| Reviews & Columns |

|

Reviews DVD TV on DVD Blu-ray 4K UHD International DVDs In Theaters Reviews by Studio Video Games Features Collector Series DVDs Easter Egg Database Interviews DVD Talk Radio Feature Articles Columns Anime Talk DVD Savant Horror DVDs The M.O.D. Squad Art House HD Talk Silent DVD

|

DVD Talk Forum |

|

|

| Resources |

|

DVD Price Search Customer Service #'s RCE Info Links |

|

Columns

|

|

|

Night Across the Street

"He was soon to have done with calendared time, and it had already ceased to count for him. He sat in the middle of his own consciousness; none of his former states of mind were lost or outgrown. They were all within reach of his hand…." - Willa Cather, Death Comes for the Archbishop

It's almost impossible not to project an important, "Final Statement" status onto the late Raul Ruiz's fantastic film Night Across the Street, but it's also pointless to avoid thinking of it in those terms, treating it as the movie that just happened to be the last rich deposit into Ruiz's long, hugely varied, bursting filmography of over 100 films spanning five decades. Not only did the ailing director himself (who died in 2011 not long after finishing it) make it well known that he envisioned this picture as his very last work, embracing the idea that it would be released posthumously, but it's so self-consciously about not only death (though it's very much about that, too) but endings in every sense (of stories, of lives), and the tantalizing, terrifying, unanswerable question of their finality: How tidily circumscribed, finally, is the life (remembered, lived, or ended) of, say, you, or me, or a famous long-dead composer, or a film director, or a fictional character? Its concerns are heady, but Ruiz has long since proven he's up to it: Very much as in his last film, the superlative Mysteries of Lisbon (adapted from a 19th-century Portuguese novel, whereas Night Across the Street takes some mid-20th-century stories by Ruiz's fellow Chilean Hernán del Solar as its jumping-off point), Ruiz isn't shy about getting metaphysical, but form and content are made to reflect off of and escalate each other, the philosophical and the emotional merging in a way that's positively ebullient, riveting, never dry or ponderous: The film seduces us from start to finish with the dizzying, gently discombobulating sense that we're watching stories inside of stories inside of other stories, nested like uniquely unpredictable Russian dolls, keeping us on our feet and never entirely sure how big or small the whole will get, or how one part will resemble or connect to the others.

Our gateway into and guide through Night Across the Street's labyrinth of story-spaces -- memories, fantasies, sensuously touched beads from many diverse periods and forms of literature, drama, music, and film -- is the very fecund and expansive mind of Don Celso Barra (Sergio Hernández, No), an elderly, single, deskbound functionary in a Chilean port town whose impending retirement from his paper-pushing position in an amiable, cozy, dull little office has him preoccupied with his own mortality, toting around an old alarm clock to remind him of when to take his medicine and living on several planes -- his humdrum life at the office and in a tiny rented room where he makes ships in bottles, his actual memories from childhood, and his "memories" taken from cultural figures and productions -- at once. The melange of past, present, reality, and fantasy in which Don Celso's conviction that he's soon to die (whether by his own hand or someone else's) allows a privileged existence makes for a movie experience virtually boundless in its intrigues and delights: Celso as a boy has a face-to-face chat with Robert Louis Stevenson's Long John Silver, whose pirate ship young Celso saw in a movie (of which Ruiz lovingly cuts to the relevant few frames of aged black and white celluloid), probably at the same cinema to which he takes another childhood conversation partner, none other than Ludwig van Beethoven himself, to show the composer a modern wonder. Meanwhile, the man the boy grew up to be (whom we see, in what could conceivably be the film's only scenes that are supposed to "really" have happened, verbally spinning these likely embellished memories and tales from behind a dusty microphone for a radio audience in a world still without TV, Don Celso's "present" appearing to occur in the late 1940s or early 1950s, though time is utterly indeterminate here) strikes up a friendship with the real-life French novelist Jean Giono (Christian Vadim), an intellectual and Spanish Civil War veteran who once wrote that he would move to Don Celso's Chilean burg of Antofagasta because he loved its name, but never actually set foot there (he thus belongs, for the film's purposes, in the same category as Long John Silver or Beethoven). The old man and this version of the French novelist go on long walks together, discuss philosophical matters, and play dominoes, Don Celso revealing his own calling as a creator of fiction, a storyteller as well as a character, by imagining a pulp-fiction plot involving his landlady and fellow boardinghouse residents in which a love triangle, an old man's hidden life savings, jealousy, and robbery will lead to murder, possibly Don Celso's own. That story plays out onscreen at the same time Don Celso's bureaucratic-oddball fellow office workers are preparing to celebrate their harmless old colleague's retirement, Don Celso continuing to make his bottled pirate ships and relive in vivid detail the joys and terrors of teenage French class even as the sinister intrigues of the juicy B-film noir weave in and out of his superficially humdrum but actually wildly imaginative existence.

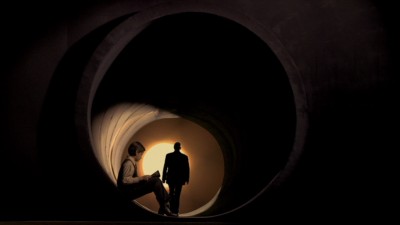

It's in the film's opening scenes, set in that French class of uniformed schoolboys amid which the old Don Celso with his alarm clock looks very incongruous indeed, where the iceberg-tip of its prodigious and plentiful literary/cultural references first blossoms forth: Proust (quoted in the very first line of dialogue we hear) and Mallarmé are in Night Across the Street's already-heady mix, too (in 1999, Ruiz accomplished the impossible by adapting Proust's Time Regained into a marvelous film), along with Giono and Stevenson and Beethoven and Hernán del Solar and who knows what else, but our familiarity with these references' sources matters little in the end, as Ruiz offers them up not for our instruction but for our delectation, the way they interact with and enhance the film's theme of the interplay between literature(s) and lives. One needn't be directly familiar with Proust's utopian, memory-undamming madeleine to reap the benefits of Ruiz's faith in the same principle expressed through this film: Here, the arbitrary but deeply magical talisman is not the particular taste of a tea-biscuit on the tongue but the word "rhododendron," a play on a nickname Don Celso had as a child, and a word which allows him (and us) to be swept away and buoyed by the flood of real and imagined memories and stories cascading over the screen, a flow of potentially unlimited associations that suggests endless connections, endless discoveries, endless life. That's not to suggest that Ruiz doesn't have a very firm structure in place, though, however elliptical and dreamlike it feels. By the time we reach the film's concluding passage, where we find the young and old Don Celsos actually entering the barrel of the gun that has killed him (shades of the suddenly miniaturized human figures in Mulholland Drive, David Lynch being a spiritual brother of Ruiz's, with his stories similarly traversable via secret passages and strange/fanciful but tightly soldered connections), and then witness the peculiarly comforting events that occur when they emerge from the other end, it seems the right, inevitable conclusion, the culmination of what only seemed to be "random" associations, imaginings, and remembrances of things past.

To conjure in the most vivid manner the film's various planes -- Don Celso, the past, the future, life, literature, and history -- freely commingling with each other, Ruiz finds jaw-droppingly effective ways of visualizing overlaps of different times, places, and realities. Exteriors -- the young Celso's fiery-orange-hued interactions on the beach with Long John Silver; the strolls taken with Jean Giono; an exquisite walk-and-talk that tracks with Don Celso and his interlocutor in profile and moves smoothly past a 19th-century mural on a municipal wall to open onto the modern, gentrifying Antofagasta of today -- are shot in some sort of rear-projection or green-screen process that, perfectly, places the human figures both within and apart from their environments. Interiors are lit and composed by Ruiz and director of photography Inti Briones (whose different but equally ravishing work was on display in Julia Loktev's The Loneliest Planet) into artificial spaces of suspended time, a limbo in which clashing registers of realism can feasibly play out superimposed on one another; the elegant, evenly-paced lateral pans that take us through this unpredictable, unstable, minutely and evocatively detailed mise-en-scène and the rich symmetries of the deep-focus compositions are nothing short of divine to experience, and they imprint the conjunction of far-separated spaces and times in which Don Celso has come to exist in a way that makes his nebulous twilight reality undeniable and unshakeable.

The film would be a touchstone, a wellspring of emotion to make us reel admiringly whether or not we knew it was the last testament of such a serious, bold, and accomplished artist, but the fact that it is makes it that much more poignant. For one more example of life's not being fair, there is no rule guaranteeing us that even the greatest cinéaste's last work will be the kind of precious, life-giving creation that Night Across the Street celebrates (think of how unfortunate it is that Antonioni ended on the deeply flawed Beyond the Clouds), but happily, it just so happens that Ruiz, stepping behind the camera for the final time, was able to add one last jewel to the tip-top crown of his best work. He's given us a film that manages to become just what it pays homage to -- a stirring, infectious, transcendent reminder of how essential are the effects and results of imagination and artistic creation, how they can so welcomely and edifyingly wend their way through what we think of as our ordinary, "real" lives, quietly and humanizingly becoming a part of us that is, in its own way, just as present, just as real.

Video:

This transfer of the film from Cinema Guild is, typically for them, very good; the stunning use of high-def digital video's rightly vaunted properties by Ruiz and DP Inti Briones -- "cinematic" qualities that approximate film in some ways with sharpness and responsiveness to light, in addition to DV super-clarity -- is done almost entirely full justice here, with all of the film's colors and skin tones and the solidity of darker scenes making the transition unscathed, and only a little bit of occasional edge enhancement/haloing in the way of compression artifacts. It's a splendid-looking film delivered equally splendidly by its conscientious North American distributors/caretakers.

Sound:The disc's Dolby Digital 2.0 track (which, on my system, set to PL-IIC, worked often as a surround track, particularly for the music), is rich, clear, and multifaceted, fully bringing home the film's full range of layers and spaces, from very intimate (a great many dialogue scenes) to expansive (the aforementioned music, exteriors with background/ambient sound), with no imbalance or distortion noted at any point.

Ballet aquatique (54 min.), an experimental film-essay by Ruiz, completed before he began Night Across the Street, that combines elements of documentary, surrealism, and critique to pay explicit homage to Jean Painlevé, that intrepid French maker of eternally fascinating, inventive up-close cinematic documents of sea life. In addition to much footage from Painlevé's work, Ruiz himself appears here, alongside actor Melvil Poupaud (A Christmas Tale) and Night Across the Street's French producer François Margolin, for a commentary on Painlevé's subjects and art-making that's as deeply admiring as it is affectionately irreverent.

--"Lasting Elements on the Last Horizon" (10 min.), a video essay on Night Across the Street by critic Kevin B. Lee that, like the similar piece he did for Cinema Guild's release of The Day He Arrives, is an enraptured but highly articulate expression of a remarkably sensitive, finely attuned response to the filmmaker's vision.

--An insert booklet featuring an essay by critic/curator James Quandt (a writer frankly much more worthy and capable than I of addressing Ruiz's film(s) and style; it's an impassioned, insightful, and informative piece).

--The film's theatrical trailer along with previews for several other always-worthy Cinema Guild titles like Neighboring Sounds and The Turin Horse.

The warmly complex, melancholy, at times spryly funny currents of Night Across the Street, the late Chilean director Raul Ruiz's final masterpiece, make it inviting -- languidly, bottomlessly touching and pleasurable -- despite its wholly unpredictable narrative puzzles. Ruiz intended this picture to be his swan song, and as it takes us on a long walk through a lifetime's worth of an eccentric, lonely, soon to be retired Chilean office clerk's (Sergio Hernandez) memories and fantasies, its surprisingly effusive, trenchant yet playfully rendered modernist consideration of stories, storytelling, art, and life -- and the mysterious, sobering way these things are bound up with the passing of time and death -- takes on a very tender, elegiac tone. The film doesn't do anything as tidy as recap or sum up Ruiz's tremendously diverse body of work, but what makes its themes and its patiently laid-out obsessions seem so very fitting for a last film is its truly grand, acute homage to the power of art -- music, novels, poetry, film -- even as it insouciantly stays true to the modernist spirit by painstakingly acknowledging all the vagaries and juicy lacunae in fiction and drama and their strange, ceaseless back-and-forth with "real" life (or is it? The film ultimately, wonderfully suggests that each one of our urgent, all-consuming life stories is ultimately but an annex to an ever-expanding mansion of scenarios, all simultaneously accessible in some sort of afterlife that equalizes us and all the characters, whether they actually lived or imaginary, that have ever been). This is a cerebral, reflective, restlessly self-conscious film, but radiantly so: It positively glows with the pleasures of what it has to impart, the deep-down, blessed feeling that a few bars of music, a story fragment, a quotation, or even some random, trivial occurrence or object can be enough to transport us to a state of grace. Thus affirming art and life in equal measure by skillfully enfolding the one into the other, Night Across the Street is a posthumous gift, a perfect key for unlocking not only Ruiz's decades-spanning treasure trove of a filmography but the entire, chaotically overflowing storehouse of culture and creation that, in Ruiz's insistent, accepting view, goes some true, real way toward compensating for inevitable mortality. Highly Recommended.

|

| Popular Reviews |

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Sponsored Links |

|

|

| Release List | Reviews | Shop | Newsletter | Forum | DVD Giveaways | Blu-Ray | Advertise |

|

Copyright 2024 DVDTalk.com All Rights Reserved. Legal Info, Privacy Policy, Terms of Use,

Manage Preferences,

Your Privacy Choices | |||||||