| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection

Bringing many of Hitchcock's films to Blu-ray for the first time, Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection offers, in one box, a veritable galaxy of brilliant work by the man who, when all is said and done, can creditably be considered the greatest movie director ever, at least in the English-speaking world. In this galaxy there are the Plutos, the curious outliers begging for further exploration -- Saboteur (1942), The Trouble with Harry (1954), Torn Curtain (1966), and Topaz (1969). Here, too, are the magnificent, multilayered Saturns and Jupiters, replete with rings and moons of ceaselessly inventive, bravura filmmaking -- Rope (1948), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), Psycho (1960), and The Birds (1962). There's also a touch of Venus, with North by Northwest (1959) and Marnie (1964) mixing matters of the heart, mind, and hormones into inimitably strong sexual-romantic cocktails. And then there's the brilliant, blazing star around which all the others orbit, comprised of the three single greatest contributions the master made to the filmography of the ages, perfect films all: Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Rear Window (1954), and, glory of glories, Vertigo (1958). Finally, there are the pale moons -- Frenzy (1972) and Family Plot (1976) -- that, after that sun sets, keep on luminously reflecting its light. Having so categorized the wealth of cinematic wonders spilling over from this deceptively compact package, we'll work our way through the set not chronologically, but in a direction from more peripheral to absolutely central (not just in Hitchcock's oeuvre, but in anyone's experience of the movies), always keeping in mind that it's space and time limitations that necessitate these handy thumbnails, and even the least of these films could inspire several in-depth essays....

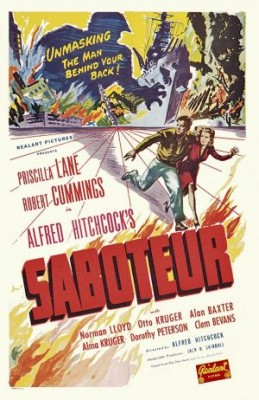

Hitchock was never really a topical or explicitly political filmmaker, which may have something to do with the slightly more rote, somewhat less "purely Hitchcock" feel of Saboteur, Torn Curtain, and Topaz. Saboteur is probably the best of this grouping, with its tension-filled, reluctant romance between stars Robert Cummings and Priscilla Lane, fueled by mistaken identity and constant jeopardy after an aircraft-manufacturing plant is bombed by enemy agents during WWII, recalling Hitchcock's earlier The 39 Steps. Similarly, Torn Curtain's saving grace is the disorientation and divided loyalty that Julie Andrews experiences when she discovers that her fiance, Paul Newman (the two make a surprisingly effective, chemistry-laden onscreen couple) means to defect to the Soviet/East German side in the thick of the Cold War. Topaz, with its cast of international stars (e.g., Contempt's Michel Piccoli), is the most dated of the bunch, in a way that places Cold War machinations front and center, sapping its energy somewhat and making it feel heavy, weighted down, unconvincing; its source is a humorless potboiler novel by Leon Uris, and it betrays those origins too often to come off completely (even Hitchcock later declared that what he meant to be an intriguing experiment in color-coding, with the plot coming secondary, didn't ultimately work -- though it must be said that the colors, as rendered by cinematographer Jack Hildyard (Summertime, Modesty Blaise) are delectable). Its overstuffed plot about personal and political loyalties clashing amid CIA/Cuba/KGB intrigues, along with its indecisive ending(s) (various conclusions for various versions, all included here for your perusal) are still worth tolerating, however; Hitchcock never made a picture that lacked his impressive, assuredly choreographing visual sensibility, and when you see Topaz's numerous, elegantly dynamized shots and montage, the most memorable example of which is a cut to an overhead shot as a woman (Karin Dor) collapses after being shot out of her lover's tender mercy, her gown "pooling" beneath her like blood against the stark black and white checkered floor. Similarly strong moments -- the thrilling climax on the Statue of Liberty or the sinisterly quiet, nonchalant revelation that a friendly grandfather is dangerous in Saboteur; Torn Curtain's hair-raising, not-for-the-claustrophobic final escape from a ballets russes performance -- punctuate, and go a long way toward redeeming, the other two as well, with Hitchcock's unflagging visual precision and fluidity taking up much of the excess slack elsewhere throughout these (relatively) weaker entries. As for The Trouble with Harry, the closest to a flat-out lark in the box, it's "minor" and mild-mannered by design, with an ensemble of actors (including Shirley MacLaine, in her big-screen debut, and Hitch's later Topaz star, John Forsythe) playing out, against a magnificently shot (by Robert Burks, who shot many of the films included in this collection), autumnal New England backdrop, a snowball of misunderstandings in which multiple characters feel culpable for the suspected murder of a man they didn't kill but whom nobody really liked. It's a comedy in the Shakespearean sense, culminating in not one but two happy romantic pairings, the principal of which is that between the spunky MacLaine and the Thoreau-ish painter Forsythe (a sort of comic counterpart to Rock Hudson's nonconformist in the contemporaneous All That Heaven Allows).

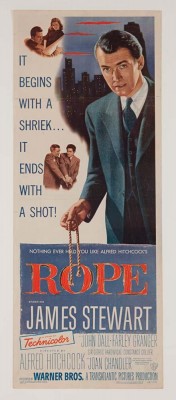

Jimmy Stewart began his long and very fruitful collaboration with Hitchcock on Rope, an oddly (and, most often, very successfully) experimental work that plays out in real time, over the course of a dinner party with a murderous underlying secret, with almost no cuts, the camera following the characters from framing to framing and room to room without skipping a beat, in a transfixing dance as Stewart, a college professor who blithely spouts quasi-Nietzchean, beyond-good-and-evil platitudes, slowly but surely realizes that the two of his former students (John Dall and Farley Granger) hosting the gathering have taken him at his word, thrill-killing a third ex-pupil and hiding the corpse right under the noses of the guests. With its proudly matte-painted "New York skyline" glowing through evening, dusk, and into nightfall outside the apartment-set windows, Rope may be the purest example of Hitchcock's career-long embrace of artifice as an aesthetic strategy, and is something beautiful to behold. No less so are the use of rear projection and colorfully well-appointed sets and costumes used to create an exotic, threatening world around Stewart's midwestern doctor and his restless, former-famous-singer wife Doris Day in The Man Who Knew Too Much, which rightly keeps the Cold War machinations way in the background, focusing instead on the rude awakening experienced by the blissfully ignorant, surprisingly resourceful American tourists' horror at finding themselves submerged in it, forced into a nightmarish quest to find their kidnapped little boy, who's being held to oblige the doctor's silence vis-à-vis some incriminating words whispered to him by a dying man.

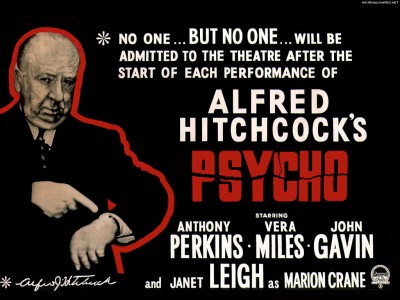

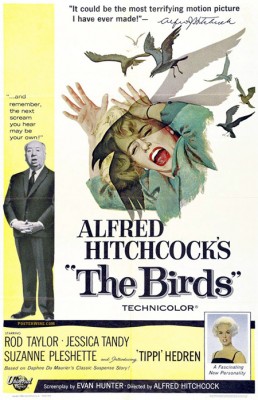

The Birds marks another performer's debut under Hitchcock's auspices, this one of a more alluringly feminine sort: Cool blonde Tippi Hedren, Hitchcock's find and protégé, is a frankly sexy, confident, aimless young woman from a wealthy family who's caught between unruliness and civilized order, both within herself and, more frighteningly and violently, in the exterior world, where the birds of the little Northern California coastal town -- where Hedren is staying to pursue a hunky man (Rod Taylor) a bit too under his mother's (Jessica Tandy) thumb -- have mysteriously banded together and mounted increasingly savage, aggressive attacks on the townspeople. Here, once again, Hitchcock employs artifice -- those birds, who sometimes swarm in Jackson Pollock-like abstract squiggles across the screen; the use of rear projection and hybrid studio/location shooting highlighting the tension between realism and frank illusion, nature and civilization; that final, haunting, painting-like shot in which the survivors of the birds' attacks head off toward what looks to be a matte-painting horizon lit by shafts of heavenly but clearly fake light -- to create a sinister storybook about how illusory are our anthropocentric assumptions about the human animal's relation to the natural world it comes from and lives in. And then there's the much more documentary-like Psycho, its deceptive black-and-white appearance of realism sliced into something sleek, foreboding, and inevitable in the cutting room, propelled swiftly along toward doom by perhaps the most instantly recognizable of Bernard Herrmann's many Hitchcock scores. The film's notorious "shower sequence," storyboarded precisely and painstakingly edited to create a flurry of cuts between the shots to match the one depicted within them, works so effectively on so many levels at once, from the most viscerally repulsed to the most admiringly cerebral, it's no wonder that it's the single sequence most commonly associated with Hitchcock in the popular imagination. (No less ingeniously innovative, if more subtly so, is the film's gloriously perverse structure, in which the story we think we're watching gets derailed after the first third and becomes something quite different in the aftermath -- a structure whose jarring legacy has lived on in films that pay it homage, from Dressed to Kill to Full Metal Jacket to Storytelling).

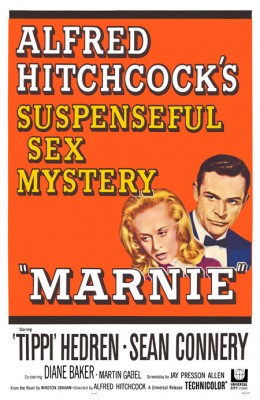

Hedren's next, final role for her discoverer was even better: the psychologically scarred thief of Marnie's title. Marnie is a kindred spirit of sorts to Cary Grant's frivolous, overgrown playboy in North by Northwest; despite their apparent disparateness, the films that give these two children in adult bodies are both equally fine and strangely complementary. They're both twisty-turny romances that depict the processes of growing into actual maturity and falling into actual love as tortuous strivings, whether it's Grant's obsessive desire for Eva Marie Saint and Eva Marie Saint alone leading him, another in Hitchcock's large gallery of "ordinary," glibly indolent and overconfident men whipped into shape through the interventions of coincidence and mistaken identity, into situations where he risks getting attacked by a crop-dusting plane or falling from the face of Mt. Rushmore. The unbearably sexy but implicitly frigid Marnie, for her part, must face up to a horrific repressed memory and the domineering mother (there's quite a long line of those in Hitchcock, too) for whom she's repressing it before she can attain her desire to melt at last under the ruggedly masculine hand of Sean Connery. North by Northwest, a superlative and exhilarating thriller, was a hit and is a well-established Hitchcock classic; it's too bad the different but equally excellent Marnie's box-office failure and lukewarm reception seemed to end the director's collaboration with Hedren and his melodramatic impulse. To at least the same extent that the swooningly emotional Rebecca decades earlier, Marnie, with its emergency-red flashbacks and women's-picture preoccupation with feminine iconography, ritual, and identity, suggests that Hitchcock could have been a compatriot of Douglas Sirk and Fassbinder.

Of course Marnie, great as she is, is only younger sister to Kim Novak in Vertigo, with its even more powerful exploration of the same themes. But when it comes to Vertigo, that's only a part of it: It's almost too much, the way Hitchcock reaches with this film the furthest possible heights of everything he's about, creating a world-class masterpiece (one that, with much ado, recently beat out Citizen Kane as Greatest Film Ever Made in Sight & Sound's comprehensive critic's poll). The upstanding, upright, apparently well-adjusted regular guy (Jimmy Stewart) sucked by coincidence and slippery, elusive identity into something he doesn't understand, can't control, and can't get out of? Check. A passionate, obsessive love hopelessly complicated by submerged pasts, inscrutable desires, and murky motivations? Check. The persistent, uncannily dream-like feeling of something important and very dangerous just around the corner, just out of sight? Check. The vertiginous chasm that opens up when the beautifully artificial and the sobering, despondently real, set on a collision course, finally collide, shattering apart the seemingly rational, ordinary, and predictable veneer of life? Double check. No wonder Vertigo wasn't a hit upon its release, or that its stature grows with every passing year; it's Hitchcock's most serious film in every sense, a tensely anxiety-ridden modernist masterwork to rival Antonioni's L'avventura or Bergman's Persona with its deeply troubling look at the irresoluble problems of alienation, a permeating and amorphous sense of loss, and the instability, deceptiveness, and warped projections of identity. Very nearly as breathtaking and disquieting is Raymond Burr's murderous husband in Rear Window, who's an actor in a panoramic drama -- love! pain! sex! suspense! -- that seems to play out just for the diversion of wheelchair-bound photographer Jimmy Stewart, who can observe everyone through his binoculars and telescope from his comfortable, shadowed observation perch overlooking the courtyard of his building. His and on-again, off-again fiancee Grace Kelly's ongoing date night at this ever more enthralling "movie" turns on them, though; in yet another testament to Hitchcock's taut visual and conceptual genius, few moments in the movies are as terrifying as when the gazed-upon murder suspect gazes right back at Stewart (and, by extension, us), then shows up in his apartment, violating the voyeur's privileged space, demanding menacingly, "What do you want from me?" This is infinitely more disconcerting because we, from our own invisible vantage point, are doing to Stewart and Kelly and everyone else what Stewart is doing to Burr and his other neighbors, and it would be terrifying to be confronted by the those we observe with the sadism always implicit in our detached looking -- for what? Titillation? Escape? Catharsis? Release of violent impulse? What do we want from them?

Shadow of a Doubt, too, pulls back a veil to reveal something deeply disturbing behind a comfortable, complacent illusion, but not the one Teresa Wright's wide-eyed young protagonist, "Little Charlie," thinks. She's stifling in her family's Californian small-town health and contentment, and she longs for her dashing, footloose Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) to come visit them from back East. But the worldly cosmopolitanism she projects onto Uncle Charlie is in reality an enraged, soul-sick nihilism, and he's only returning to his family's bosom to evade the consequences of some ghastly, cruel crimes he's committed. Like Stewart in Vertigo and Rear Window, the allure of something that looks pretty and seems exciting will reveal itself as what it really is to Little Charlie only after it may be too late, and even if she can extricate herself from the abyss she's opened up, she won't be left unmarked. Shadow of a Doubt is Hitchcock's first perfect film; from its recurrent, progressively more disturbing image of couples elegantly ballroom-dancing to its tension-building use of subjective point-of-view shots to the wonderful rhyming dollies-in that introduce us first to Uncle Charlie, then to Little Charlie, as each daydreams or plots while lying in bed with their arms folded behind their head, it persistently takes stylistic chances that clearly give its maker a great thrill, and it pulls them all off with an astonishing panache, never once making a misstep or ringing a false note.

And then there's the afterglow. Hitchcock ended his career in the '70s with two films that rather neatly and insouciantly sum up much of what he accomplished over the preceding decades: Frenzy allows him to go back to his native England (where he began his career and made many a fine film before emigrating to Hollywood in 1940 to make Rebecca), bringing along the suspense and horror tricks he'd honed across the Atlantic, to tell the story of the grisly "necktie murderer"/rapist (Barry Foster) and the innocent man (Jon Finch) who, naturally, after his ex-wife falls victim, is wrongly suspected of the crimes. Hitchcock has good, sardonic fun with Englishness and class culture while at the same time serving up some of his most chilling, terrifying images: The rapes/murders are not depicted very graphically, but they seem to be, aestheticized as they are in an equal but opposite way to Peckinpah's slo-mo sensuousness, with smooth, cerebral rigor in framing and editing that are all the more unsettling for their sheer formal beauty. Then, unexpectedly but wonderfully, Hitch's last cinematic gasp took him out as a filmmaker with a wink and a smile. Family Plot concerns a pair of hapless, loveable San Franciscan con artists (Barbara Harris and Bruce Dern) lured by reward money into a thick, dangerous plot that pits them unwittingly against a much more competent and evil criminal pair (William Devane and Karen Black). There is something liberated and lively, even "loose" (though never less than technically and aesthetically inspired -- check out that magnificently made chase scene) that suggests, bittersweetly, that Hitchcock would have had many more in him, and who knows where he would've gone. It's marvelous the way Hitchcock concludes the film on Harris smiling and winking at us: for her, a fake psychic who discovers that her con/illusion actually is real, the trajectory has by complete accident been the opposite of what we expect from Hitchcock; the film keeps the great man in his best thematic territory (illusion/delusion vs. reality) and modes (suspense, attempted murder, mordant humor) while well earning that sparkling, apt, and touching happy ending to both one last fine film and to an incomparably illustrious run of filmmaking creativity to which, despite being many decades long, any end was going to seem much too soon.

There are, of course, other Hitchcock galaxies, too, even ones concurrent with the 15 works collected in The Masterpiece Collection; The Wrong Man, for example, made (between The Man Who Knew Too Much and Vertigo) for Warners and thus outside the Universal provenance of this box set, is at least one other film without which any collection of Hitchcock masterpieces cannot be considered definitive. But this box does compile an exceedingly generous chunk of the master's filmography with titles that are never less than visually captivating, and it includes his three very greatest pictures -- movies without which any home-video library has to be considered incomplete. Over the numerous enraptured viewings and re-viewings they so appealingly invite, they'll remind you again and again, in many aesthetically, technically, and narratively powerful and brilliant ways, that Hitchcock's body of work was and remains an eminently achieved, influential fountainhead from which cinematic inspiration, inventiveness, and accomplishment seemed to flow from some pure, bottomless source.

THE BLU-RAY DISCS:

Each disc presents its film in an AVC/MPEG4, 1080p transfer at the original theatrical aspect ratio (1.33:1 from Saboteur through Rope; 1.66:1 for Rear Window; and 1.85:1 for everything else) except for North by Northwest, which was matted every which way in its theatrical release and remains justifiably re-matted at 1.78:1 here, as it was on the previous 50th anniversary Blu-ray release.

The picture quality for this long-awaited Blu-ray collection encompassing some of Hitchcock's greatest films has been the subject of some controversy and contention, with an outcry from a qualified source actually going some way toward compelling Universal to delay its release to ostensibly correct some of the deficiencies. Not having seen the original, apparently objectionable check-discs, however, I can only judge by what my own eyes see in the retail product, and it looks fairly good overall. But there's a caveat in that "overall": While everything from Shadow of a Doubt through Psycho would, with their vividness of color, sharpness of image, and healthy levels of celluloid-grain texture, count as four-star visual presentations (the only real deficiency being a consistent but extremely slight edge enhancement, unnoticeable unless you're looking for it, with other glitches such as brief, rare color temperature fluctuations or small white "pops" occasionally evident in The Man Who Knew Too Much owing to the extreme poorness of some of the films' original source materials, which have been extensively restored to much, much better condition, despite any small remaining imperfections), the criticisms that were leveled about some of the overuse of digital noise reduction (DNR) in several of the films (particularly Frenzy), some mixed image quality on The Birds leading sometimes to sharp differences in image texture/quality from shot to shot, and some over-softness of the image on Marnie and Torn Curtain appear not to have been mitigated. That means that the picture quality for the set averages out to something less than excellent, and while every disc is watchable, we're left waiting for the definitively cleaned-up Blu-ray editions of some of Hitch's neglected, fascinating, brilliant '60s and '70s work. The **** to ****1/2 visual treatment of some of the films is countervailed by some **1/2 or even ** picture quality on others, for an average of a respectable but less than ideal ***.

Every disc in Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection provides its film's soundtrack in conscientiously restored and transferred DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 mono (save for North by Northwest, which offers Dolby TrueHd or DTS 5.1 options). Across the board, I found no deficiencies to report, with Bernard Herrmann's vital, unforgettable scores resonating wonderfully well, all dialogue full and even, and those piercing bird sounds ringing out loud and clear, with no distortion or imbalance anywhere. Vertigo's and Psycho's 5.1 soundtracks are for hardcore audiophiles who are casual movie buffs only; cinephiles will want the very nicely-done, original mono soundtracks (it is a shame that North by Northwest doesn't include that option, but its sound quality is still very fine). Most of the films have a French-dubbed soundtrack option as well, some offer Spanish dubbed-over sound, and all titles have English SDH subtitles as well as subs in various other languages.

Each disc in Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection (excluding North by Northwest and Psycho, both of which replicate their recent standalone Blu-ray releases) contains at least the same extras as its DVD counterpart in the 2005 Masterpiece Collection, with the exception of the previously included onscreen-text production notes, which are dispensed with on the Blu-rays. These are listed below, disc by disc, with additional extras for these editions as indicated:

--Saboteur has "Saboteur: A Closer Look" (35 min., 2000), a mini-documentary, with Pat Hitchcock O'Connell (Hitchcock's daughter, living representative of his estate, and omnipresent on all documentary extras); actor Norman Lloyd, who played the saboteur of the title; and associate art director Robert Boyle discussing the director and their recollections/impressions of the film, along with the film's theatrical trailer and a slideshow of promotional materials and stills.

--Shadow of a Doubt has "Beyond Doubt: The Making of Hitchcock's Favorite Film," (35 min., 2000), which includes interviews regarding the film with Pat Hitchcock O'Connell and Robert Boyle; with two of the film's stars, Theresa Wright and Hume Cronyn; and with director Peter Bogdanovich. Also included are the theatrical trailer and slideshows of production drawings and production photographs.

--Rope includes "Rope Unleashed" (32 min.), with Pat Hitchcock, actor Farley Granger, Hume Cronyn (who wrote the script treatment with Hitchcock); the film's devilishly clever theatrical trailer (which depicts the film's corpse before the dinner party, in his living state); and a slideshow of production photographs also featuring images of promotional materials.

--Rear Window has "Rear Window Ethics: An Original Documentary" (55 min., 2000), featuring interviews with Pat Hitchcock, various Paramount employees who worked on the picture, various crew members, score composer Franz Waxman's son John, film critic/scholar Robin Wood, L.A. Confidential director Curtis Hanson, audio excerpts from a long-ago Bogdanovich interview with Hitchcock, and important details on the film's very challenging restoration by film restorers James C. Katz and Robert A. Harris; "A Conversation with Screenwriter John Michael Hayes" in which Hayes recalls meeting Hitchcock and their development of the first of several Hayes/Hitch screenplay collaborations on Rear Window; the film's theatrical trailer and re-release trailer (the latter narrated by Jimmy Stewart); and a slideshow of production photographs including promotional materials and stills from the film. Supplements not previously included on the Masterpiece Edition DVD include: Two documentaries, "Pure Cinema: Through the Eyes of Hitchcock" (25 min.) and "Breaking Barriers: The Sound of Hitchcock" (23 min.), which explore Hitchcock's genius and, in particular, his ingenious use of sound with copious examples and interview clips with filmmakers Martin Scorsese, Guillermo del Toro, John Carpenter, and William Friedkin; editors Bill Pankow and Craig McKay along with large handful of other Hollywood technicians who rightly admire Hitchcock's technical prowess; and critic David Sterritt. (This is the first of a group of documentaries encompassing the same interviews spread out over the set's remaining discs.) Also included is "Hitchcock/Truffaut on Rear Window" (16 min.), the first in a series of the relevant excerpts, spread out over the remaining discs, from François Truffaut's famous, very long film-by-film 1962 interview with Hitchcock (presented as audio accompanied by clips from the film); "Masters of Cinema: Alfred Hitchcock," a fascinating half-hour in-studio interview with the master himself from what looks to be an episode of a British television series broadcast sometime near the end of Hitchcock's career; and, finally, Hitchcock's Rear Window: The Well-Made Film author John Fawell's feature-length audio commentary from a 2008 DVD release of the film.

--The Trouble with Harry includes "The Trouble with Harry Isn't Over" (32 min., 2000), a documentary once again featuring Pat Hitchcock O'Connell, screenwriter John Michael Hayes, actor John Forsythe, Bernard Herrmann biographer Steven C. Smith, and others; the by now standard, thoroughgoing slideshow-gallery of promotional material and stills from the film; and, disappointingly, the film's VHS release trailer in lieu of the theatrical trailer promised in the package's description of extras.

--The Man Who Knew Too Much has "The Making of The Man Who Knew Too Much" (34 min., 2000), again with Hitchcock O'Connell, Hayes, along with associate producer Herbert Coleman and production designer Henry Bumstead; the film's original theatrical trailer (with Stewart addressing us, the audience, to describe the picture for us) and re-release trailer narrated by Jimmy Stewart; and the standard slideshow-gallery of promotional materials and stills.

--Vertigo includes "Obsessed with Vertigo: New Life for Hitchcock's Masterpiece," a half-hour program made in 1997 for American Movie Classics, featuring Hitchcock O'Connell, Martin Scorsese, and restorers Robert A. Harris and James C. Katz commenting on the film, with particularly valuable insights from Harris and Katz into restoring it (with before-and-after demonstrations); the film's foreign censorship ending (a two-minute sequence with Stewart returning to Bel Geddes -- thank goodness you've never seen the film ruined with this tacked-on, inappropriate happy ending, which Hitchcock shot under obligation and against his will); the film's original theatrical trailer and 1996 re-release trailer; "The Vertigo Archives," an even more extensive slideshow-gallery than included for the other films, with over 400 sketches, photos, and clips of promotional materials. Supplements not previously included on the Masterpiece Edition DVD include: Feature-length audio commentary with director William Friedkin (swapping out the previous Masterpiece Collection commentary by associate producer Herbert Coleman, though both, along with many of these additional supplements, are included on the two-disc special edition DVD of Vertigo from 2008); the Hitchcock/Truffaut interview excerpt centered on Vertigo; and the first two of the set's interspersed extras not exclusively related to the accompanying film, "Partners in Crime: Hitchcock's Collaborators," about an hour's worth of separate segments devoted, respectively, to title designer Saul Bass, costume designer Edith Head, score composer Bernard Herrmann, and Hitchcock's wife/behind-the-scenes collaborator, Alma Reville; and 100 Years of Universal: The Lew Wasserman Era," a seven-minute clip celebrating the storied Universal Studios head, under whom several of Hitchcock's late-career works were distributed.

--North by Northwest appears to be precisely the same Blu-ray previously released as the film's "50th Anniversary Edition," and includes: Feature-length audio commentary with screenwriter Ernest Lehman telling stories aplenty about how he and the master concocted the cross-country thriller; "Cary Grant: A Class Apart," a 90-minute documentary biography about Grant's life and career made for TCM in 2004, featuring interviews on the actor with critics Elvis Mitchell and David Denby; film historians Jeanine Basinger and James Harvey; directors George Cukor and Peter Bogdanovich ; North by Northwest costar Martin Landau; and intimates such as Barbara Grant (Mrs. Grant from 1981-1986), among others; "The Master's Touch: Hitchcock's Signature Style," an hourlong documentary drawn from the same interviews (with Curtis Hanson, John Carpenter, Scorsese, David Sterritt, etc., along with bounteous archival footage of Hitchcock and surprise guests like pop-culture critic Camille Paglia) as the "Pure Cinema" and "Breaking the Barrier" pieces on prior discs; "Destination Hitchcock: The Making of North by Northwest" (40 min., 2000), introduced by Eva Marie Saint and featuring interviews with Lehman, Hitchcock O'Connell, Martin Landau, and footage from the film's glamorous premiere; "North by Northwest: One for the Ages," again from the same "Pure Cinema" and "Breaking the Barrier" pieces, this time with Hanson, del Toro, Friedkin, and other filmmakers honing in on North by Northwest; a stills gallery/slideshow with 45 images, from candid behind-the-scenes snaps to promotional materials to footage of Eva Marie Saint from the 2000 making-of; three original trailers for the film, including a TV spot, the theatrical trailer, and Hitchcock's delicious "travel agency" promotional spot.

--Psycho, like North by Northwest, is basically the film's "50th anniversary edition": It includes "The Making of Psycho" (90 min., 1997), featuring archival footage of Hitchcock discussing and doing promotion for the film alongside interviews with Hitchcock O'Connell, Hitchcock's personal assistant Peggy Robertson, screenwriter Joseph Stefano, horror author/filmmaker Clive Barker crew members, and others; "Psycho Sound" (10 min.), an exploration of the creation of the 5.1 surround mix for digital home media; "In the Master's Shadow: Hitchcock's Legacy" (25 min.) is from the same interview sessions (with Scorsese, biographer Spoto, Sterritt, etc.), with discussions of the director's ongoing influence and specific examples from their work and others'; the Psycho-centered excerpt from the Hitchcock/Truffaut interview (15 min.); an eight-minute promotional featurette from the film's initial run, created by the studio as a "pressbook on film" to explain the special circumstances under which the feature needed to be shown; the two-and-a-half-minute shower scene in isolation, followed by Saul Bass's shower scene storyboards (in slideshow form); "the Psycho archives," a slideshow of film stills, quickly followed by separately selectable collections of posters and newspaper ads, lobby cards, behind-the-scenes photos, and production shots of the actors; the film's original theatrical trailer (with Hitchcock "escorting us" around the Bates hotel/house set) and several re-release trailers from a few years after the film's initial run (promising you "the version they didn't dare show on TV!"). The erudite feature-length audio commentary is by Stephen Rebello, author of Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho.

--The Birds has script pages and photos from a deleted scene in which the flirtation between Melanie and Mitch continues after the first in-home bird attack; script pages and sketches for an unshot original ending, "The Birds: Hitchcock's Monster Movie" (14 min.), including interviews with directors Ron Underwood (Tremors) and Joe Dante (Gremlins) alongside several horror and Hitchcock experts; "All About The Birds" (80 min., 1999) featuring interviews with Hitchcock O'Connell, screenwriter Evan Hunter, stars Tippi Hedren and Rod Taylor, Peter Bogdanovich, makeup artist Howard Smit, and others, about the making of the film; a storyboard sequence that breaks down, matching storyboards to still shots, the scene in which Melanie Daniels is attacked by the birds in the attic; Tippi Hedren's screen test (9 min.), several test shots (apparently for To Catch a Thief, not The Birds, with Hitchcock giving instructions from off-camera; the Hitchock/Truffaut interview (14 min.) excerpt centered on The Birds; "The Birds is Coming," a one-minute promotional "newsreel" for the film; "Suspense Story: The National Press Club Hears Hitchcock" another brief promotional "newsreel"; the slideshow-gallery of production photographs and promotional materials; the original theatrical trailer, five minutes with Hitchcock. Also included are non-Hitchcock-related Universal promotional supplements "100 Years of Universal: Restoring the Classics" (10 min.) and "100 Years of Universal: The Lot", the latter featuring numerous stars and filmmakers paying tribute to Universal's famous filmmaking facilities.

--Marnie includes "The Trouble with Marnie" (58 min., 1999), interviewing Hitchcock O'Connell, actors Tippi Hedrin and Louise Latham, screenwriters Jay Presson Allen (as well as Evan Hunter and Joseph Stefano), Bogdanovich, critic/scholar Robin Wood, and others about the making of the film and its meaning; "The Marnie Archives" with many stills and images of promotional materials for the film; and the original theatrical trailer with Hitchcock, on a huge camera crane, telling us about it and introducing a couple of scenes.

--Torn Curtain has "Torn Curtain Rising" (32 min., 2000), a narrated documentary simply but still informatively telling the story (without, unlike the other such extras in the box, any of the actors or participants, or even Pat Hitchcock O'Connell) of the film's making; 14 minutes of scenes scored by Bernard Herrmann before the composer was replaced by John Addison, effectively finishing his long-running collaboration with Hitchcock; a slideshow-gallery of production photos and promotional materials; and a fairly beat-up but original version of the theatrical trailer.

--Topaz includes three alternate endings to the film; "Topaz: An Appreciation", a half-hour discussion of the film by Leonard Maltin; a storyboard sequence that breaks down a single scene (just like its counterpart on The Birds) and the slideshow-gallery of production photos and promotional materials; and the film's jazzy original theatrical trailer.

--Frenzy has "The Story of Frenzy" (44 min., 2000), which includes interviews with Hitchcock O'Connell, Bogdanovich; actors Barry Foster, Jon Finch, and Anna Massey; screenwriter Anthony Shaffer; and lots of behind-the-scenes footage from the shoot, with an introduction by Laurent Bouzereau (director/producer of many of these supplements); the standard slideshow-gallery of production photos and promotional materials; and the original theatrical trailer famously featuring Hitchcock floating in the Thames.

--Family Plot includes "Plotting Family Plot" (48 min., 2000), with Hitchcock O'Neill, assistant director Howard Kazanjian, and actors Bruce Dern -- an alumni of Hitchcock's TV show -- Karen Black, and William Devane discussing the making of the film; storyboards breaking down the film's fantastic chase scene; the standard slideshow-gallery of production photos and promotional materials, and two theatrical trailers, each with Hitchcock drolly presiding over clips from the film.

--"The Master of Suspense," a 60-page booklet with entries (each of at least one page) on every film collected in the box, including release date, promotional images, and trivia; full-page entries on frequent Hitchcock collaborators Saul Bass, Edith Head, and Bernard Herrmann; and brief written introductions to Hitchcock's work, themes, and legend.

We usually don't make a special point of reviewing the packaging of a product here at DVDTalk, but in this case, it seems in order: Anyone who has the 2005 DVD version of The Masterpiece Collection will recall its fine packaging, consisting of a box covered in a velvet-like felt with a "door" that opens to reveal four smaller cases, each containing four DVDs, with holders to snap the discs securely into place in an overlap fashion. It would have been advisable to replicate that packaging here, but instead, there's a cleverly designed but not very practical or sturdy package which consists of a "book" that slides out of the cardboard outer box; this "book" in turn has hard covers and contains "pages" inside, each cardboard "page" acting as a sort of envelope that contains one of the Blu-ray discs. I generally prefer jewel box/snap-in type cases for digital media, not the slide-in, paper-sleeve kind we get here, as sliding the discs out and replacing them brings the delicate bottom surface into contact and friction with the paper (which, I should note, is in this case very smooth and glossy, not at all rough, so probably not directly abrading the surface), which to my mind puts the discs at much further risk for scratches/damage when taking them in and out. A further issue with the edition I received was what seemed to be a step missing in the manufacturing process: each "page" constitutes an envelope meant to seal in the disc when you slide it in, but whatever adhesive was used in the manufacture of the copy I received has sealed the three sides of the "envelopes" that should be closed to hold the discs in very poorly, allowing for the discs to slide around inside the "envelope" pages, putting them at substantial risk of sliding down, poking out the bottom of their envelope and becoming difficult to grab and pull out; or, worse, sliding even further out of the back of the "envelope" into the space that the outer book's spine creates when opened. Overall, assuming that copies sent for review were from early in the run, it seems possible that better quality assurance as the packaging comes off the line may remedy the issue, but even so, it would have been preferable to have the discs packaged in something with less focus on the pretty (and this is good-looking packaging, if nothing else) and more on the simple, sturdy, and durable.

The new Blu-ray release of Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection presents a bit of a conundrum for both the reviewer and the cinephilic consumer. The 15 films themselves are, it almost goes without saying, unimpeachable; Hitchcock is the rarely-matched gold standard of how a filmmaker can work within "the system," make movies that work for pretty much anyone as instantaneously gratifying entertainments, and create the most aesthetically and technically breathtaking, dazzling, rigorous, sometimes devastating works of art that you can spend a lifetime getting more and more out of. Whether the films collected here are "minor" Hitchcocks (Saboteur's WWII propaganda, Torn Curtains's and Topaz's Cold War semi-coasting); classics of suspense, psychological unease, and intoxicating, iconic use of the cinematic language (Rope, The Man Who Knew Too Much, Psycho); the unforgettable, unexpectedly hard-hitting philosophical/psychosexual forays of The Birds and Marnie; assured, accomplished works from the master's late-career second (third? fourth?) wind (Frenzy, Family Plot); or works near-unanimously counted among the truly greatest films ever made, anywhere (the piercingly deep dramatic and emotional layers of Shadow of a Doubt, the haunting and sublime contemplation of the movie-watcher's experience in Rear Window, and Vertigo, the superlative ultimate masterpiece), every one of these pictures deserves and demands to be seen multiple times, some of them for their enduring thrill and the finesse on display, a few as curios that even so retain some real allure, and several because they've marked you (or will mark you, if you have yet to see them) for life and stand with the greatest artistic achievements in any medium. This already overwhelming cornucopia of movie riches is rounded out even further with a vast smorgasbord of supplements that take you further into the making, meaning, and enduring value of each of the films, from multiple historical, critical, technical, and biographical perspectives. Content-wise, then, Alfred Hitchcock: The Masterpiece Collection is an easy call: It unhesitatingly and unequivocally merits our highest stamp of approval, DVD Talk Collector Series.

Unfortunately, the technical dimension does put on the brakes, demanding some serious pause before recommending the set without reservation, for problems that extend well beyond the not very well-advised packaging (which, in the condition in which I saw it, was fairly shoddy on practical terms, but not a deal-breaker). The more salient issue is that, over the course of the films, what starts off as a very strong showing, picture quality-wise, begins to peter out just a little past the halfway point. One certainly feels that a higher standard should have been maintained from The Birds on, when the films begin to suffer alternately from too little and/or misdirected attention in the authoring (the fuzzy softness, lack of clarity and other indications of sloppiness on some of the films) or too much manipulation (the flattening-out overuse of digital noise reduction on others). The quandary is whether to spring for the box set, which does contain very good Blu-ray editions (many of them on Blu for the first time) of Hitch's most top-notch, famous, and acclaimed works, and hope for the "opportunity" to double-dip later, when ameliorated versions of a great film like Marnie and neglected accomplishments like Family Plot not quite given their due here will, one hopes, be made available; or, on the other hand, to hold out for possible single-title releases of the well-done Blus in the set (everything from Saboteur through Psycho) and take the same course with the remaining titles, waiting to see, on a case-by-case basis, whether their picture-quality problems have been solved. Given that nine out of 15 are excellent; that the remaining six, while problematic and in need of improvement to varying degrees, aren't actually deficient enough to be unwatchable; and that nine times the usual $23 or $30-each asking price for standalone Blu-rays would mean that buying only the nine above-par individual titles once they're available at some later point would still set you back more than the box containing all 15, our difference-splitting verdict for the essential, sometimes frustratingly technically flawed Masterpiece Collection is Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||