping to buy back her mortal body, which is being held in storage back on Pluto.

On Pluto, Tetsuro visits a graveyard where the frozen bodies of those who transferred their souls into mechanical bodies are buried under the ice - bodies highly visible from the surface, like a mass grave of glass coffins.

Visually, the picture is extremely interesting, with designs reflecting its distopian future society where the wealthy move about in cavernous ballrooms and train station lobbies generally either ultra-futuristic or neo-Renaissance, typically ornately European rather than Asian in terms of design. (Amusingly, a few singularly Japanese attitudes crop up. When Maetel treats Tetsuro to a fancy meal aboard the Galaxy Express, it's what in 1979 was considered the ultimate in fine dining: beefsteak, corn soup, and Japanese rice.)

Beyond the more familiar become-immortal-and-risk-losing-your-humanity theme, Galaxy Express 999** is surprisingly political in content, with the über-rich living like Kim Jong-Il on spacious but empty streets resembling Pyongyang. They casually hunt down the poor for sport, stuffing and displaying them on walls as trophies. Maetel herself is dressed like a pre-Revolution Russian countess.

Certain concepts alien to western viewers, like an old-fashioned locomotive speeding through the galaxy, are logical and even almost scientifically plausible as explained in the film. Though things get a little confused during the slam-bang climax, where the budgetary limitations also show a little, I was pretty much taken with Galaxy Express 999 from beginning to end.

Video & Audio

Presented in 16:9 enhanced widescreen, the 1.85:1 Galaxy Express 999 looks practically perfect, with excellent sharpness, color and contrast. The region 1 encoded disc has knockout stereophonic surround audio for the Japanese language tracks (with yellow English subtitles), audio much superior to the flatter, English-dubbed version.

Extra Features.

Supplements are limited to a modest still gallery (with no behind-the-scenes shots, sadly) and two interesting Japanese trailers, also enhanced and subtitled, one for this and the other for Adieu, Galaxy Express 999, the 1981 sequel.

Parting Thoughts

A must not only for Japanese anime fans but fans of feature animation generally. This is a landmark work and one certain to appeal to a broader audience that normally steers clear of this sort of thing. The excellent transfer also makes this a pleasure to watch. A DVD Talk Collector Series title.

* According to Wikipedia, "His pseudonym is sometimes miswritten as Rin Taro or Taro Rin." However, in the movie, onscreen, the director's name is listed as "rin ・ taro," not "rintaro." However, nearly all Japanese websites list the name without the "・" - in other words, "Rintaro."

** In this instance, the Japanese say "three-nine" ("suri nain") rather than the Japanese words for "nine - nine - nine" or "nine hundred ninety-nine."

Stuart Galbraith IV's audio commentary for AnimEigo's Tora-san, a DVD boxed set, is on sale now.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||