| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

For Ever Mozart

The Movie:

The Cohen Media Group just released two excellent Blu-rays of films directed by Jean-Luc Godard. One of them is 1985's Hail Mary, a controversial riff on Catholic dogma released during what film writers of the time characterized as Godard's comeback streak, after years in the Maoist wilderness. The other is 1996's For Ever Mozart, an often subdued and fragmented rumination on war and cinema that is oddly marginalized within Godard's eclectic filmography despite echoing concerns from his earliest work and anticipating the mood and style of his most recent work.

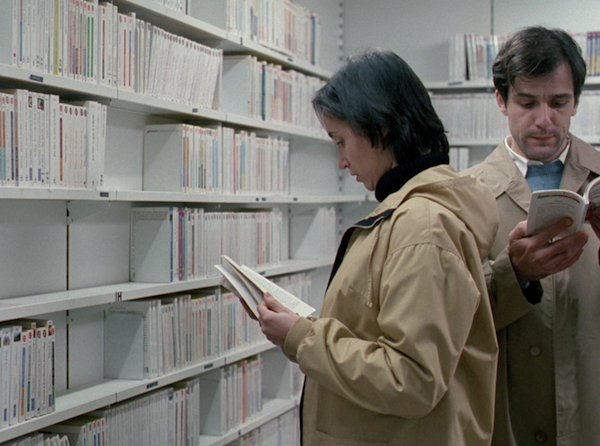

Godard has often criticized ongoing warfare in his films, the conflicts in Algeria and Vietnam most famously. For Ever Mozart is his reaction to the Bosnian War of the '90s, though refracted through a story from the French paper Le Monde about Susan Sontag putting on a production of Waiting For Godot in Sarajevo, where the French journalist criticized Sontag and suggested she should have put on a Marivaux comedy instead. Godard has his lead character Camille (Madeleine Assas), a philosophy professor, read the article and decide to do just that. However, in this era before the ubiquitous use of Amazon.com, Camille is unable to find Marivaux at her local bookshop and instead settles on a play by Alfred de Musset, One Does Not Trifle With Love.

In the first section of the film, Camille heads out with her cousin (Frédéric Pierrot), her parents' maid (Ghalia Lacroix, who recently co-wrote Blue Is The Warmest Color), and her washed-up filmmaker dad (Vicky Messica) to Sarajevo. While the goal of doing the play in a war zone seems idealistic and foolish from the get-go, Godard does not necessarily seem to ridicule the characters' impulse to put on this production. As in much of his later work, Godard's attitude seems melancholy and world-weary, like he wishes they could get away with this act but knows all too well what happens to idealists.

This section, like most of the film (and, frankly, most of Godard's later work), does not have much of a dramatic engine. Instead, the characters mostly sit around, speaking in quotes and aphorisms, teasing out philosophical ideas. Godard plays with the soundtrack, overlapping dialogue from different settings and starting and stopping music as abruptly as pushing a button. He often locks his camera down and allows the scenes to occur within and without the frame-line, disrupting our expectation that the camera will inevitably follow or cut to the important actions within a scene. It is jarring, and Godard seems most interested in creating a rhythm of speech and images, a collage of impressions. First-time viewers are suggested to not be too uptight about plot or realistic characterization, and to appreciate Godard's unusual craftsmanship. (If you feel like decrypting Godard's numerous layers of references, additional viewing and a few trips to the library will probably be necessary.)

The second section is easily the most dramatic of the film. Having already been ditched by her filmmaker dad, who hitched a ride back to France at a truck stop, Camille and her collaborators are captured by Serbian soldiers. They are interrogated, tortured, and raped. Mortars explode and machine guns are fired at prisoners. The Red Cross comes to check on the captives, and they are denied access. Godard fragments the action even more intensely at this point, often depriving the audience of the usual catharsis (and voyeuristic charge) of letting the audience stare at the atrocities head-on. Often there will be sounds of gunfire or isolated screams punctuating scenes, without us being able to pinpoint where they're coming from. Also, Godard juxtaposes moments of egregious violence with bursts of absurd humor, like a moment where a soldier grumpily confiscates a prisoner's boombox because he doesn't like the song playing.

The third section brings us back to the washed-up filmmaker, dressed up a bit like Godard and potentially intended as a self-deprecating caricature. The director is shown filming a seaside scene from an idiotic script called The Fatal Bolero. At one point, we see him directing a would-be ingenue (Bérangère Allaux) to say the line, "Oui." ("Yes.") Off-camera, he replies, "Non." ("No.") And so they do another take. And they do another and another until the actress gives up and lies down on the sand. Is the filmmaker searching for a poetry he can't find in the performance? Is he rejecting the scene? Is he rejecting this whole mode of filmmaking? Presented, as it is, directly after the brutal and absurd section with the soldiers and prisoners, this passage seems to represent Godard's assertion that cinema has failed to reach its potential as a tool for revealing, reporting, and reflecting the state of the world. The filmmaker character is hamstrung by producers to create a banal distraction while his daughter is being tortured a few thousand miles away. When The Fatal Bolero is released and it turns out to have a bit of art to it (and no nudity), the audience rejects it in favor of a new Terminator movie. Of course, Godard is a bit of a grouchy old man when it comes to modern movies (there is a similar gag about the popularity of The Matrix in Éloge de l'Amour), but his passion for cinema as art makes For Ever Mozart appealing and makes it much more than an illustrated lecture.

The final brief section of the film is set at a Mozart concert. Why? Maybe there is something in the biography of Mozart that speaks to the plight of the artist trying to transcend his times. Or maybe because the continued commercialization of Mozart shows the way that modern culture trivializes art and commodifies it. Or maybe because Godard just needed an ending and is a mischievous bastard who decided to conclude his film on -- and name his film after -- a non sequitur just to keep us all guessing.

While not for beginners, For Ever Mozart is definitely not Godard at his most opaque. Portions still might test the patience of even the most ardent art-film lover, but taken as a whole, it is a satisfying teaser of the more essayistic films Godard would go on to make in the twenty-first century.

The Blu-ray

The Video:

The 1080p AVC-encoded pillarboxed 1.37:1 image boasts an impressive amount of clarity. There are SD clips from the film included in some of the bonus features, and the difference in detail is like night and day. Sometimes the image can be a little soft and grainy, but that seems to be a product of the film source and not the transfer. The color palette is on the muted side, with occasional bursts of deep red and blue.

The Audio:

The movie is offered in LPCM 2.0 French with optional English subtitles.

Certain brief passages of the film are untranslated, often because they are in a language other than French. However some of these passages are in French. James Quandt acknowledges this lack of translation in his audio commentary (see below), so it would seem to be some sort of artistic choice -- either to get the viewer to just accept the dialogue as rhythmic sound whose content isn't vital or to get us to brush up on our high school French vocabulary.

Otherwise, the sound is excellent. The complex layered soundtrack created by Godard and his sound man François Musy comes through clearly. Dialogue overlaps, music comes in and out, bombs explode and guns are fired, and it all weaves into a brilliant, crisp sound tapestry.

Special Features:

There are a number of worthwhile supplements for For Ever Mozart. Enclosed with the disc is a great booklet with photos and two absolutely vital written pieces: Fergus Daly's essay on For Ever Mozart, "A Beautiful Exception," and a 1994 interview with Godard conducted by filmmaker Hal Hartley, called "In Images We Trust."

- Audio commentary by film critic James Quandt - If you find yourself watching For Ever Mozart wishing that it somehow came with footnotes, then this is the commentary for you. Quandt very helpfully pinpoints the literary and philosophical references that are all over the film, successfully enriching the viewing experience. Admittedly, it can be a little dry -- Quandt sounds like he is reading all of his comments -- and there are silent gaps here and there, but the information is so cogent and illuminating that the track is well worth it.

- JLG/JCS (23:01) - There are four interview featurettes included on the disc; two of them relate directly to For Ever Mozart and two of them relate more generally to Godard's work. This first interview is with Jean-Claude Sussfeld, who was the second assistant director on La Chinoise, and so it is related to his experiences working with Godard on that 1967 film. Sussfeld's impressions of JLG reveal a serious, scholarly, and sometimes shy man. One interesting anecdote involves Sussfeld accidentally totalling a car that Fiat had lent to be in the movie. Another involves Sussfeld and Godard getting on a Parisian tour bus, pretending to be foreign and speaking a language they made up.

- JLG/FM (15:30) - This next interview is with François Musy, Godard's sound man since the early '80s. Musy talks about how Godard thinks of the soundtrack at every stage of the filmmaking, including the writing and shooting. Musy reveals that many of the overlapping sounds that end up in the final film are played on set for the actors to react to and perform with. It's a fascinating look into their decades-long collaboration, illustrated with examples from this film.

- JLG/WK (19:48) - Willy Kurant was the cinematographer on Godard's 1966 film Masculin Feminin, in a rare instance in Godard's '60s work where he didn't work with New Wave legend Raoul Coutard. Kurant talks about the difficulty of stepping into Coutard's shoes behind the camera. He talks about the atmosphere of the French film scene at the time, and obliquely refers to difficulties that he and Godard had working together. It's an interesting interview, but like the Sussfeld piece, it's a little puzzling why exactly it was included on this release.

- JLG/ADB (10:45) - Godard biographer Antoine de Baecque offers some details about the context and history of the making of For Ever Mozart. Some of it is redundant with the information that James Quandt provides in his commentary, but that is inevitable. Like all the interviews, a worthwhile watch if you're interested in Godard's filmmaking methods.

- 2013 Re-Release Trailer and a handful of trailers for coming Cohen Film Collection attractions when you pop in the disc.

Final Thoughts:

I first saw For Ever Mozart in high school, when it first hit VHS. My best friend and I rented it. Neither of us are dummies, but nonetheless we both fell asleep sporadically throughout the film. These days, I have no such drowsiness issues. I find the film provocative and fascinatingly constructed. Point is, while it's obviously not for all tastes, if you're adventurous or patient or curious or... let's face it... pretentious, For Ever Mozart comes Recommended.

Justin Remer is a frequent wearer of beards. His new album of experimental ambient music, Joyce, is available on Bandcamp, Spotify, Apple, and wherever else fine music is enjoyed. He directed a folk-rock documentary called Making Lovers & Dollars, which is now streaming. He also can found be found online reading short stories and rambling about pop music.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||