| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

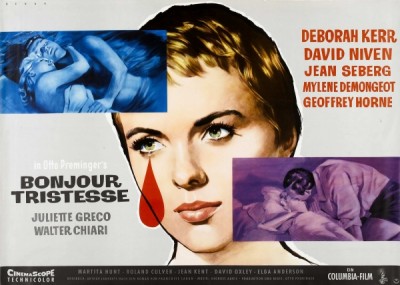

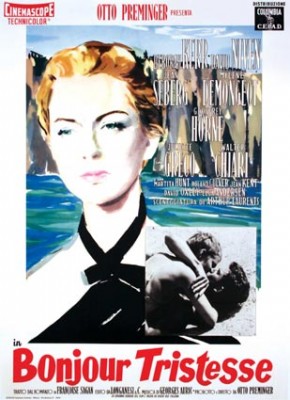

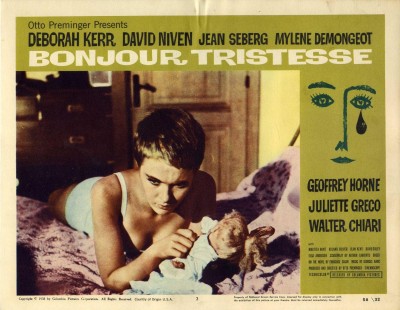

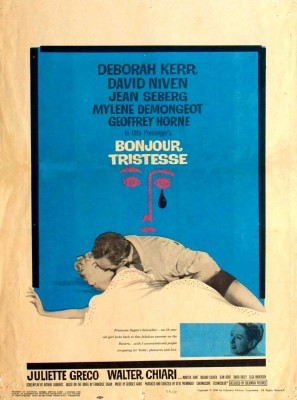

Bonjour Tristesse

Françoise Sagan's 1954 novel Bonjour Tristesse, published when she was only 18, is a bit like a French Catcher in the Rye: Its story, style, and characters are very different from Holden Caulfield and his "crummy" life, but it expresses a similar sort of teenaged confusion, longing, and disaffection -- a tender heart hidden behind a brave front -- and it left the same permanent mark on its culture as representative of adolescent defiance, skepticism, and melancholy. When director Otto Preminger (Laura, Anatomy of a Murder) decided to make a film version, he added an extra dimension of rebellion by casting his protégée, American actress Jean Seberg, as Cécile, the 17-year-old girl who discovers her heart, and those of the people closest to her, aren't as indestructible as she thought, despite the shell of high-rolling affluence that seems to surround them. Seberg had been Preminger's star, handpicked from a nationwide casting call, for 1957's Saint Joan, in which the young Iowan Seberg played Joan of Arc. That picture was a notorious flop, and Preminger's trenchant decision to continue with his ill-fated choice of female star on his very next film must have seemed perversely, self-destructively willful at the time. But we should be glad he did, and not just because Seberg would thereby catch the eye of a young Parisian film critic named Jean-Luc Godard, who was so taken with her screen presence that he would build his debut feature, Breathless around her. If Seberg had seemed miscast to some as the famously unequivocal Saint Joan, she's wonderful as the confused Cécile, a well-off daddy's girl, uncertain of exactly who she is, who's going through the pangs of first love and the fear of losing her father/best friend to remarriage. Under Preminger's direction, and surrounded by more seasoned, distinguished performers, Seberg shines from the screen the way the Mediterranean sun does on the French Riviera villa where most of this tragically romantic movie takes place.

Foremost among those experienced costars are David Niven (Powell & Pressburger's A Matter of Life and Death) as Cécile's father, Raymond, an affable, idle-rich womanizer who's sincere about only two things: his perpetually field-playing insincerity in matters of love and sex, and his complete, utterly indulgent adoration of his Cécile. Niven's fellow Powell & Pressburger alumni, Deborah Kerr (Black Narcissus, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp) plays Anne, the fashion designer who, despite her better judgment, is in love with Raymond and accepts his marriage proposal; Anne is the unwelcome breeze of pragmatic reality invading the little bubble of Continental sophistication in which Cécile and Raymond. She arrives, at the drunken and now-forgotten invitation of Raymond, as father and daughter vacation at their summer villa on France's sun-drenched southern coast along with Elsa (Mylène Demongeot), Raymond's latest young, pretty, frivolous fling, who seems to have been chosen as much to provide an amusing playmate for Cécile as for more grown-up playtime with her father. Cécile, a failed student who seems literally adrift on those cerulean-blue Mediterranean waters, wants her and her father's pleasure-seeking to go on forever, not weighed down by the pragmatism of someone like Anne, whom Cécile is initially fond of as long as she's just one of the rotating crowd of her father's lovers, but who treats Cécile like a mother from the beginning and only gets more oppressively concerned for the aimless young woman's moral and intellectual well-being as Raymond seems to become, to Cécile's shock and dismay, actually committed to this sensible lady.

Further complicating Cécile's feeling that it's just her and her father against the world is an intense sexual awakening that comes in the form of Philippe (Geoffrey Horne, The Bridge on the River Kwai), a slightly older, perpetually skimpy-trunks-clad, bronzed Adonis vacationing with his family nearby. It's as much because Anne puts the kibosh on these two bathing beauties' headlong rush toward consummating their urges (in a boiling-point-erotic scene that, before Anne's interruption, must have caused gapemouthed frissons in 1958; even today, a cold shower might be in order) as it is due to her disruption of the perfect, codependent insularity of her and her father's relationship that Cécile decides to get rid of Anne, hatching a plan with the spurned Elsa and the reluctant Philippe to arouse Raymond's jealousy and make him desire Elsa once again, Cécile correctly predicting that his midlife-crisis male ego needs more stroking than Anne's deep, vulnerable commitment can provide. The extremely unhappy result of Cécile's machinations rends the veil that has hidden most of life's real feelings and consequences from her in the quasi-sophisticated indolence her father has recklessly allowed.

Most of the film is told in flashback to "that summer," a bittersweet memory captured in achingly bright Technicolor by the superlative cinematographer Georges Périnal (who had worked with Kerr before as DP on the color The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and also proven his black-and-white mettle on Carol Reed's The Fallen Idol). The color sections, in their pictorial sensuality, are well-suited to the warm water and sand setting and the sexually fraught aura between all the characters (even, disturbingly though never at all explicitly, between Raymond and Cécile), while the present from which we're flashing back is in a subdued black and white that shimmers with an also beautiful but much cooler light, reflecting the probably eternal damper that the events of the prior summer have had on Cécile's authentic frivolousness, effectively ending her youth and preparing her for the false-gaiety, disconnected adulthood to which someone of her station and temperament must eventually resign herself. As Raymond, Niven is all over-tanned, muscular, vain-aristocrat health and flirtation, a perfect "fun dad," and Kerr is a just-right mixture of softness and stiff-upper-lipped Englishness makes for a most sympathetic Anne. But the show is inevitably stolen by Seberg, most particularly in a final scene in which the entire meaning of the film's story plays out, in just a few intense, breathtaking moments, on her visage. With its shallow-focus, near-extreme close-up foregrounding of Seberg's inconsolably sad face, her pristinely beautiful features twisting under realization and regret, this conclusion is a devastating moment of revelation that's one for the cinema-history books; it never leaves you.

Bonjour Tristesse's biggest potential problem is Seberg's elocution as she voiceover narrates in the present, meditating upon that summer and how it changed her; the recitative quality of it jars at first, and seems not to be in keeping with the bubbly, snappy, throwaway delivery of much of Cécile's other dialogue. But as the story unfolds and we begin to see where it's going, the stateliness of the narration seems much more apt; Cécile's carelessness and naiveté have gone by now, were in many ways merely a front to begin with. By the film's shattering end, these moments of inner dialogue have taken on a soliloquy-like gravity. The Technicolor vividness of the Riviera scenes themselves takes on a strangely melancholy quality, too, as the story progresses and these lusciously envisioned memories contrast ever more sharply with the film's grounded, black-and-white present. There are few real close-ups in the film, with most of the action taking place in visually arousing but calmly composed medium and long shots that make the characters seem blissfully, unworriedly integrated into their sea-and-sun surroundings, so we're free to regard and become involved in what unfolds between them from a certain distance. That Raymond and, especially, Cécile have experienced their lives and loves from that same distance is driven home beautifully by that narratively and emotionally climactic final shot; rarely has the meaning of everything that's come before been so transfigured by a single concluding image.

Of course, it's not just the monumental, iconic ending that uses the language of cinema brilliantly; that's just the cherry on the decadent romance-and-emotion sundae Preminger serves up. From the exquisite Saul Bass-created titles, to Georges Auric's (The Wages of Fear, Lola Montès) score that turns on a dime from frolicsome to swooningly romantic, to the appearance of Jean-Paul Sartre's favorite chanteuse Juliette Gréco's intoning of the film's title tune as the Proustian trigger that sets Cécile's ennui-soaked memories flowing, to Preminger and Périnal's visual mastery in using their camera to render both the elaborately beautiful coastal landscape of the Riviera and the simple, distinctive, youthful beauty of Seberg's face as wordless touchstones, evocations of states of mind, Bonjour Tristesse is a lush treat that captivates the imagination and the emotions through its steadily building, graceful, often visually indulgent storytelling. The end result of all that luxuriant beauty is much more than just a pretty-looking bauble, however: Like his fellow émigré Douglas Sirk, Preminger knows that heightened, alluring artifice (such as that achieved with the nearly graphically-designed feel of Périnal's color photography) has a troubling sense of unreality built right into it, and if you exaggerate it enough, you effectively hint at some niggling omission, some underlying truth that's being evaded; Cécile's and the film's sad ultimate confrontation with a reality much harsher than Technicolor are ultimately one and the same. In the sense of handing us the fizziest, fullest glass of cinematic champagne and having us gulp it down eagerly, all the way to its unexpectedly deep, bitter dregs, Bonjour Tristesse is an intoxicating film, one that gives you the entire experience of being drunk on pleasure, freedom, and love -- up to and including the preordained hangover.

THE BLU-RAY DISC:

An AVC/MPEG-4, 1080/24p transfer presents the film at its original Cinemascope aspect ratio of 2.35:1, and it's a remarkably fine job, picture-quality wise. Only the barest hint of print wear or flicker is noticeable anywhere; otherwise, the Technicolor vividness and elegant black and white of DP Georges Périnal's cinematography are practically perfect, the colors rich and vibrant (absolutely none of that dreaded yellowishness of uncared-for Technicolor), the blacks and whites beautifully contrasting, balanced, and solid. (In fact, the black and white sections are so clean-looking, I was suspicious that digital noise reduction (DNR) had been overused; however, it appears that black-and-white 'scope cinematographic processes can result in significantly finer grain than otherwise*, while the color segments look very film-like indeed, so it can be said that very healthy, un-manipulated celluloid texture is present and stunning throughout.)

*Much gratitude to Alexander Peacock and Brian Rose for their helpful technical knowledge and insights on the matter.

Sound:The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 score conveys the film's original mono sound wonderfully well, with all dialogue crisp and clear, and all music (Georges Auric's lush score, the title tune performed by Juliette Gréco) rich and full. There's no distortion, imbalance, or other audio flaws to report; it sounds pristine from start to finish.

Extras:--The film's intriguing curio of an original theatrical trailer, which starts off as an amusingly awkward, very stage-y, and obviously re-edited "interview" between an avuncular American and a rather unhappy-looking Françoise Sagan, before segueing into some snips of the film and its Saul Bass-designed credits.

--An isolated score track in DTS HD-MA 2.0 surround.

--A slim but pretty booklet featuring photos from the film and its shoot (many featuring Preminger) and a very well-written, admiring essay by film historian Julie Kirgo.

An emblem of bittersweet (heavy on the bitter) adolescent fatalism, Otto Preminger's Bonjour, Tristesse, like the French novel it's based upon, cuts deeper and lingers longer than its teen-centricity might imply. With the half-pixie, half-demon, gorgeous but slightly awkward Jean Seberg in the central role of Cécile, the character's young-adult vulnerability and indecisiveness ring out loudly from behind her front of cosmopolitan wit and sexual precocity; her childlike clinging to her even more childlike, wealthy-womanizer father, and his reciprocal reliance upon her, make them the only two solid human presences in each other's luxe, dissipated, overprivileged lives, in which they pass the year in a well-appointed Paris flat and play and flirt on the Riviera during the summers. It's one of these summers that's recounted over the film, in blazing-Technicolor flashbacks from the present-day black and white -- the summer of Cécile's sexual and emotional maturation at the hands of a beautiful young man and the tragedy (aided by Cécile's precocious machinations) that befalls her father's utterly incongruous engagement to a pragmatic, substantial woman (Deborah Kerr) whose depth is utterly foreign to these sparkling but empty jet-setters. Bonjour Tristesse is a blatantly, beautifully melodramatic work, Preminger's deep understanding of the source novel expressing itself through a complementary, layered, and resonant stylistic astuteness, from his Wizard of Oz-like use of color contrasting with black and white (conveying the force of emotional gravity on even these affluent, free-floating summertime sexual and emotional adventurers, who are no exception to the changing of the seasons or the what-goes-up-must-come-down rule) to his choice of the luminous but not quite fully formed Seberg as the lost little girl who puts on a brave, worldly front. It's an enchanting, sensuous picture that bathes us in the physical eroticism of the warm summertime Mediterranean beach in blazing-hot Technicolor before dousing that fire with the cool, imperviously pretty black-and-white reality of here-and-now Paris. The film earns every bit of its teenaged angst and ennui; it neither excuses nor condemns its characters for their dangerous blind spots and self-indulgences, instead exploring their confrontations with the eternally sad elusiveness of true freedom and real love, the painful discovery of which divides the open-hearted, un-self-conscious, literally careless kids from the cautious grownups, no matter their actual ages (it's Cécile who grows up, not her father). The title, which translates as "hello, sadness," seems less and less flippantly ironic with each passing minute of Cécile's story; as she learns, and as we realize soberly along with her, it's the greeting that her once-unfettered, carefree childlikeness is giving to her impending, desolate-looking adulthood, in which clever words, happy faces, and insouciant detachment will be nothing but obligatory masks donned to hide an unbearably heavy heart. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||